From one perspective, New York City really is an amazing machine.

For a population of eight million, every day, electricity, clean water, and transportation are supplied, and waste is taken away — largely without our attention, except when the train is slow, or the city beaches close after a heavy rainstorm. Or, in the case of Sandy, when the entire system shuts down from flooding, except for the miraculous century-old water supply.

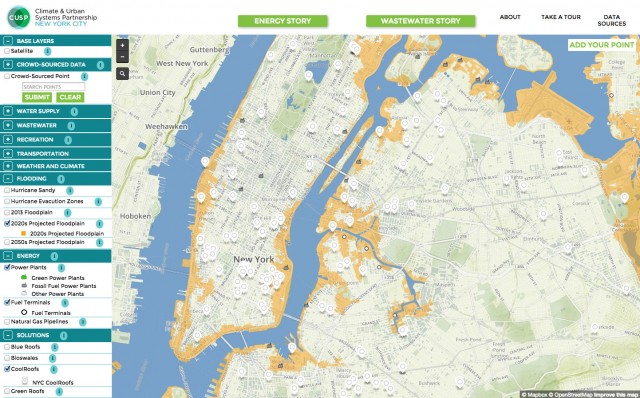

A new online map shows some important features of the city and describes how we can respond to changing climate. The project developers are a science team called the Climate Urban Systems Partnership, working under an NSF grant:

“The Climate & Urban Systems Partnership (CUSP) is a group of informal science educators, climate scientists, and learning scientists in four Northeast U.S. cities (Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, New York City, and Washington, DC.), funded by the National Science Foundation to explore innovative ways to engage city residents in climate change issues.”

Maps for Pittsburgh and New York launched earlier this year. In our city, the New York Hall of Science in Queens is the partner institution for CUSP. Chiara Zaccheo sat down with Dustin Growick, the first educator attached to the project.

New York’s CUSP map serves as an online hub and digital platform for individuals and communities in New York City to come together and share data, information, stories and visualize the changes related to climate happening in our neighborhoods.

Climate change is both a threat and an opportunity for people to engage with their city, and the CUSP map demonstrates this link. I sat down with Dustin Growick, a Science Instructor at the New York Hall of Science to learn more about this exciting new resource for New Yorkers:

What is the CUSP Map?

The CUSP Map is an interactive digital toolkit. The CUSP Map gives people and the different organizations working under the umbrella of climate change a place to really start a discussion about the ways in which climate change already is, and will continue to impact, New York City, the activities we love, and specifically, the city’s systems upon which we rely.

The idea is to have a marketplace for people to share questions, ideas, conversations, programming – events that are happening – that have something to do with climate change. To really drive home the point that when we think about climate change as New Yorkers, it’s not really about a polar bear on a ice floe up in the Arctic, it’s about the way that more severe storms are going to impact the city with effects like flooding, combined sewage overflow, and things like that.

At the launch event it was said that CUSP education starts with someone’s passion. Can you expand on that idea?

Anything you can key as far as personal relevance is going to resonate with people. It goes back to – if I tell you we have to do something about climate change because there is this polar bear thousands of miles away – while some people might have some very hard, fast feelings about environmental conservation or endangered species, that might not resonate with them immediately. Someone who just enjoys biking in the city might not be concerned with things happening thousands of miles away.

But if we step back we can talk about how the warmer our planet gets, the more moisture is going to be available in our atmosphere, we’re going to get stronger and more severe storms as we have started to see over the past couple of years, which is probably going to lead, as we’ve seen, to more flooding in our streets, more sewage being combined with water overflow that then is pumped into our waterways.

So, CUSP education is showing people the ways in which climate change connects to things that they are passionate about.

When and how was the need for the CUSP map identified? What gap are you aiming to fill?

I think the major gap we are aiming to fill is that middle ground between people who have a hundred percent buy-in – who recognize that climate change is an issue and recognize how, where, and why it is affecting our city – and people who know kind of nebulously this is an issue and it is going to continue to affect us but aren’t exactly sure in what way it will affect the city. And even more importantly, it’s for people who want to know the ways they can get involved.

We hear the science about climate change a lot…but you know, if I’m a mom of two living in Woodside, Queens: ‘A’ – how does climate change specifically affect me? and ‘B’ – what can I do personally to either help, get involved, spread the word, or what can I do as a homeowner, an apartment owner, to help try to mitigate this problem?

By definition it is a global issue. So I think it is very easy for people to think of it as large and abstract, and what we are trying to do is try to bring it home to the personally relevant level.

What was the biggest surprise for you when you put together the data?

There was so much out there. It is hard to figure out what exactly is really good and necessary, and will help people understand and visualize the problem, as well as what is almost…too much.

I think that is something scientists do a lot when we talk about models, modeling different complex systems. There is tons of data out there but how do you boil that down to the most important points that are going to resonate with people and help them understand the broader issue without feeling overwhelmed by information?

I was unaware of how water runoff from severe storms can lead to overflow into our waterways. The way combined sewage overflows work is we have the same piping system for sewage as we do for water runoff and storms. From a moderately or meager rainfall they do not mix, and the treatment system can handle the amount of water, but when it is extreme, a lot of rain fast, the system is such that the storm runoff mixes with sewage [and is released untreated into waterways].

That’s where you get the term combined-sewage overflow. There are dozens of combined-sewage overflow pipes along the Hudson River, Jamaica Bay, and the East River.

On the CUSP map you can turn that layer on and see how close you might live to one. It is maybe the spot you do not want to be swimming in the day after a severe storm.

What were some of the challenges of putting together the data?

Figuring out what kind of data we wanted to use and figure out exactly what would resonate with people, and the best way to display it. One challenge we had is that to get something like this rolling, we needed personal relevancy, and we talked about the idea of once you land on the map, you could zoom straight to your neighborhood and immediately see what is going on in your neighborhood – the immediate impacts.

But this is supposed to be a citizen science map, where people load their own information, so when you first start using it there is not a lot on the map. So it is kind of a challenge to see where on the map we wanted to start, before there is much data on the map.

What is an exciting feature that the CUSP map offers that new users might not know about or is not obvious when first using the map?

Two things: first, it is geared for people to add to the map, to add their story of climate change in the city. Users can add their own data points, whether it is an observation you made or some infrastructure project you see going on in your neighborhood that allows people to fill in the gaps that we have in the data.

DEP does not have a full map of their bioswales, which are basically sidewalk plantings that allow for drainage water to be absorbed and prevent streets from flooding. We can use this tool as a place for people to make observations and see those, and start filling in the map.

We can actually have a full map of all the different types of green infrastructure throughout our city.

Second, you can see future flooding and storm projections of where sea level rise may be in ten, twenty, fifty years. Even more important for the next couple years is where flooding is going to occur during the next storm. Users can turn on the Sandy flooding layer and see how far inland flooding occurred during Hurricane Sandy, and there are projections on how far flooding could occur during the next hurricane.

This is immediately applicable for you if you live in Jamaica Bay, for instance, or near a lot of low-lying highways.

What do CUSP and its partners plan to do with the stories, videos, pictures, and data related to climate change that New Yorkers upload to the map?

We hope that people start to see climate change more as something that is affecting us globally as well as locally. An additional benefit is that we have brought together small organizations working in different parts of New York City, with often overlapping missions, that may have never otherwise come into contact with each other, and that may have programs that tie in really well. This way we can get the word out to a larger audience about the work that they do.

We like to think of CUSP not as a large project that is run by a specific person. The ‘P’ stands for partnership. We try to get as many of those local, smaller organizations together and see it as the whole is better than the sum of its parts.

Is there a specific story that comes to mind that has been uploaded on the CUSP map and stuck out to you?

There have been a couple of points uploaded by people showing severe flooding on the highways – places that used to not flood after storms that are beginning to flood. Not only does that show me how it affects someone trying to get to work and commuting but ultimately the idea is to share these data points with the City to show where the places are that have issues that need to be addressed.

Is there a CUSP map application (app) being developed?

We do not have an app yet. Right now the interface works relatively well on an iPhone. We are thinking about making a mobile version so that it is a little more stable. On your iPhone it does look fine, it isn’t perfect, but you can add your data points and upload your data. As this is a program where we want people to make specific observations out in the field of New York City, I think it would be very helpful to have an easy interface in your hand.

Coming back to the concept of neighborhoods and communities sharing information, why is that especially important in facing climate change?

It is important for any issue. You have to make it personally relevant – the way it affects people’s lives on a day-to-day basis.

The ultimate goal of the CUSP map project is to help bring climate change to a personal level to get people thinking about and involved with the science of climate change – how it will affect us and our lives here in New York City.

In addition to that, we are already seeing the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) look at our map to see different features of our green infrastructure data set. We are seeing the White Roof Project use the map as a place for people to upload white roofs throughout the city.

The City itself does not know how many white, blue, and green roofs there are in the city. This is a great way to fill in the gaps in the data from a lot of different organizations. The City moving forward is thinking more and more about how do we implement more green infrastructure projects and get the city ready. The fuller the picture you’re looking at when making those decisions, the better the planning.

How can New Yorkers get involved and spread the word, and along the same lines, how is CUSP reaching out to individuals in New York?

Individuals can become involved simply by using the map, by uploading programs, events, and mapping observations in their neighborhood.

There are already a lot of data points showing events and programming happening through our different partners. So if you are curious about what is being done or what programs or events are happening with respect to climate change in DUMBO, for instance, you can go on the map, find that area, and click on the data points and see what people in your area are concerned about and what events are happening.

The lead partner for CUSP is the New York Hall of Science partners who are doing awesome work as it is, to help them get the work that they are doing out there, but also starting a conversation between us, between them, and other partners who are working on similar projects. A more collective power is going to be better than a bunch of individual units trying to exact change on small neighborhood scales.

Say a New Yorker looks at the map and sees the projections for 2020 are that her subway line might be heavily flooded during the next storm – this is important information to know and to prepare for, but how can she turn this information into a positive action?

CUSP and all of our partners in New York have programs that are listed. A lot of these programs are about how you get the conversation starting with the people that matter, as far as decision-making goes. The more of us that aware of information, who to get in contact and how to talk to them about the issue, the BETTER. And the more likely we are to be able to address that issue. So if it is talking to your local representative or knowing how to go about reaching and contacting the MTA for instance, that is a great thing.

We talk a lot in our workshops about the language of climate change and how to talk about this problem in ways that resonate, in ways that will help to enact change both on the neighborhood level and the city level.

One of the other things that we are working on with different organizations is to design workshops, festivals, and outreach kits – so that if you are an organization that does an environmental festival or you go to schools, we help to design hands-on interactive workshop festival kits so that people will actually have a tangible way to understand the problem.

We have a kit that models the way that extreme storms are affecting our city and we have one that models the hidden [carbon] costs of certain types of food versus others. We have workshops about how you design and facilitate engaging, hands-on experiences that try show people the ways their lives are being affected in a much more fun, hands-on interactive way versus for instance a video or some sort of scary monologue.

Is there anything else you would like to share about the CUSP map?

It just came out of beta mode, so we have been working on getting it functionally right for almost a year now. We are excited to see the ways in which people and organizations use it. Everyday when I open the map and see more data points, that’s a good thing! There are more and more data points being added every day, and there are more and more people concerned about the issue and wanting to contribute to the conversation. We started CUSP because we wanted to start a conversation that mattered to New Yorkers.

Take a tour of the CUSP map:

Top photo: Todd Narasuwan/nysci.org