In the concept above, steel panels decorated with art are part of an overhead structure that can swing down and lock in place to form a flood barrier along the East River. The panel concept is part of a winning design called “The Big U” that is now the basis for a wrap-around levee for Lower Manhattan. This is one step in how the city plans to cope with rising sea levels brought on by climate change.

Plans for the first sections of the new infrastructure, renamed by City Hall as the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency project, were recently presented in workshops for input from local communities. Angie Koo and Marlyn Martinez covered two workshops and report back below. But first, some broader context.

Prominent news stories over the past few months have zeroed in on the rising estimates of sea level impacts on cities around the world. The underlying research has been covered in City Atlas, in conversations with James White and Klaus Jacob.

Major newsrooms, many in cities near sea level, have picked up the pace, and stories now regularly appear either set on the great ice sheets (Elizabeth Kolbert for the New Yorker, Justin Gillis of the NYT on researcher Gordon Hamilton) or on the coastlines that are confronting adaptation or retreat. Josh Fox’s short film in Vanity Fair looks at Manhattan at risk from sea level rise:

One project released this month will stand out: Leonardo DiCaprio’s documentary for National Geographic, “Before the Flood.”

It’s going to be hard for the public to avoid this information, and our social choices are already bewildering. Coastal cities are hard to contemplate giving up, but now many are on some sort of clock, and only our own rapid changes, towards effective governance and a plunge in the rate we burn fossil fuels (likely meaning in the near term, an associated drop in our use of energy), will slow the clocks down.

Our ability to govern ourselves, either as individuals or as groups, may be inhibited by the attempt to fit economic norms, the principal mechanism of global negotiations, to a problem too vast for economics alone to solve.

For example, in what economic system would the loss of New York City be ‘worth it,’ or, a ‘good deal’? The new construction to protect the city from rising seas is still only a temporary fix; without a rapid drop in global emissions, our current planning will be obsolete in less time than has elapsed since the construction of the Empire State Building.

The animation below (by @ClimateCollege) shows cumulative global emissions from 1850 to the present. New York City needs for the world to hold to the ‘1.5°C Budget’ in order to remain intact. In the case of overshooting the target, carbon might be later withdrawn from the atmosphere in order to return to the 1.5°C benchmark. Carbon capture is theoretically possible but daunting to accomplish at the scale needed. Because building a new, non-carbon global energy system commits us to spending a portion of future emissions in its construction, we may be close to having expended our budget already, meaning that many of our activities today may already be dependent on us being able to recapture the carbon at a later date. (This is the most important fact about our economy and lifestyle choices that the public does not know.)

How fast is fast enough to address a problem that requires enormous changes?

The workshops to explain the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency project provide a model for public participation. But every public conversation about adaptation now must be matched by a conversation of equal duration about mitigation. A steep drop in emissions needs to begin immediately in order to improve our adaptation chances.

Economists and our political system may both be at a loss on how to react with adequate speed, but our science, and the underlying civilization which produced that science, is still first rate. We now know what we’re doing, and citizens can still decide, individually and collectively, not to do it. Angie Koo and Marlyn Martinez report:

The importance of community meetings

In a recent visit to Miami, where one of us (Marlyn) participated in workshops similar to the New York meeting, Miami attendees shared their water related stories and they connected instantly. With the exception of accidents and hurricane-related disasters, living by the ocean shapes Miami residents from childhood to adulthood in positive ways.

New York has a different history. The construction of the FDR Drive, industrial uses along the river’s edge, and the level of pollution in East River long dissuaded Manhattanites from enjoying the waterfront. This has changed through the years and residents are getting closer to the water in all sorts of ways. Keeping neighborhoods safe must be part of the conversation.

What do residents in Lower Manhattan value the most about their neighborhoods and about living in close proximity to the water? This is what the LMCR group is trying to find out. This information will guide them during the design of solutions that fulfill their needs and wants while offering protection in from the elements in a rapidly changing environment.

On July 27 and 28 (and repeated on October 5 and 6) the Lower Manhattan Coastal Resiliency (LMCR) held community engagement workshops, one for the Two Bridges neighborhood and one for the Financial District and Battery Park City area.

These meetings were to assess public opinion on flood prevention plans. The project, formerly known as the “Big U”, grew out of the devastation caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

In total, approximately 60 people attended each night, not including facilitators or organization representatives. The workshops largely mirrored each other in setup and structure; if you haven’t been to a community meeting like this, here’s how they worked:

- Opening Remarks

- OneNYC: Our Resilient City

- Project Overview

- Question and Answer

- Small Group Discussions + Activities

- Coastal Resiliency Infrastructure Types

- Community Priorities

- Report Back + Questions

- Next Steps

About five participants sit at each table, where a facilitator and a planner or designer leads the small group discussions and activities. Before that portion of the workshop, we received a presentation on resiliency efforts citywide and how this specific project came about, and how it will be implemented.

If you were lucky enough to avoid long term damage it may be getting hard to remember the scope of Hurricane Sandy. According to the City, “88,700 buildings were flooded; 23,400 businesses were impacted; and our region’s infrastructure was seriously disrupted. Over 2,000,000 residents were without power for weeks and fuel shortages persisted for over a month.”

The Two Bridges neighborhood, the Financial District, and Battery Park experienced several feet of flooding. In all, Sandy cost the city over $19 billion in damages and lost revenue, and exposed Lower Manhattan’s vulnerabilities to climate change, particularly flooding. Recognizing that this needed immediate attention, the city jump-started efforts to plan a more resilient city.

The last iteration of PlaNYC, the Special Initiative on Rebuilding and Resiliency, was released in June, 2013 by the Bloomberg administration, and sketches Sandy-inspired coastal defenses that the city continues to develop. In April of 2015, Mayor de Blasio released his new long-term strategic plan and vision entitled OneNYC, as an update to the Bloomberg administration’s reports.

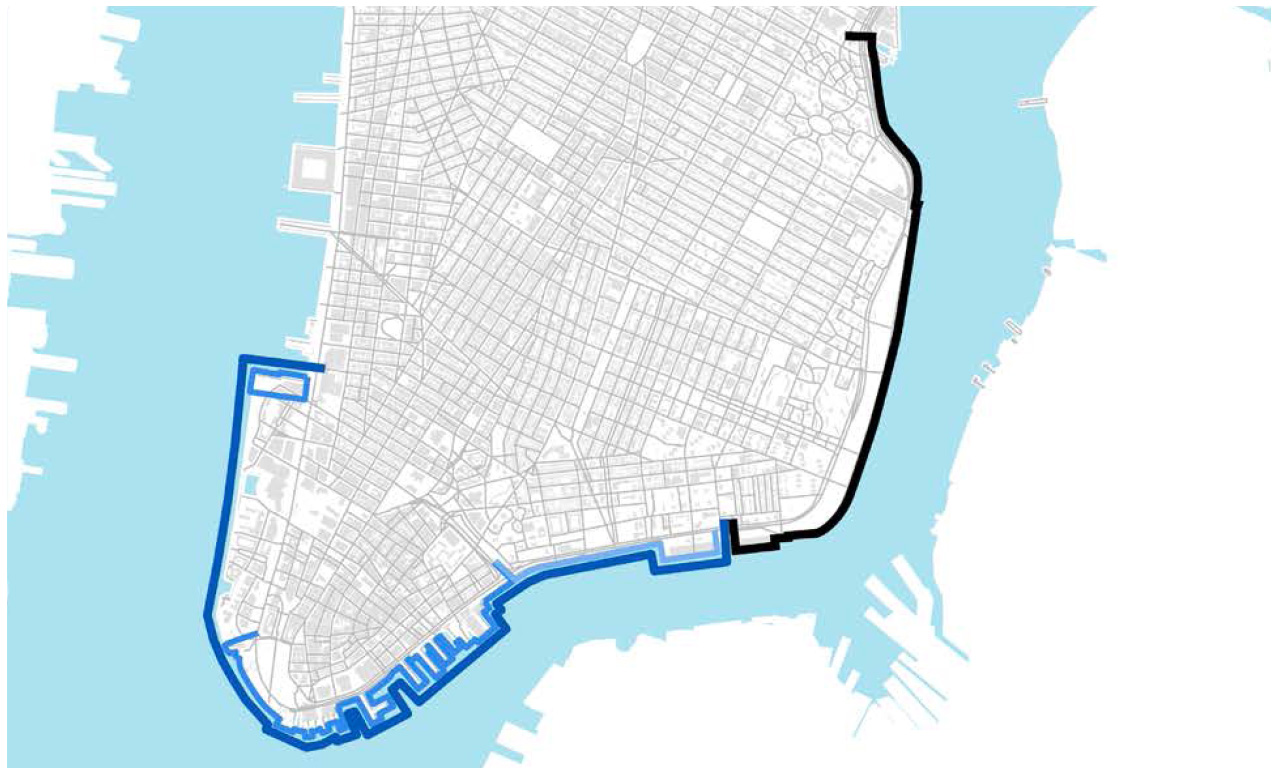

Lower Manhattan though, required a faster response, and working funds have been pouring in for a range of initiatives. In 2014, an initial $108 million was directed to Lower Manhattan by the de Blasio administration, for implementing coastal storm protection infrastructure. In January 2016, the Two Bridges neighborhood–from Montgomery Street down to the Brooklyn Bridge–was awarded $176 million from the Federal Government, through the HUD National Disaster Resilience Competition for integrated flood protection, and another $27 million came from the city’s budget.

Alongside these efforts to provide comprehensive flood prevention to Lower Manhattan is the East Side Coastal Resiliency Project. Also initially funded in 2014, the East Side portion aims to bring similar measures up to 23rd Street from the Brooklyn Bridge.

Overall, the LMCR project consists of four main activities before the final design can be implemented, as framed for us at the workshops we attended:

- Build from previous and existing planning and design of the areas

- Develop a comprehensive design concept

- Evaluate the feasibility and prioritization of the design

- Scope near term implementation

The workshop organizers emphasized being mindful of other planned or existing projects. The efforts of LMCR do not exist in a vacuum and the representatives in attendance seemed keen on making sure the end-product fits naturally into the landscape.

At each step throughout the project, community input will be taken account through workshops, informal engagement, interviews, focus groups, surveys, and tours of the neighborhoods. The focus on local engagement means to ensure the project’s acceptance in the community.

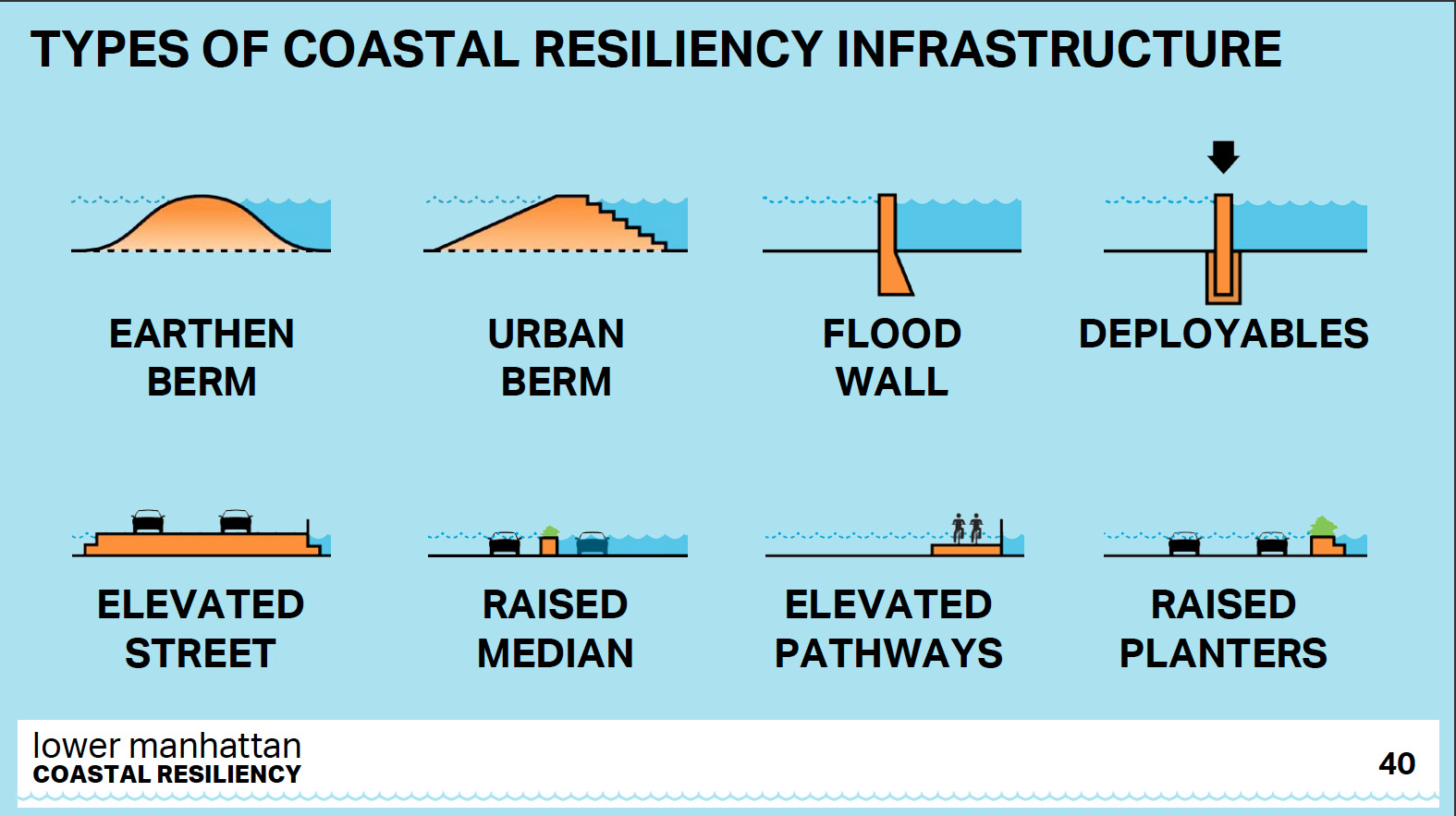

During the small group sessions we took part in two activities: First, a discussion of seawall design and implementation. Participants were given a list of images and descriptions of possible seawall designs to be built in the areas prone to sea water intrusion, a chance for the designers to listen to the community about what types of seawall infrastructure residents would like best.

In the second activity, participants were given a poster size sheet in which to create a communal list of priorities. Stickers labeled as: reliability; maintenance & operations; waterfront access; views; safety & lighting; look & feel; recreation; and amenities were placed in one of three zones indicating the level of importance. Red stickers were for residents, blue for everyone else.

Two Bridges

My table from the Two Bridges workshop immediately gravitated towards the types of seawalls that could be seamlessly incorporated into the existing environment, like berms. We did agree though that where areas are already limited in space, a flood wall (more compact) may be the best option. The area near Brooklyn Bridge where there is already a concrete divide between people and water would be an example.

Overall, our main concern with any type of seawall was if it would mean losing access to the waterway, visually and physically. Specific to deployables – removable partitions that would be attached when a major storm approaches – we were skeptical of having to rely on human action. There will always be questions of if and when should they be used. People don’t want to deploy them too far ahead of a storm because it’s visually unappealing and would be a drain on resources should the storm not hit the city. Deployables encourage us to wait to the last moment before acting. Should there be anything amiss with them that cannot be fixed at a moment’s notice, the consequences could be severe.

During the second activity, where we judged priorities, there were two clear messages conveyed by all the participants: reliability and waterfront access. As one participant said, “It has to work.” Just as important, especially to the residents, were access and view of the East River. More than one table said they did not want permanent walls and if a wall must happen, it should be glass. Residents were also quick to point out that they wanted whatever was going to be implemented to be done with the residents in mind, not speculative residents or tourists. The existing community, with a sizeable population of young children and seniors that enjoy the waterfront, must be prioritized.

Financial District and Battery Park City

At one of the tables from the Financial District and Battery Park City meeting, the consensus was that a single type of seawall won’t work, and that solutions should be chosen for the characteristics of each area. Some areas require a combination of seawall and elevated streets, while others could have walls that double up as green spaces. The main concern among the five participants at the table, who were not residents of the area, but are worried how sea level rise may affect them in the future, was the reliability of the seawall designs that require deployment or installation before an event that may cause flooding is expected. Who will deploy them? Is electricity required? What will happen if the power is off? These were some of the questions raised.

Reliability was chosen as the number one concern at our table, and this was true for every group that night. Maintenance and operation, safety and lighting, and waterfront access came second to reliability; preserving views, look and feel, recreation, and amenities came in last in the scale of values these New Yorkers would prioritize.

We wondered what makes one group value reliability over looks or vice versa. Differences in income, geography, and their experiences during disastrous events such as Sandy could be factors. Nevertheless, the fact that each community responded to the activities in different ways drives home the importance of having opportunities like this to assess public opinion. The needs and desires of adjacent populations can be distinctly different, meaning one-size-fits-all solutions can fail to mesh with the daily urban fabric. It is now up to the LMCR team to create solutions that reflect the public interest at the local level, while providing security for Lower Manhattan as a whole.

Our take

These two hour kickoff meetings promised to be the first of many encounters that will allow residents to see and react to possible flooding solutions before final designs are selected. If you live in the area, but do not know much about OneNYC do not let this prevent you from attending the next meetings. You will find that facilitators will share a great deal of information to help you understand the issue. History of the development of the project and about each neighborhood, funding efforts, and partnerships were all covered.

It was a relief to hear that others groups besides LMCR are working around this issue, they acknowledge the existence of each other, and the importance of working together. How will they share resources and not duplicate efforts? This was left unclear.

It is understandable that, given the scale of this project, there was a lot of information to talk about in a short time. This may have been an issue for some participants, but in no way prevented them from speaking up in the small group discussions. In order for this event to be accessible for more people translation in Mandarin, Cantonese, and Spanish was available.

Seawall design was one of the main topics during the small group discussion. Climate Central research indicates that the US has seen more than a doubling in flooding due to global warming caused sea level rise. Recent events back this up. Seawalls are important components of initial adaptation efforts, but they are not a long term solution. In future meetings we would like to hear about mitigation and remediation strategies that help reduce global warming and offer a chance to slow down the rise of the oceans. Some of the methods can be done at the individual level, such as reducing energy consumption and air travel. If such strategies are not in place, we can only expect to need higher and higher walls every couple of decades, which eventually will not be enough to protect coastal life, infrastructure, or ecosystems.