We live in turbulent times: mainstream cinema has a desperate preoccupation with the apocalypse; no one holds their breath for the president’s commitment to addressing climate change, and even the idea of living sustainably, in an aspirational country, sometimes seems to mean slapping a solar roof on a 5,000-square foot mountainside home accessible only by a sport utility vehicle. Meanwhile in NYC, the mayor has committed much of his last few months in office to fortifying the city against a changing climate.

Into this hectic cultural landscape, Eric Sanderson, senior conservation ecologist in the Global Conservation Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society, brings a message of common sense and optimism–the two most American of virtues, at once startling and familiar.

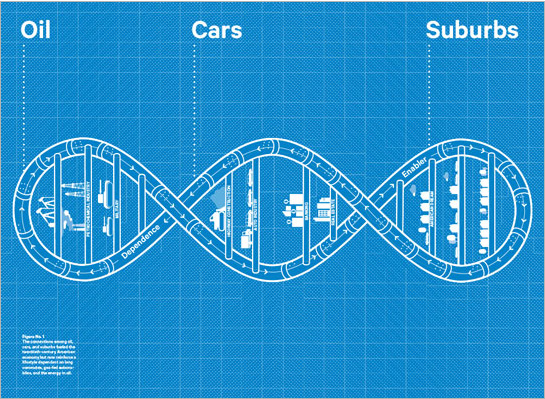

Last week, Sanderson spoke at 92YTribeca with Alexandros E. Washburn, Chief Urban Designer of the City of New York, about his new book, Terra Nova: The New World After Oil, Cars And Suburbs. Sanderson introduced his book with the facts: we have a continued dependence on oil, which is dwindling, and our environment is on the brink. Comparing oil, cars, and suburbs to the siren song that lured sailors to their doom in the Odyssey, Sanderson underscores the reality that we are wholly beholden to these three taskmasters. We live in the suburbs, therefore we must drive cars. We drive cars, therefore we must use oil.

Like Odysseus, we need only learn something about ourselves in order to chart a new course. According to Sanderson, that ‘something’ is the “American presumption” that land and its resources are eternally abundant.

“This idea that there’s always more to be had is rooted very early in our history as a country. The Europeans who came to this part of the world assumed that there was all this free stuff to take. For… at least the first 200 years of our country, there was always more space to take. That meant that our economy became addicted to that presumption,” says Sanderson.

Indeed, as Terra Nova reveals, the United States once led the world in oil production, and the U.S. economy, in which land, labor, and capital were infinite and bountiful, sparked the competitive American entrepreneurial spirit as we know it today and birthed the first major monopoly, Standard Oil (which was later divided and recombined into the modern colossus Exxon/Mobil, the world’s most profitable company, and Chevron).

Unfortunately for us, the American way of life — predicated on an assumed abundance — is a dangerously appealing lifestyle. Not only are we destructive: people want to copy us in China and India, creating vast new markets for cars.

Oil, according to Sanderson, has seeped into our collective subconscious, perpetuating the American Dream as using a 4,000 lb. vehicle to drive twenty minutes to get to the nearest grocery store. To be American is to drive.

The emphasis on labor and capital has also changed the language in which we communicate. Since 19th-century industrialization, money has done the talking. So what are we left with? An economy intricately bound to the environment; millions of Americans who have a stake in this economy; a culture in which money speaks louder than nature or our own words. How do we escape a feedback loop of irresponsible understanding of natural resources and their subsequent underappreciation and inefficient use?

Sanderson plays interpreter and digs a way out by using the resources we have, in a language we speak and understand, with the values we cling to: taxes, money, and the occasional ego boost.

He proposes gate duties, a system of taxation through which we literally value American nature and pay its full cost: “Taxing the things we don’t want—inefficient resource use, excess waste production, and relieving existing taxes. So not adding new taxes to the economy, but actually shifting taxes from the interior of the economy to the exterior,” explains Sanderson.

One manifestation of gate duties would be ecological use fees, based on the same principle of a property tax. Instead of being taxed for the value of your property, you are taxed for the ecological value you take away from the public when you build something. For example, if your home were settled on a former wetland that could be used to provide storm resilience, the government would stop by to collect.

All in all, Sanderson has given nature a mouthpiece that facilitates its communication with the economy and essentially to us (using implements–taxes–that we’re already accustomed to). “If we could make the economy talk to nature, it could work for our long-term sustainability,” he says.

But Americans have something more to gain in valuing nature. “Particularly in this world where everyone is scrambling to get natural resources, what’s the long term future for America? It’s actually to be the country that has the strongest natural resource base, and the most talent, and the best capital markets. If we can be that in 2100, then that will be the basis for sustainability to last for hundreds of years.”

As Washburn put it, Sanderson has created a “blueprint for success” for American innovators, policy makers, and average citizens alike. He continues, “[Sanderson] just named the ingredients of making America the primary force for good in the world for another century. If anything, that’s the American dream, that we live our lives in a way that the rest of the world wishes to emulate.”

Terra Nova may be a wedding of current American ideals, beliefs, behaviors, and practices to a feasible plan for a sustainable future. It may also signal the growing collaboration of ecologists and economists to tackle an animal that has outgrown the disparity between the fields. For Sanderson, the wisdom necessary to reach a sustainable future may signal the break of continuity with the past more so than post-apocalyptic cinema, isolated solar panels, or even gate duties ever could.

Eric Sanderson & Alexandros E. Washburn discuss Terra Nova at 92Y in New York: