The city’s Special Initiative on Rebuilding and Resiliency, or SIRR, is a 438 page document released in June, 2013 as a response to the impact of Hurricane Sandy. The SIRR report provides a set of strategic initiatives to prepare the city for decades to come; here we present the fourth in our series of summaries of the report, distilling the chapter on South Queens with amplification from other media and recent events.

In addition to its beaches, surfing, and seaside lifestyle, South Queens combines a vulnerable coastline with a population ranging vastly in class from wealthy, single-family dwellers to many residents of nursing homes and other medical facilities, as well as public housing projects. The city’s SIRR report seeks to unify the area with common values, using Hurricane Sandy as “a new chapter in the common history of South Queens,” though the range of income and opportunity across side-by-side neighborhoods is stark. All together about 130,000 people call the area home.

South Queens includes Rockaway Peninsula, 11 miles of the only unobstructed coastline in New York City, which acts as a barrier island between the Atlantic and Jamaica Bay. The total area covered in this section of the report includes the waterfront neighborhoods of Far Rockaway, Belle Harbor, Broad Channel, New and Old Howard Beach, Hamilton Beach, and Breezy Point, which was created entirely by moving sediment over the past century and was nearly destroyed by fire and water during Hurricane Sandy.

Last year’s hurricane caused significant flooding, with 1.5 million cubic yards of beach sand blown into streets and properties, and fire, with 175 homes and businesses ruined.

The SIRR report says that rebuilding is not enough, but rather that new layers of protection must be added to these vulnerable communities as climate change continues. The greatest risks are storm surge, rising sea levels, downpours, and heat waves. The plan also seeks to “build on the area’s natural assets, local economic strengths, and community spirit to encourage reinvestment in its waterfront neighborhoods.”

Because of the dramatic damage after the storm, the Rockaways were heavily covered in the media, and continue to stand as a symbol of changes wrought by Hurricane Sandy.

South Queens is characterized first by homes and then small businesses (with some large healthcare employers and facilities), as well as six NYCHA and seven Mitchell-Lama public housing and nursing homes previously mentioned. Unique to the area are its natural resources: beaches, parks, and Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, a famed birdwatching location for the East Coast.

78 percent of the area’s residential buildings were constructed prior to the stricter building code standards adopted in 1961. There exists wide socioeconomic stratification across these neighborhoods: Broad Channel’s poverty rate is 1 percent whereas 22 percent of Far Rockaway’s residents live below the poverty line. Small businesses, plus larger healthcare facilities, dominate the economic activity. Seasonally, concessions and lifeguarding provide temporary work. Even before Sandy, much of the area was struggling financially.

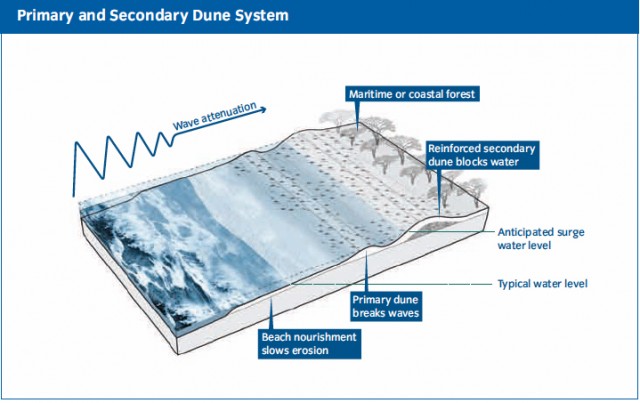

South Queens as a whole contains much critical infrastructure, including transportation and a wastewater plant. The beaches also provide infrastructure for coastal protection. From 1977 to 2004 the Army Corps of Engineers continued “beach nourishment programs” to protect the coastline, but this ended due to costs, apparently, and the beaches have continued eroding.

The SIRR report includes a detailed description of the damage and devastation to homes and businesses done to the area during Sandy.

There are special sections on fires, power outages, and three degrees of building damage (destroyed, red, and yellow). Homes and businesses suffered lasting impacts, with, for example, only 40 to 50 percent of businesses in Far Rockaway able to open for at least three weeks after the storm. Transportation–both road and rail–was deeply affected. The A train did not regain service until summer 2013. The area’s waste water plant did not regain full capacity for two weeks after the storm, segments of the boardwalk were destroyed, and 37 schools in the area were closed for up to two months. The summary also praises the efforts of community groups, residents, and outside volunteers, and singles out by name Rockaway United, a group of 40 local organizations that coalesced to coordinate post-storm services.

Short film for rockwayrelief.com by Phillip Van

One aspect of the experience in South Queens stands out from other parts of the city. In recent decades the subway-accessible beach and surfer culture in the Rockaways attracted New York’s young creative community to the waterfront. After the storm, many young people from around the city rapidly mobilized to help residents dig out, self-organizing before any government or NGO relief was underway. Skilled photographers and filmmakers among them made indelible images of the Rockaways central to the ongoing narrative of Hurricane Sandy.

Creative initiatives soon sprang up to support the area: Walter Meyer and R. David Gibbs, an architect and engineer who both surf, gathered a team to create Power Rockaways Resilience, bringing solar power to the damaged community. Klaus Biesenbach, director of MoMA/PS1, has a home in the Rockaways and was active in rallying support from prominent people in the world of arts and media; as rebuilding began in the spring, MoMA/PS1 organized a design contest for a sustainable waterfront. The resulting work, with entries from around the world, was exhibited in a popup space sponsored by Volkswagen at Beach 94th Street.

Another unique feature of South Queens is the founding of the new Jamaica Bay Science and Resilience Institute, which will give the area a world-class resource for the scientific study of coastal resilience.

The future:

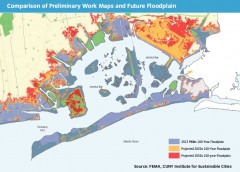

The FEMA maps previously used to determine the “100 year floodplain” were outdated by twenty years. Since 1983, the area at risk and the buildings there have increased rapidly. The entire area of South Queens now lies within 100 year floodplain territory, with several neighborhoods at risk to higher flood elevations and chronic flooding.

The beachfront of South Queens is open to the Atlantic. The recent example of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, which produced sustained winds of 190 mph at landfall, gives meaning to a passage in the SIRR about planning for wind and adapting housing going forward:

“While future projections for changes in wind speeds are not available from the NPCC [New York City Panel on Climate Change], a greater frequency of intense coastal storms by the 2050s could present a greater risk of high winds in the New York area. This could cause issues for materials that are exposed and for buildings built before modern building codes—of which South Queens has many.”

Though New York hasn’t yet seen a storm as powerful as Haiyan, Atlantic hurricanes with similar speeds have struck the United States, including Hurricane Camille in 1969.

Whether storms become more frequent in a warming world is unknown; they are expected to increase in power, as shown in this explainer from the New York Times:

Priorities gleaned from SIRR’s “public engagement” include:

• Providing coastal protection measures on the

ocean and bay;

• Clarifying available resources to retrofit, repair, and rebuild homes;

• Addressing concern over future flood insurance rates;

• Providing support to small businesses;

• Expanding transit options; and

• Creating jobs and access to job training and

educational opportunities for local community members

The Plan

According to the end of SIRR’s South Queens chapter, most planned initiatives were ready to proceed, with funding sources identified, at publication. These initiatives include:

Coastal Protection, including a revival of beach replenishment activities which ceased in 2004. By December 2013, a projected 3.6 million cubic yards will be replaced. Bulkheads will be raised (“subject to available funding”) to protect South Queens and other vulnerable coastal sites, and the Belle Harbor seawall repaired.

Additionally, the city will call on the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to complete a Rockaway reformulation study that was started a decade ago and never completed. Now by 2015 the study should conclude whether safeguards such as a primary and secondary dune system and additional wetlands (for wave attenuation) should be implemented.

The SIRR’s stated plans for buildings include retrofitting buildings, improving building regulations for flood resiliency, rebuilding destroyed and damaged housing units, and collaborating with New York State to identify communities eligible for home buyout. If the money is available, there is also to be a competition held to encourage new housing types to replace vulnerable building stock.

Insurance

The city estimates that less than 31 percent of residential properties typically insured under the NFIP actually had flood insurance coverage prior to Sandy. The report’s plans include calling on the city and FEMA to finish a flood insurance affordability study, and to allow insurance policy-holders to select higher deductibles.

Critical Infrastructure and Utilities

About 131,000 Queens residents lost power and natural gas access during and after Sandy. The SIRR claims it will work with the PSC to harden natural gas supply lines and overhead power against flooding and winds. There is also note of expanding microgrids.

In terms of Liquid Fuels, the report promises to strengthen gas stations against extreme weather by encouraging New York State to offer incentives. A subset of gas stations, says the report, should also be allowed generators for backup power.

Healthcare is of huge importance in general in the city, and in particular in South Queens, where a great deal of nursing homes and other healthcare facilities depend on power and other basic functions to care for their residents. Nursing homes and other facilities in the floodplain will be required to retrofit for resilience, and the backup power supply for pharmacies increased. There is also a dire need for increased telecommunications between healthcare facilities, particularly during disaster time. The report pledges to help support nursing homes and adult care facilities with mitigation grants and loans.

South Queens was hard-hit in the days, weeks, and months after Sandy in terms of transportation. Major goals outlined in the report include restructuring street surfaces, increasing Select Bus Service to South Queens, creating alternate transportation plans for prolonged subway shutdowns, and increasing ferry service to the Rockaway Peninsula–in certain times, when road and rail fail or are upended, the water is the most reliable thruway.

Parks

Restoring South Queens’ beaches was and is a major part of the SIRR plan. Also included, importantly, is the effort to transform Jamaica Bay. Shoreline parks must be modified, with floodwalls and other infrastructure, to protect adjacent neighborhoods. A study for best practices is to be completed in 2014.

Water and Waste water, Food Supply, and Community Economic Recovery initiatives are also outlined in the SIRR. Many initiatives address longstanding needs, and some immediate solutions (i.e. restoring beaches) have already been completed or are underway. Much is left to be desired in terms of direct action for the communities of people and other living beings in the area. As an Occupy Sandy representative told us not too long ago, the “bold and unfunded ideas that came out of a ‘community process'” included in the SIRR report often fall short.

A year after Sandy, there is much organizing and much strengthening to do. South Queens, deep in creative, scientific, and natural resources, will be taking a frontline role as New York City adapts to the future.