In New York City, most of us live in apartments, making it impossible to power our homes from our own set of solar panels. But that’s about to change. Susanna De Martino explains:

On July 16th, the New York State Public Service Commission approved a landmark set of rules to give renters, low income residents, and people who don’t have access to a building’s rooftop a way to benefit from solar energy. The state’s new Shared Renewables Program will encourage development of shared solar gardens, which can be used to meet consumers’ energy needs through a net metering system. Customers participating in the program will get a credit on their utility bill when energy is produced from solar panels they are subscribed to—even if those panels aren’t on their own roofs.

The new program is part of an overall energy strategy, titled Reforming the Energy Vision (REV), that aims to transform the way power is produced and distributed across the state, by adding renewable sources and making a more resilient, decentralized electrical grid.

Solar One recently held a celebration of the Shared Renewables Program with leaders involved in the new policies including Audrey Zibelman, the Chair of the New York State Public Service Commission, John Rhodes, the President and CEO of NYSERDA, New York State Assemblywoman Amy Paulin, and New York State Senator Kevin Parker.

Speakers at the event emphasized the importance of building an electrical system that is more affordable and efficient and gives customers more control, and noted that the Shared Renewables program is a big step in that direction. According to Ryan Chavez, the Infrastructure Coordinator of UPROSE (a community health and resiliency organization based in Sunset Park, Brooklyn) “low income communities and communities of color are on the front line of climate crisis. They contribute least to the problem and receive most of the burdens.” Chavez praised the impact of the Shared Renewables Program for low-income communities like Sunset Park.

Richard Kauffman, the Chairman of Energy and Finance for New York in the Cuomo Administration, also praised the program—and the Cuomo administration’s general larger push for solar power—by emphasizing the numbers: solar growth is up 300% from 2011 to 2014 in New York State, and has created 7,500 jobs.

Providing easier access to solar power for apartment dwellers and retail businesses is likely to speed the growth of solar installations in the five boroughs. In the industry journal Utility Dive, proponent Sean Garren points out that “New York City is a shining example of people who would want to go solar but can’t put it on their roof.”

The New York State government’s moves toward solar energy are also part of a broader political trend focusing on solar/renewable power as a poll-friendly response to the nation’s energy woes. Hillary Clinton’s recently unveiled environmental policy for her 2016 presidential bid focuses on solar power, and support for renewable energy is growing among independents and some Republicans as well.

The growing interest in solar is a good sign that politicians and the public are beginning to face up to the technical challenge of climate change. But to put these new plans in context, the huge task of replacing fossil fuels at adequate speed is explained by climate journalist Eric Holthaus in a Slate piece critiquing the Clinton campaign’s proposal:

Although solar often gets top billing in political announcements like Clinton’s, it still represents less than 1 percent of our electricity generation, so it will take tremendous growth for many years for it to provide a meaningful offset to fossil fuels. Despite its sexiness, solar is among the most expensive ways to decrease our country’s carbon footprint. A far better near-term choice is wind power, but both wind and solar begin to have another problem at scales at or above that which Clinton is discussing: Since solar panels and wind turbines can’t currently work at full capacity 24 hours a day, they require huge advances in energy storage and grid capacity, as well.

Some think that limiting energy solutions to renewable sources only—like wind and solar—may be counterproductive. A detailed Mother Jones piece, “Why We Need Nuclear Power,” looks at the pros and cons of our energy choices. The key issue with planning an energy system based entirely—or mostly—on renewables is energy storage for times when the sun isn’t shining or there isn’t wind.

Storage methods are costly to build and need to have huge capacity in a renewable-only scheme; soon, we would would need enough energy storage to run our society, since solving climate change also means switching to electricity for every purpose now relying on fossil fuel, including powering our transport and providing building heat. According to Armond Cohen, executive director of the Clean Air Task force, “What people really miss about storage is it’s not just a daily storage problem. Wind and solar availability around the world, from week to week and month to month, can vary up to a factor of five or six.”

Until the problem of storage is solved—by building storage methods and a new power grid compatible with all-renewable energy—solar and wind will have to fall back on natural gas turbines when energy production is low. Many climatologists stress, therefore, the importance of multiple options when building a no-carbon energy system. Nuclear has advantages: for example, its capacity factor (meaning how much a generating plant delivers of its maximum capacity) in 2014 was 91.8, while wind and solar’s capacity factors are less than half as large. And nuclear power runs 24/7, 365 days a year.

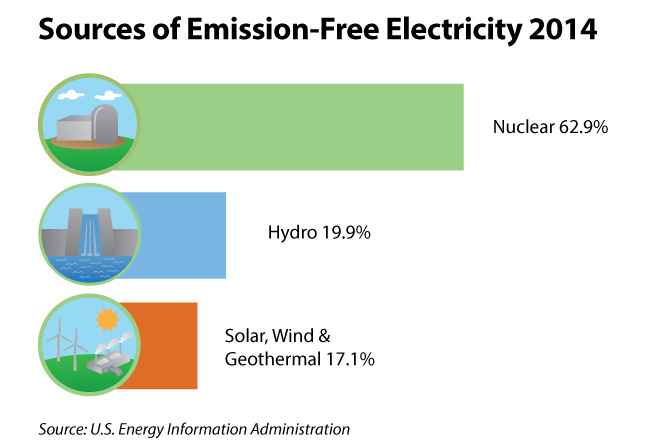

New, very tall wind turbines reach steadier wind at a higher altitude and may soon achieve 65% capacity, which would be a big step forward. But as shown in a piece from the Nuclear Energy Institute, in 2014 America’s nuclear plants still generated more than double the clean energy provided by wind and solar combined.

How much carbon-free energy does the world need? Nathan Lewis, a solar energy researcher at the California Institute of Technology, estimates the equivalent of 10,000 nuclear reactors as the minimum to power the global economy in 2050, at which point we should be almost entirely off of burning fossil fuel in order to prevent the worst effects of climate change. The world, at present, has 439 reactors. More than 80% of the world’s energy still comes from fossil fuels, and energy demand is growing.

Nuclear power faces strong social resistance because of rare but frightening accidents, though building power plants is safer now than ever before, and nuclear plants have a significantly smaller land-use footprint than the massive amount of solar panels that would be necessary for all renewable energy. But political realities have given solar today’s moment in the sun with politicians.

As Susanna De Martino’s report points out, the challenge of climate change is ultimately about how we produce and use energy. David Ropeik, who studies how risk is perceived, marks the EPA’s Clean Power Plan as a new sign that the national conversation has irrevocably moved forward into a productive phase focusing on solutions. The Shared Renewables Program also shows significant progress can be made quickly.

But in terms of climate and impacts, we’re on nature’s timetable, not our own, and not that of the political system.

In the same month the Cuomo Administration announced the Shared Renewables Program, aimed at reducing carbon emissions, the administration also announced plans for a $4 billion overhaul of LaGuardia Airport. The overhaul would modernize the overcrowded terminals and facilitate entry to New York by air for decades to come. The unmentioned price tag of modernizing LaGuardia: air travel is among the fastest growing sectors of carbon emissions in the global economy.

New York City, the destination served by LaGuardia, may need climate to stabilize at or below 2°C to be safe over coming decades, but the 2°C target is already viewed as very challenging to achieve — unless we figure out a way to precipitously drop global carbon emissions.

Lighting off tons of aviation fuel while accelerating off a runway at LaGuardia is not a process that assures the future of New York City; the heat generated by the engine on takeoff is surpassed within months by the secondary heating from greenhouse effects of the gases released. Over years and decades, the continued daily heating from the insulating effect of the gases from a single LaGuardia takeoff will incrementally add to sea level rise, both through direct expansion of the warmer oceans, and through the melting of polar ice sheets. The net result of our cumulative fossil fuel use is a map of New York that looks like this, conditions that are expected to be economically catastrophic for New York State.

Future posts on City Atlas will explore solutions that could make New York City and New York State better prepared for a zero carbon future. To use the $4 billion LaGuardia overhaul as an case study for new ideas: perhaps $3 billion could renovate the airport, and $1 billion could launch a consortium at Brooklyn Navy Yard tasked with positioning New York once again as one of the world’s leading shipbuilding and passenger ports. New York City will remain an international destination; tourism is central to the economy, and a multicultural city needs access to the world for its own citizens. Re-creating low-carbon intercontinental travel by ship, for those who can afford the time and can step back from the carbon intensity of air travel, could be one way to insure the continued prosperity of the city, and establish New York as again a leading manufacturing center for new technology. We have a big challenge, and we have to get used to thinking big. Perhaps it’s better in the long run to ditch our third airport entirely, build zero carbon ships, and not rely on building new levees around the city as a questionable attempt to hold back the sea.

Three short videos below give expert perspectives on the situation:

- The difficulty of achieving the 2°C target without abrupt decarbonization, beginning immediately.

- The nature of global energy demand, which for now is still concentrated in wealthy countries.

- A review of ideas for how a low carbon society might work.

Angela Druckman – Low Carbon Fun: Lifestyles in a Low Emissions Society from tyndallcentre on Vimeo.