Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail has revealed a vast new sustainability plan, budgeted at $7B, being prepared by the provincial government of Ontario. The Globe and Mail quotes Kathleen Wynn, Premier:

“We are on the cusp of a once-in-a-lifetime transformation. It’s a transformation of how we look at our planet and the impact we have on it. It’s a transformation that will forever change how we live, work, play and move.”

The Ontario plan includes 80 initiatives that remove fossil fuels from daily life, and is meant to be enacted between 2017 and 2021.

Here in New York City, the same climate science is understood by government, and the initial steps of ambitious plans are underway. But work towards the goals is largely still building by building, in conversations between architects, owners, the City, and developers. Earlier this year, Angie Koo went to an energy town hall to learn more:

Which apartment building is more energy efficient to heat: a complex designed in 1948 and built in 1961 in Peter Cooper Village/Stuyvesant Town, with master metering for heat and electricity, or the Solaire, the first gold LEED-partnered building in the U.S., built in 2004?

Andy Padian, Founder and President at Padian NYC Consulting, posed this question to the audience at an Energy Town Hall at the Lenox Hill Neighborhood House on the Upper East Side. The answer will be revealed later on, and it may surprise you. In many ways this comparison, between old and new, and traditional and innovative, framed the challenges discussed in the town hall itself.

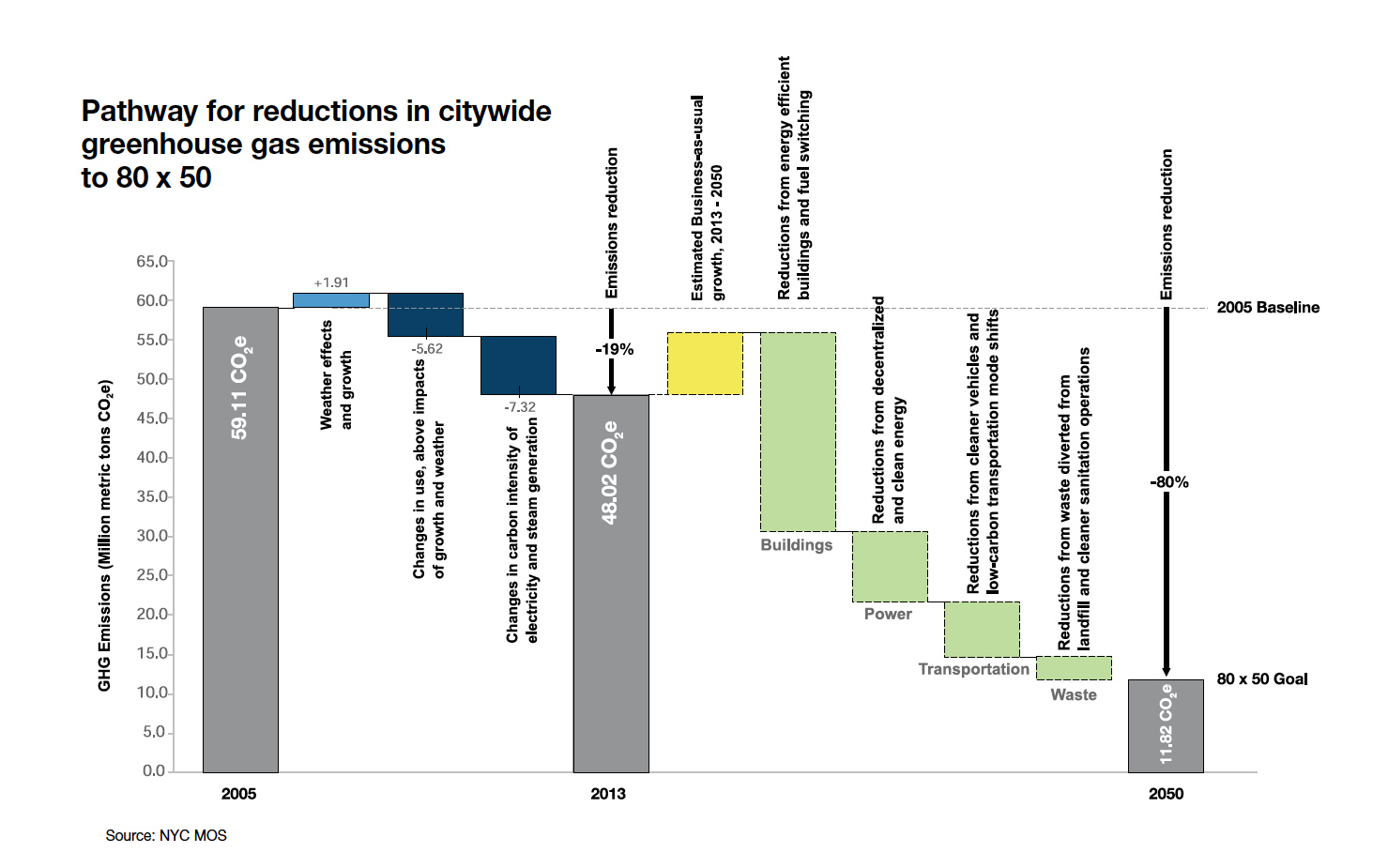

The backdrop to the town hall could be summed up by Mayor de Blasio’s call to arms in the “One City Built to Last” initiative launched in 2014, which aims to reduce carbon emissions 80% by 2050:

Global climate change is the challenge of our generation…New Yorkers will rise to the challenge. We will build on progress we have made to become more resilient to a changing climate and to mitigate the harmful greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change. We are committing to reduce our emissions by 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2050, making us the largest city in the world to commit to this goal.

The town hall event, one small front in an ongoing challenge for the city, was moderated by Ken Gale, host of WBAI’s Environmental show Eco-Logic. Guest speakers Padian and Chris Benedict spoke to a captivated audience of about 50 local apartment owners and tenants about how their homes can become more energy efficient, and in doing so, save them money. Also among the participants and attendees was the New York City Safe Energy Campaign (NYCSEC), passing out leaflets advocating for the closing of Indian Point nuclear plant.

Padian’s expertise on building science was on display as he ran through what appliances should be retrofitted in homes and how attendees should change how they interact with their space and technology. He points to lighting as the most important feature to modify within homes, as we’ve moved from incandescent to fluorescent, and now to LEDs, best of all, and which are dropping rapidly in price.

Then, the basics: our parents have likely reminded us a countless number of times to turn off the lights if you’re not in the room. Growing up, our parents likely didn’t have access to the smartphones with timer apps, motion sensors, or smart power strips that add options to controlling lights and appliances – easier, or more complicated, depending on your perspective.

Padian reminded the audience that television cable boxes consume the same amount of energy regardless of whether the TV is on or off. The only way to cut this energy consumption is to cut the power to the cable box every time we want to turn off the TV, and a power strip does the trick. And as you replace major appliances, choose the highest Energy Star efficiency rating.

In practice, making multiple, careful changes to lighting and water, replacing inefficient heating systems, air sealing windows, switching from master metering to sub-metering, and other internal changes have led to significant savings, reduction in energy consumption, and reduced vacancy rates in housing developments. Padian also remarks that the energy savings that could be made through these methods would reduce reliance on the Indian Point nuclear plant, to the point that its operation is may longer be necessary.

Whether our energy grid should include nuclear, either from existing plants or new designs, in a mix with wind and solar, is a subject for a future City Atlas piece. But whatever the zero carbon solution, curbing the growth in our power demand is a far cleaner and more effective solution than attempting to build more supply. The cleanest, and most economical, power station is the one that is not built.

Council Member Ben Kallos and Senator Liz Krueger made brief appearances midway through the town hall, speaking about the alternative energy developments underway in the city and their 80% renewable goal by 2050 while calling on Mayor de Blasio to aim for 100% renewable. The audience cheered and clapped as Kallos and Krueger mentioned the ban on fracking at the state level, expanding solar to tie into grids and cars, developing offshore wind in Long Island and Coney Island, and getting the governor onboard with the closing of Indian Point. They closed out with an impromptu rendition of “Blowin in the Wind”, marking the end of the halftime show of the town hall.

Chris Benedict, a practicing architect heavily involved in passive housing, picks up where Andy Padian leaves off, with a focus on the external facade of the building. She aims to create a culture of resilience through the synergy of managing air, water, vapor, heat, and light.

The Passive House movement has its roots in Illinois in the 1970s when scientists created a self-regulated heated home, whereby the structure loses heat in equilibrium with the heat generated by the people inside, negating the need for additional heating fixtures. The concept was met with little fanfare in the States, but it was picked up in Germany where it was widely executed. The movement then found its way back to the U.S. where it is currently gaining momentum and lauded for its energy efficiency gains.

In practice, Chris Benedict uses a method that layers foam insulation over the cement blocks of a building structure, and then brick over the foam insulation. These layers trap heat and prevent the air leaks that traditional buildings are prone to. She explains that in essence, it is like putting a sweater over a building. Only buildings that pass a de-pressurization test that checks for air leakage can be certified as a passive house. Ultimately, these buildings use roughly only 20% of the energy of comparable structures. Benedict’s design at 803 Knickerbocker Avenue, in Bushwick, has been featured in the New York Times and is used as an example in the “One City Built to Last” plan for the future of New York’s buildings.

Part of the challenge of applying Passive House methods to buildings more widely is that, up until recently, it was against the law to do so to existing buildings. A change in code has made it possible for individuals to add up to eight inches of insulation to an existing facade. This opens up a world of possibilities as Benedict and other architects move to develop more passive houses and retrofit older complexes. Particularly, Benedict spoke excitedly about the potential to renovate mechanical systems from the outside, such as with energy recovery systems and heating and air conditioning systems, to add efficiency without compromising the interiors of people’s homes.

Returning to Andy Padian’s question from the beginning of the town hall, which building do you think is more energy efficient?

If you answered the 55 year old building in Peter Cooper Village/Stuyvesant Town, you would be correct. In fact, buildings in Peter Cooper Village require one-third less energy to heat than the Solaire. Padian admits that the comparison is not completely fair: the Solaire has central ventilation and fans that run 24/7 to remove heat, amenities that add to power usage. But the point it drives home is effective. It is not always the flashy, new ideas or developments that are most suitable for the task at hand, retrofitting and rethinking older and existing structures is just as necessary, if not more so.

The inner workings of our homes and appliances appear seemingly divorced from the conversations of global energy sustainability where the big headlining rockstars are solar, wind, hydro, biogas, and so forth as brought up by Council Member Kallos and Senator Krueger. Yet, we live in a world of existing infrastructure, and emission targets and energy goals must take that into account. Were we to re-imagine our cities from scratch, it is easy to find ways to only depend on renewable energy without removing fossil fuels from the earth and to build in environmentally sustainable ways with the best technologies and materials. But we inherit our cities; we have a legacy building stock that only turns over slowly, across many decades. (As Joel Towers, Dean of the New School/Parsons School for Design and an architect himself, told us in his interview in City Atlas, New York City’s replacement rate of buildings is one or two percent per year, meaning likely more than 80% of our current structures will be still here and in use in twenty years time. 2036 may look a lot like today, in other words.)

To begin moving towards sustainability, we need to first become energy efficient with what we have in our homes and neighborhoods. Innovations in renewable energies will be that much more potent in the future if we can reduce our energy consumption now.

Addenda:

Chris Benedict has a concept for modernizing New York’s building code that is ingenious in its simplicity. Rather than writing (and regulating) dozens of rules for every type of material or method that produces sustainable structures, why not simply shrink the size of maximum permissible heating and cooling devices, in proportion to the total square footage of the building? It’s the energy consumed by these devices, after all, that we are trying to conserve, and the smaller they can be (and still serve the building) the better.

That would pull all new buildings towards Passive House standards, as they have naturally have smaller heating and cooling demands.

Logically enough, this is called “The Perfect Code” (described here), and in a sign of how the life of a New York architect revolves around the mysteries of the Building Department, Benedict even explains it in a one act play (presented by architects not actors).

The de Blasio Administration has two excellent and very readable plans online that delineate the importance of building efficiency to the city’s future.

From One City, Built to Last, a 100 page guide to current initiatives and ideas for the future, comes the following summary:

Under an 80 by 50 scenario, our aging buildings will need to be transformed into highly energy efficient structures and powered by renewable sources of energy, and new buildings will need to meet the highest possible energy performance standards. All buildings would need to significantly increase the insulation of their exterior walls, roofs, and windows. Buildings would also need correctly-sized and energy efficient heating and cooling systems, and must install high efficiency lighting and appliances. Heating and cooling equipment must also be operated by personnel trained in energy efficiency best practices, and residents would need to make changes to their everyday behavior to conscientiously conserve energy. Eventually, all buildings would also need to move towards low-carbon and renewable sources of energy and advanced energy recovery systems.

And from One NYC, the City’s overall climate strategy document, you can see the dominant role of building efficiency:

Photo: “Energy heroes? Here in NYC: Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village” (Taken from: Wikipedia)