Gay Talese tells me that he does not have dire notions about the future of New York. He has lived here since 1953 and has seen the city, in many ways, attacked. But a lot of streets have not changed, and what makes New York, New York, has not changed either.

“It’s a city of optimism and city of change and even bad news changes very quickly here,” he says.

He came to New York after graduating from the University of Alabama. The New York Times hired him as a copy boy. Gay says that in a way it was the most important job that he ever had at the paper, where he would later work as a staff reporter.

When you are a reporter, Gay explains, you have to go out into the city and interview people, chase down the mayor, watch a strike, talk to firemen who have hosed down a burning building. But as a copy boy, you are free to observe the secretaries, clerks, publishers, reporters, editors, advertising directors, floor sweepers, window washers, and elevator operators.

“This is perfect material for me,” he says. “Because I am very curious about ordinary people, not the people who make the news.”

The stories of the people at the New York Times would become his first bestseller, The Kingdom and the Power.

Gay Talese left his job as a New York Times reporter when he was 33 years old. He had already published his first book, New York: A Serendipiter’s Journey, about the people he saw on the streets, and his second, about the building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Gay did not find another place of employment. Instead, he worked out of his house, or rather, below his house. From there, he wrote profiles for Esquire that would becomes classics and books that would become bestsellers, and helped to define literary journalism.

Gay opens his front door—which is being repainted by a man dressed in white who asks who I am here to see—with a hat in his hand. He offers me a seat, and then a drink, and then suggests that we visit what he calls his bunker.

We walk out of the house, then down the steps to the sidewalk where we say hello to the painter. Gay unlocks a door at the house’s right corner. He tells me to slam the door behind me, to be careful on the steps, to hold the banister.

There are no windows in the bunker. There is no telephone. You cannot hear the cars on the street. Gay comes here at 9 or 10 in the morning, and then stays and works until 2 or 3. He follows this routine nearly every day of the week, and it is a routine he has kept since he left the New York Times more than 50 years ago.

The walls, the floor, and the ceiling of the bunker are cream colored. Boxes are stacked up to the ceiling along the left wall. Each box contains the notes for a book or profile and is collaged with mementos from the project: photographs, magazine clippings, the name of the subject. The boxes for Thy Neighbor’s Wife feature nude photos.

At the first desk is the large typewriter with which Gay first writes his stories. At the next desk is a clunky desktop computer that still looks too modern for the rest of the room.

There is a vase of red Calla lilies, a potted tree, a poster that reads: “Mondadori dà il benvenuto in Italia a Gay Talese autore di La donna d’altri.” Red file cabinets along the back wall are full of meticulously dated and catalogued notes from life and reporting. Gay takes notes on shirt boards which he cuts to fit into the breast pocket of his suit jacket. Today, his blazer is cream colored and matches the vest beneath it. When I first walked in, he noticed, and then complimented my dress. Gay’s father was a tailor, and Gay dresses impeccably.

“I buy very few things,” he says. “And I can wear them forever. And if you buy things that are fashioned or stylized in a classical way, they’re never out of fashion. You create your own fashion.”

Gay puts on a jacket and a hat each morning before he walks down into the bunker, even though he will not see anyone there in the day.

“I don’t have lunch with people,” he says. “I don’t want to have lunch. I want to have dinner and I do. Every night. I go out to a New York restaurant. I like to have the city at night with a lot of people around. I like big crowds. I go to restaurants. I go to movies. I go to theater.”

Tonight, Gay and his wife, Nan, will meet the son of Eddy Duchin, the pianist and bandleader, and his wife for dinner at La Veau d’Or, a restaurant that opened in 1937. Peter Duchin is a pianist and bandleader like his father. Despite all the newcomers, many people in the city, such as Peter Duchin, work and live in the tradition of family, and the tradition of New York. Gay points out that the same family has owned the New York Times since 1896.

“All over New York,” he says, “there are grocery stores, there are hardware stores that are family owned, that have been there 3 or 4 generations, struggling to adapt to the new technology, to changing tastes of customers, to all the changes that come about as the way of making a living is altered. And there are people whose grandfathers and fathers before them used to ride these tourist wagon horses in Central Park. Now there are people wanting to get rid of those horses, get rid of those wagons.”

Gay, the son of an Italian immigrant, understands that this tension is one of the constants here. He stayed in New York because, “I didn’t have to be a foreign correspondent. New York was a foreign city. It still is. It changes but it’s made up, as I said when we first sat down, of a lot of newcomers, with new ideas, new languages.” It is a foreign city full of old family businesses. Skyscrapers that are nearly one hundred years old rest beside what Gay calls “glass monstrosities.” The newcomers and the new buildings do not remake the city, they maintain its energy, its optimism, the sense that perhaps things here will be better than they were in Italy or Ohio. New York is a city that does not change, precisely because it remains a city of change.

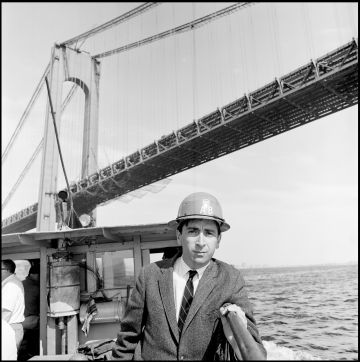

It is a city of construction, and this too is a family tradition. This year there will be a reissue of the 1964, The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge, which Gay wrote while still at the New York Times. When not in the office, he went to the bridge to get the stories of the men who were hanging on cables.

Gay reissues his work because “when I finish a story, I don’t think it’s done. I think stories go on. The book that’s coming out this October, called The Bridge, is a 50 year old revival. It’s got a facelift, it’s got Botox, I mean it’s got a new face in a way. But it’s got the same heart, which was individual risk-taking construction. Individuals climbing high altitudes, 300, 400, 500 feet to connect steel and build something like a skyscraper, build something like a bridge, that lasts forever.”

For the new edition, Gay found the descendants of the men who worked on the bridge. He met a man, Joseph Spratt, whose father was a bridge builder and whose grandfather was a bridge builder. Gay tells me that when he interviewed Joseph earlier this year, he said that:

During this New Year’s Eve holidays, Christmas Eve holidays, he was helping to put up the tower on the World Trade Center, the new Number One tower. And he said he got up there, you know it’s 104 stories, and then it’s got the antenna on top of it, I don’t know how much taller that makes it. He was up there with numbers of other guys his age wearing hard hats working at his business. High altitude work. He said as he looked from the World Trade Center, downtown, down the river, he saw the Verrazano Bridge. And he remembered his grandfather. Then he turned around and looked uptown, and he saw the building that’s over Madison Square Garden, and he thought of his father who was up there doing that. And he said he looked around at these other guys who were his age, up there, at the World Trade Center peak, looking around the city of New York, and they saw all these tall buildings. On the East Side, on the West Side, north and south, down Wall Street, up toward Harlem. All these tall buildings you could still see, him and these other guys. And he was saying, ‘The skyline of New York is a family tree for us.’

The skyline changes. But it stays familiar when you know the people who build it, and it stays familiar because the act of building has the same risk of hanging from cables at extraordinary heights. Technologies becomes obsolete, industry shifts, and the City plans flood walls and thinks about adding a storm surge barrier along the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, but the act of moving forward is not new.

Gay has covered New York in great storms and great fires, a plane crash. But the street where he lives has not changed since he moved in in 1957. He passes through Central Park every day, and has done so for 60 years. He cannot imagine living anywhere else. He is 82 years old, and for the better part of the past six decades he has worked here, telling the stories of obscure people, and obscure stories of some not-obscure people.

He has never been a political writer. “God almighty,” he says. “Can you imagine covering the Senate for 3 or 4 or 5 years? I mean what a non-story that is. Day-by-day, nothingness.”

It is more than the tedium though. Gay never wanted to move from New York to Washington. And he never wanted to make political statements about a statement from the Senate that would mean nothing two days later, or to write a political opinion about a person who one can choose to see in many different ways.

“Too much instant politicization is instilled now more than ever,” Gay says. “Because everybody’s a commentator, everybody has a smartphone, a computer. They communicate with one another by the millions and make up, interpret, immediately interpret what in the not too distant future is deemed ridiculous.”

When Gay sees New York attacked, he does not politicize it.

“Once I saw New York when the electrical system failed,” Gay says. “The whole city was black. I was a reporter, I’m guessing it was 1965, I think it was. And when I covered the city, my first thought was, ‘Who do I want to interview?’ And I thought, ‘Ah, I want to interview blind people.’ So I started, I went over to the Lighthouse which is the center for blind people here, on 59th street. And I watched blind people wandering around the city. Everybody was blind except them.”

Everybody except them and Gay Talese, who was watching them. Gay does not only observe and talk with ordinary people, he is an expert at it. Before I leave the bunker, he has worked out the problems with my romantic life, learned what I have common with my brother, and explained to me how to finish my profile of a woman who works in a plastic surgery practice (his answer: see her naked).

Gay’s genius as a writer is in his ability to see things from so many points of view. He recognizes that every time there is a change toward the new and the good for someone, for someone else there is an accompanying inconvenience or loss of a job. You can think of a place as polluted, and you can also remember why it is so.

“My father was born in Calabria,” Gay says, “which is the poorest part of Italy. It’s the toe of the boot. And he would say when he came to America, which he did in 1922, he’d hear people complaining in America about the industrialization, ‘Oh too much pollution in the air, too much industry, too many cars, too many busses.’ And he’d say, ‘You know, where I come from, Calabria, it’s farm land, hill country, mountains. It has got the purest air in the world and people are starving to death.’ Wonderful atmosphere, wonderful air, unpolluted sky. People are starving to death.”

His father believed that if you wanted fresh air you should go to Calabria, where “You can find all the fresh air you want.” You do not come to New York for fresh air. You come because you didn’t like where you were.

“It’s a city of news and newcomers,” Gay says.

In New York, they become copy boys, reporters, mayors, bridge builders, bandleaders. There is always news, and there are always stories that come not from an interview with a politician or a baseball player, but from sitting down with an ordinary person.

Gay calls his reporting, “The art of hanging out.”

This, then is the way to get at New York and see how its heart remains. The horse-drawn carriages keep riding through Central Park. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge still runs from Brooklyn to Staten Island. Le Veau d’Or goes on serving boeuf bourguignon and moules de roches. The streets stay full of people not speaking in their first languages. And Gay keeps taking notes on shirt boards from conversations with men and women from all over.

“It’s a foreign city of people from elsewhere who have a lot to give,” he says. “But not only a lot to give, but sometimes a difficult time explaining it.”