[Over coming weeks, the staff of City Atlas will be presenting summaries, analysis, and public feedback on the city’s monumental SIRR report about rebuilding and resilience, which includes lessons learned from Hurricane Sandy and plans for the city in the face of new challenges from a changing climate.]

By Johanna Goetzel and Jody Dean

Extreme events often prompt questions that begin with “why?” Why now? Why me? Why here? Due to the chaotic nature of the climate system, there is no simple answer to these questions. Part of the answer, though, can be found by examining past climate trends and projections for the future. Extreme events like Sandy cause huge impacts, the most jarring being the loss of lives and the displacement of people from their homes. There are also massive monetary costs associated with rebuilding. We will all bear the burden of these costs, through taxes and resource reallocation.

The Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency (SIRR) report offers targeted suggestions for policymakers regarding the development of more resilient systems for New York, in order to make the impacts of extreme events and climate change manageable rather than catastrophic.

In time and with the increased political gravitas delivered by this extensive report and ongoing discussion around it, the conversation can shift from “why did this happen to us?” to “how can we adapt and rebuild responsibly”? This refocused question allows us to move forward and is made possible by understanding the chronic hazards faced by the city and the potential impacts of extreme events, whose frequency and severity are likely to increase with the changing climate.

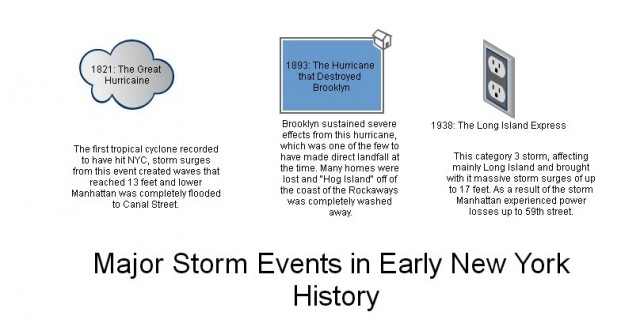

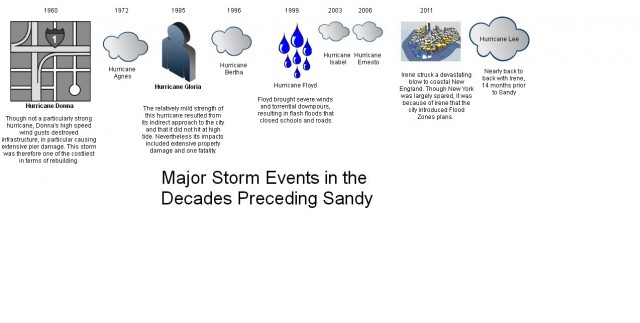

The full report includes a climate analysis section (hi res pdf) that documents the impact of historic extreme weather events and provides a context for future climate scenarios, along with the projected costs. The SIRR utilizes climate models developed for the forthcoming Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5). The AR5 concludes that “long-term changes in climate mean that when extreme weather events strike, they are likely to be increasingly severe and damaging.” Despite the extreme and historic nature of the event, Sandy was not the first storm to cause significant damage. The timeline below illustrates other coastal storm events with major impacts on New York City. As with Sandy, the effects of these storms were experienced all along the Eastern Seaboard.

The vulnerability of the city to coastal storms is nothing new, but as previously noted, climate change will exacerbate the situation by worsening extreme events and chronic conditions. As indicated in the IPCC AR5, over the past century sea levels in New York City have risen over a foot, while simultaneously temperatures are increasing. The scientific consensus is that these trends will accelerate and this is highlighted in the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC) 2013 climate projections, which were included in the SIRR report.

Source: NPCC

In addition to these chronic hazards, another vulnerability highlighted in the SIRR is the city’s use of outdated Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRM’s), which show the percentage of land that lies within the so-called “100-year” and “500-year” floodplains. At the time that Sandy hit, the FIRM’s had not been updated since 1983, though in 2007 the City formally requested that FEMA update the maps to include the last 30 years of data. The lack of updated maps left the city with an inaccurate view of the percentage of land at risk for flooding and the areas that flooded during Sandy were several times larger than the floodplains outlined in the 1983 FIRM’s. The SIRR emphasized the importance of regularly updated maps to assist with adaptation and mitigation strategies for coastal flooding.

The climate analysis section also explained the frequently misunderstood classification of a “100-year” or “500-year” event. Classifying an area as part of a “100-year floodplain” indicates that there is a 1 percent chance of a flood occurring in the area in a given year and that experiencing a 100-year flood does not decrease the chance of a second 100-year flood occurring that same year or any year that follows. Following these calculations, Klaus Jacob writes in the June issue of Scientific American that, “the chance of what had been a one-in-100-year storm surge occurring in New York City will be one in 50 during any year in the 2020s, one in 15 during the 2050s and one in two by the 2080s.” The city is now working again with the NPCC to develop more accurate “future flood maps” to assist with the rebuilding, planning and adaptation efforts.

The climate analysis section concludes with specific, forward-looking initiatives for planning along New York City’s 520 miles of coastline, including a network of floodwalls, levees and bulkheads to protect buildings and inhabitants. More than encouraging “emergency preparedness,” longer-term scenario planning will be necessary in order to adequately safeguard New York and its growing population. Further, climate projects need to be regularly updated in order to adequately inform decision making.

Advocating that we “plan ambitiously,” the SIRR report suggests that mitigation efforts require buy-in from policy makers, planners and insurers and civil society. Cynthia Rosenzweig, NPCC co-chair, makes the salient point that adaptation plans cannot succeed “without taking the voices of neighborhoods into account.” In order to best address questions of “why me,” vulnerability must be analyzed at multiple levels and the resulting plans backed by financial investment for addressing the continued threat of climate change. Above all, the SIRR report emphasizes that building capacity for resilience requires accurate data to assess the potential impacts and the tools and financial resources available to implement solutions.

The full report can be found here, and is a marvel of lucid explanation: it’s a self-contained, benchmark work that integrates climate and urban planning for the most populous city in the world’s largest economy.

Additional Reading:

-Coastal subsidence also plays a role in NYC coastal vulnerability. Providing historical analysis and vivid maps, Mark Fischetti’s Scientific American article explains how North American glacier retreat began over 20,000 years ago and little by little, has resulted in the eastern U.S. landmass sinking as the crust adjusts to the unloading.

-The question of whether or not rebuilding after natural disaster has been hotly debated since Sandy. Tom Ashbrook tackled this question in a February 2013 On Point Podcast.

– Our interview with Klaus Jacob, who also raises the question of rebuilding in areas that will become increasingly endangered over time.