In light of the mayoral candidate debates starting to heat up, Transportation Alternatives released its new platform for what it believes is essential for the city: safe streets. The recommendations from Transportation Alternatives have been overlapped by the city’s 2012 traffic fatality report, released in March, and discussed in detail in the New York Times on April 2. The take-away shows progress overall, but a disturbing picture of continued accidents for both bicyclists and pedestrians with the right of way: among pedestrians injured while crossing the street, “44 percent used a crosswalk, with the signal,” and were still hit by a vehicle. (And every day brings a reminder of how streets can be dangerous, with April 3 being a bad day in particular.)

The “Safety First Plan: A Five Borough Blueprint for New York City Streets” outlines three key points for improving the safety of the city’s streets:

1. Safe Neighborhood Streets For All: To ensure neighborhood streets offer safe space for local families, seniors and children to bike, walk and play, the City must fulfill local demand for Play Streets, 20 mph Slow Zones, bike lanes, Safe Routes to School and Safe Routes for Seniors in 50 neighborhoods a year.

2. Transportation Choice On Commercial Streets: To guarantee New Yorkers have the safe and convenient access to local businesses allowed by a robust variety of transportation choices, the City needs to provide protected bike lanes, Select Bus Service, bike share and pedestrian refuges and plazas on four major roadways in each of the city’s five boroughs each year.

3. Zero Tolerance Traffic Enforcement: To make New York City streets as safe as they can be, the New York City Police Department needs to enact a zero tolerance policy for dangerous driving by setting a multi-year goal of eliminating traffic deaths and cracking down on the deadliest traffic violations like speeding and failure to yield.

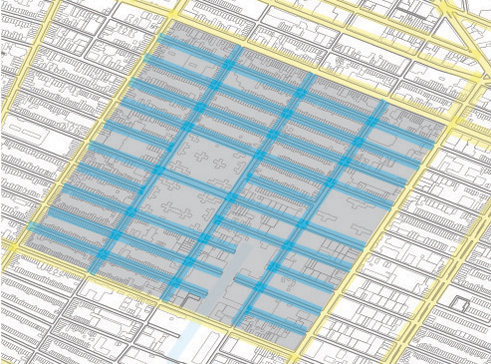

One of the easiest ways to make cities more walkable and bikeable requires no funding or construction at all. Lowering speed limits is an effective first step to creating safer streets for pedestrians and cyclists. In conjunction with other traffic calming instruments, like speed bumps, colored road painting and other signage, neighborhoods with lower speed limits enjoy fewer accidents and more confidence in childrens’ and elders’ safety. Transportation Alternatives and the Department of Transportation are now accepting applications and suggestions for the next slow neighborhood installment in areas about five by five blocks large.

Slower traffic also invites more cyclists onto the street. A Department of Transportation survey showed that most New Yorkers cite safety as their number one reason for not biking, and so slower traffic would reassure bicyclists. The plan additionally encourages the city to install more protected bike lanes, the isolated and painted lanes seen on 8th and 9th Avenue, and the lower stretch of 2nd Ave., and the separated bike paths on Grand Street and Prospect Park West. Protected bike lanes are much harder and most costly to install than painted lanes on the street, but make cycling much less intimidating, and so reward the city with greater ridership — which is a win-win-win for the city in terms of reducing car congestion, trimming carbon emissions, and improving public health.

More info from Transportation Alternatives, here.

More activism about traffic safety comes from the Living Street Will project, which is collecting pedestrian’s and cyclist’s video statements to the police, to be used in the event of their death in an accident. See their site here: streetwillsnyc.com

Photo: Department of Transportation