New York City is a city of innovation, of wealth and poverty, of great public spaces and of great social needs. The cityscape is shaped by the pressures and challenges of city life. It’s no surprise that the city’s response to the shocking damage wrought by Hurricane Sandy, and the reality of future sea level rise, includes world class projects for storm protection. Here are the central projects under discussion.

Rebuild by Design is an initiative spearheaded by The United States Department of Urban Housing and Development (HUD). This project is an on-going search for policy-based solutions for protecting vulnerable coastal cities.

Seaport City is a multipurpose levee design for the Lower East Side of Manhattan that appeared when the City released the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency (SIRR) report in June, 2013.

As the more extensive set of plans, we’ll look at Rebuild by Design first.

The multi-stage design competition began with a pool of 148 entrants in June, 2013, narrowed to ten teams that August, and this June six finalists, with fully developed plans slated for construction, were named.

Advisors to the Rebuild competition include William Solecki, director of the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities and science advisor to City Atlas, and Klaus Jacob, whom we interviewed here.

In the yearlong development process, the Rebuild teams designed proposals for increased protection against storms like Sandy in the regions of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Teams consisted of multi-national and multi-disciplinary groups; engineers, world leading architecture firms, community planners, and scientists from institutions including Rutgers University and the Urban Ecology and Design Laboratory at Yale.

Among the designers involved, Claire Weisz of the WXY/West 8 team, and Diana Balmori of the OMA team (a finalist), have prior interviews in City Atlas.

International participants include One Architecture, a Dutch firm, which collaborated with the team led by Bjark Ingels Group (BIG), a fast rising firm based in Denmark with several large projects underway in New York. One Architecture also has international work that includes revitalizing a 1950s monastery into a state-of-the-art health center, and a development plan for turning Les Halles, Paris’s traditional central market, into a green and efficient park and shopping center.

The world-class talent assembled, a virtual “Dream Team” of designers and engineers, might seem to risk a highly publicized initiative disconnected with local impact. But each team conducted deep, careful, research into the needs of the local community, and into the larger environmental context of the challenge. The study that went into developing the projects remains accessible in the research pages of the Rebuild site.

The Rebuild research begins with this gripping paragraph:

On October 22, 2012, a tropical wave formed in the Caribbean Sea and quickly grew into a tropical storm with frightening potential. It was the hottest year in recorded human history, and the sea water was unusually warm. Strong winds whipped the wet Caribbean air into a frenzy as the storm moved North and West, and on October 24 the system had become a hurricane. Meteorologists named it Sandy, and predicted it would sweep through the Caribbean islands and make landfall somewhere on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States. When it did, Sandy turned out to be more dangerous than anyone initially anticipated. The “Superstorm” intensified and grew as it moved across the Caribbean, ultimately covering an area more than one thousand miles in diameter, making it one of the largest hurricanes in U.S. history. Its winds were both punishingly severe and painfully slow, and the steady, relentless tempest seemed to pause whenever possible, as if it aimed to inflict damage on nearly everything in its path.

With the experience of Sandy as a starting place, the competing team members met with experts to learn about the local businesses and environments their coastal solutions would protect. The Municipal Art Society, as a lead partner, helped guide the Rebuild teams in outreach to New Yorkers. Residents and business owners were given the opportunity to directly voice their opinions to the teams through community workshops and public events.

As an example of how the designers learned from local organizations, the project borders of one group, Big U, extend under the jurisdiction of the Battery Conservancy. The Conservancy was able to work with the design team to determine the best ways the design could suit the various regions of Lower Manhattan and the organizations at risk for flooding. The community responded positively to the Big U proposal, believing that the designers took into account the concerns of the residents. Rebuild also created programs like “’Scale it Up,” which sought to better explain the design concepts to local audiences.

Rebuild by Design’s mission is less about basic storm protection, and more about creating multi-purpose infrastructure that provides yearlong community benefits. For example, one project proposal, named Living Breakwaters by its SCAPE/ Landscape architecture team, is for a system of breakwaters strategically placed along the South Shore of Staten Island. These would protect local communities, while providing certain area parks with beneficial flooding. The proposal also highlights a community education center that would tie residents with local marine life and sustainability.

In April 2014, the teams presented their projects online and to attendees in New York and New Jersey, with each project forwarded to HUD, who made the final call. In June, six finalists were chosen. Of the winning projects, two are oriented towards protecting New Jersey residents from future flooding, with the remaining winners focusing their efforts on Long Island and the New York City area. The projects divide a total of $920 million in HUD funding as follows:

- Manhattan: BIG U, a 10 mile protective system around Lower Manhattan that includes a berm — a raised bank to protect against storm surge—and new park expansions and routes to enhance outdoor life in the area. $335 million of funding.

- Long Island: Living with the Bay, a comprehensive plan for strengthening storm barriers that includes added marshlands and small streams in communities designed to drain flooded tributaries in Southern Nassau County. $125 million.

- The Meadowlands, New Jersey: The New Meadowlands, a marshland restoration project that includes the creation of a publicly accessible Meadow Park, added berms, recreational improvements, and a public access point called the Meadow Band. $150 million.

- Hoboken, New Jersey: Resist, Delay, Store, Discharge, a project designed to build up both natural and artificial infrastructure to deal with flood prevention and flood drainage. The proposal includes installing pumps and creating drainage routes, infrastructure to slow the speed of runoff, and a “soft landscape for coastal defense.” $230 million.

- The Bronx: Hunts Point Lifelines, a system designed to protect a major regional food supply hub that includes education for communities to create their flood and storm infrastructure, emergency supply lines for coastal traffic, and Cleanways that “re-center the neighborhood around transit and connect it to the waterfront greenway. New infrastructure improves air and water quality, provides safe passage for pedestrians through truck routes, and increases local access to food.” $20 million.

- Staten Island: The Living Breakwaters project, a chain of breakwaters along Staten Island’s South Shore that seeks to both prevent storm inundation and foster increasing biodiversity in the calmer water pockets. There is also an initiative in place to create educational community facilities focused around these new areas, from kayaking to bird watching stations. $60 million.

Despite being funded largely by HUD’s CDBG Disaster Recovery program, Rebuild appears set on supporting proposals that do more than keep out storm water. And while some of the designs are idealistic, they all have a real-world timeline, and budget. Team BIG U claims the largest piece of the pie for phase one of construction, approximately $335 million. As quoted in Gothamist, Mayor De Blasio expects construction to begin on the six New York projects within “four or five years.”

Are these sometimes elaborate—and most definitely expensive—projects what flood-prone areas actually need? The winners all boast sustainable proposals that will offer an increase in public amenities, with these features being the most prominently advertised aspects of the publicly viewable proposals. Could the designers be adding unnecessary or even unwanted features to their projects?

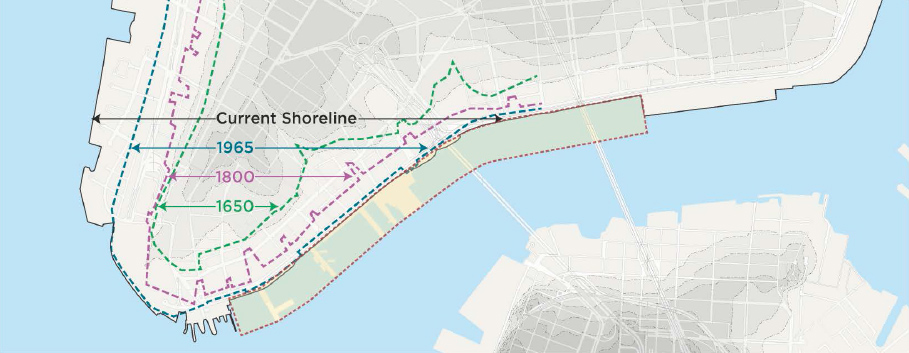

Preceding the Rebuild by Design competition, Seaport City came out as part of the City’s SIRR report, in June, 2013. Seaport City emphasizes economic development in addition to storm protection. With a sixty-five year construction plan, the barrier would be able to withstand nineteen-foot storm surges and would reclaim 500 feet of land. However, community members fear that the rush to develop the area could leave little room for direct community involvement.

In a recent presentation on June 2nd, community officials were displeased with the rendering of what looked like high-rise buildings, which would hinder efforts already in place to restore the historic South Seaport. Damaged by severe flooding during Sandy, the cobblestone marketplace and historic early 20th century buildings have been receiving a gradual facelift; the goal for the community is not to destroy the local character, but to keep it alive and thriving. The Seaport City situation, officials argue, adds to the already, “frantic pace of development in Lower Manhattan,” and an eagerness for newness that ignores the main purpose of the levee, which is to protect New York’s already established infrastructure, not remove it.

Teams from Rebuild have also had their projects come under criticism. The Meadowlands project, which was awarded $150-million to launch its first phase, has regional scientists arguing about the effectiveness of the design. Environmentalists argue that the embankments could actually push storm waters into surrounding communities. In addition, the long-term effects on altering the marshland remain to be seen, with an unknown effect on the local birds, who are still recovering from years of garbage buildup. And some question the effectiveness of the fixed-height berms being implemented, which could become utterly useless if sea level rise is higher than predicted.

Despite these concerns, the Rebuild teams are breaking ground in creating flood protection systems that are custom-built for the unique coastal areas of the metropolitan region. The aforementioned Living Breakwaters, for example, does more than construct a wall.

Philip Orton—an assistant professor at Stevens Institute for Technology and an expert on Physical Oceanography—is a member of the design team who spoke to City Atlas about the emphasis on creating an effective system for Staten Island. (See the full interview on Orton’s blog.)

[pullquote align=”right”]Rebuild by Design projects begin with coastal protection but also may include economic and educational opportunities[/pullquote]“The project isn’t really about “protecting” Staten Island,” Orton argues. “It aims to improve the area’s resilience in a much broader way, including economics and coastal storms. We do this by restoring Staten Island’s historical water culture, reducing flood and wave risks, reducing erosion, improving educational and recreational opportunities at the shore, and thus making the ocean tides and waves (and their risks) more visible and tangible.”

Orton also touched on SCAPE’s plan to rebuild natural oyster beds—which also trap carbon and filter water—around the breakwaters, which will allow the system to grow along with sea level rise, eliminating the design height limitation often experienced with levees. Recalling the events of Hurricane Katrina, Orton points out that when a flood exceeds the levee “you have abrupt rushing water filling in the ‘protected’ area, which can make the hazard MORE deadly than a gradually rising water level. In New Orleans, this occurred many times over and over through history, not just in 2006.”

Coupled with a desire to reconnect Staten Island residents and students with the water through outdoor classes and maritime skill-building, the Living Breakwaters team aims to offer a proposal that not only is a “visible and tangible” alternative to dunes or levees, but is also a system that could theoretically be used in other bay landscapes such as Jamaica Bay, Barnegat Bay, and Great South Bay.

It’s still early in Rebuild by Design’s history to make snap judgments. However, for the time being, the concern remains, in a post-Sandy New York, what the life span of elaborate coastal defenses might be. With the inescapable reality of sea level rise, there is always the background understanding that all of this coastal buffering may eventually be overwhelmed by the ocean. The crucial factor determining that outcome is mitigation — radically cutting the amount of carbon we put into the air — as is also noted in the Rebuild by Design research pack itself.

But these ambitious designs give the metropolitan area hope that their projects might allow us to continue living in the city safe from foreseeable extremes of flooding, while the deeper problem of energy and emissions are solved on the global, national and local levels. The beauty of these design responses to Sandy is that they can also actually improve daily life in the city we all love.

[Correction: an earlier version of this post had the ten team selection of Rebuild by Design in June, 2013, when the selection was made in August, 2013.]

2 Comments

Comments are closed.