When the Brooklyn Botanic Garden announced late last month that it would be closing the doors to the garden’s research facility in Crown Heights for an undetermined amount of time, many foresaw the end to research at the garden’s unique library of over 300,000 dried plant specimens. The public reaction to the notice that research would be temporarily suspended at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden Science Center, and that four researchers were laid off in late August, was strong.

Among other critics, Chris Kreussling, the Flatbush Gardener blogger, initiated a petition on change.org that blames the current Board of Directors at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden for straying from the garden’s mission to conduct research in plant sciences. The petition calls for the Brooklyn Botanic Garden to do three things: restore the garden’s field work, herbarium and library access, including the laid-off researchers, staff and programs that run it; (re)prioritize science, as called for in the garden’s mission statement; and create a more transparent community with Brooklyn and its neighborhoods regarding changes in the garden’s research decisions. Over 1,500 supporters have signed the petition.

Kreussling has framed the recent structural changes as a breach of ethics, or what he has called “not a singular event…by which BBG has eroded its science staff, programs and activities.” And beyond that, Kreussling and others are also concerned with the larger issue at hand: will the research hiatus at the garden prompt the deterioration of plant science research all over the world, much of which has in fact relied on resources at the garden’s plant library?

According to plant scientists and supporters of the petition, the degree to which researchers have relied on the BBG’s plant library should be fully understood. The garden’s herbarium has dried specimens of local flora as far back as the 1700s, which has been critical for “conservation efforts, plant identification, and understanding of the natural history – and future – of the region,” according to the change.org petition.

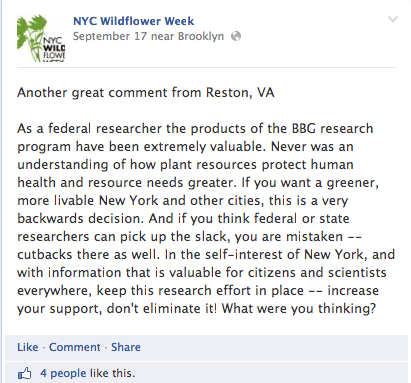

NYC Wildflower Week, dedicated to “creating a cultural framework to engage and connect people with their local environments,” has weighed in on the issue too, endorsing the change.org campaign launched by Kreussling.

For now, the Daily News has reported that a garden spokeswoman has said that during the suspension of research activity, there will be “limited” access to the garden’s herbarium. Brooklyn Botanic Garden officials are still in the process of finding a warehouse suitable to store the plants, many of which are sensitive to heat and humidity changes. According to Garden President Scot Medbury, the changes come in light of the stretched resources of the garden, including “increased insurance and employee-benefit expenses.” The Brooklyn Botanic Garden has also recently expanded its Native Flora Garden and built a new visitors center.

The cutbacks at the botanical garden struck a nerve among local ecologists, as there is already concern that there is a drift away from protecting plants native to New York City. Urban conservation biologist and Executive Director of NYC Wildflower Week Mariellé Anzelone wrote an article in June for the New York Times wherein she argued that incorporating a “farm-filled landscape” with imported fruit trees and plants rather than native plants could do more harm than good. Anzelone notes that a landscape without native plants undermines bee’s critical role in the ecological process, in that imported plants do not provide as much of a fixed supply of nectar as wild plants do. The status of wild, local plants occupies a precarious position in New York City, oddly challenged by the success of a new and growing cohort of urban gardeners that make use of green spaces in the city for plants that are not necessarily native. Ideally, both cultivated landscapes and wild landscapes can flourish in the five boroughs, but the changes at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden have brought to light the importance of the substantial science resources, often taken for granted till they are lost, that track our local ecosystems.