The third in our series of summaries of the city’s plan for the future, the SIRR.

Soon after Hurricane Sandy, photographer Iwan Baan chartered a helicopter to do a portrait of the struggling city for New York Magazine. The photo reveals the city’s downtown completely blacked out, surrounded by perfectly black waters and, beyond 34th street, a sea of lights. This image captured an international fear: if a storm could shut down New York—the city that never sleeps—a storm could bring down any city in the world.

Lower Manhattan, containing Wall Street, the stock exchange, the World Financial Center complex and Goldman Sachs, still represents the heart of the financial industry, though most major banks are now headquartered in midtown. Combined with the luxury neighborhoods of Tribeca and Soho, Lower Manhattan is a familiar hub around which much of the wealth of the world revolves. This patch of historic land is also surrounded on three sides by water.

Areas in New York City’s other boroughs suffered equal, or more brutal, direct consequences from Hurricane Sandy (most fatalities from the storm were in Staten Island, and there were more damaged homes and displaced residents in Brooklyn and Queens), but the visual impact of a darkened Manhattan captured the imagination. Human suffering around Manhattan was real and profound as well; apartment houses in the Financial District, Chinatown and the Lower East Side had thousands of stranded residents, including many elderly without power, water or elevators; dozens of businesses around Southern Manhattan, including those in the South Street Seaport on the east and Chelsea on the west, were inundated and destroyed.

For the purposes of the Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency (SIRR) report, Southern Manhattan goes beyond Wall Street and includes all the vulnerable “areas along the coastal edges of Manhattan” up to 42nd street, including parts of Chinatown, the Lower East Side, Stuyvesant Town, Kips Bay, Tribeca, the West Village, Chelsea, and Hudson Yards. Along the East River shore of Manhattan is ‘hospital row,’ and an essential story in the days and weeks after the storm was how much damage there was to the city’s primary emergency care facility, Bellevue, and to NYU Medical Center, both of which were forced to evacuate their patients during and after the storm; New York Downtown Hospital and the Veterans Administration Hospital on East 23rd Street evacuated prior to the storm’s arrival.

The tip of lower Manhattan is where the city was founded in 1624, and from which it grew north. Early maritime activity lead to thousands of wharves and docks; almost from the start, the new city began expanding the coastline to create more buildable land. Over 900 acres were added to the natural coast of Southern Manhattan—over 40 percent of the current land area on the SIRR map of the section. Although most of the maritime infrastructure of piers and warehouses fell into decay after World War II, urban renewal led to new office, residential, and park developments along Southern Manhattan’s waterfront, much of it on this extended shoreline.

Socioeconomically, the area contains a multitude of different people and cultures, living in a wide variety of conditions. 24 public housing developments, containing over 15,000 units, are located in this region. The Lower East Side and Chinatown are the densest and most populous neighborhoods, but also have the highest poverty rates, almost double the New York City average. In contrast, neighborhoods like Battery Park City and Tribeca are extremely wealthy, with poverty rates less than half the New York City average.

Although the region was severely impacted by the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the financial crisis of 2008, Lower Manhattan remains a vital economic hub. And, even though Fortune 500 companies and Wall Street get the most publicity, Lower Manhattan contains a multitude of different businesses, including nonprofits. Over 83% of Lower Manhattan’s businesses have less than 10 employees. The only exception to Lower Manhattan’s economic resiliency is the eastern edge of Southern Manhattan, which lacks the dynamism of other neighborhoods in Lower Manhattan and has rising office vacancies.

Southern Manhattan is a nexus of the City’s infrastructure; as floodwaters hit, damage rippled out across the entire city. Two of Con Edison’s major electrical substations are located in the floodplain near the East Side Drive. Four of New York City’s hospitals—20 percent of Manhattan’s total capacity—are located in floodplain along the East River. Two major wastewater facilities are located along Canal Street. Important data and telecommunications lines run through the district, as well as major roads and tunnels such as the Holland Tunnel and the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel. And, last but not least, the subways: 12 different lines stop at 17 stations in Southern Manhattan.

What happened during Sandy, and risks in the future:

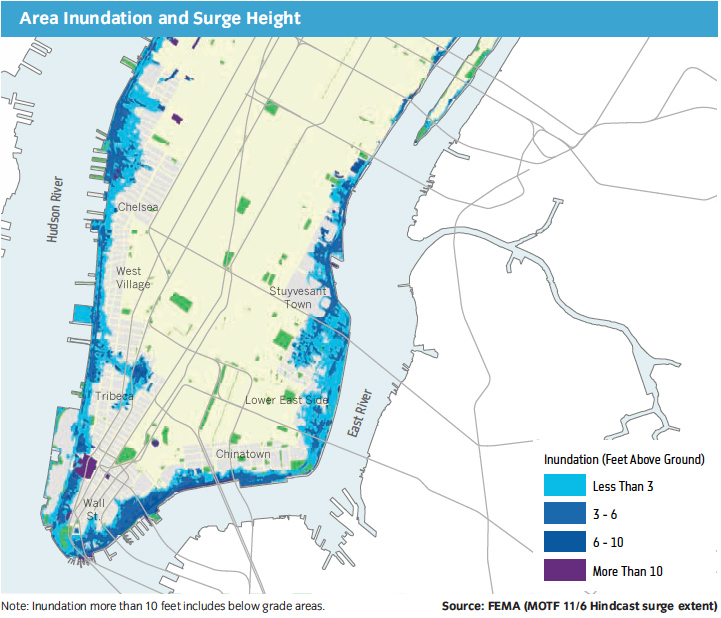

Due to its extremely low-lying coastal edge, Lower Manhattan remains vulnerable to the sea. When Hurricane Sandy hit, floodwaters overwhelmed bulkheads and surged one or two blocks inland. Areas that had been built on landfill extending the natural coast were most heavily damaged by the storm surge. Fortunately, because most buildings in Lower Manhattan were built with concrete, steel, or stone, buildings did not collapse in the path of the incoming flood. (One old four story building in the West Village lost the facade during the winds prior to the flood.) The major damage came as critical infrastructure, communications, power, and supplies stored at ground level were destroyed by exposure to seawater.

As Ivan Baan captured in his photograph, the most significant impact of Hurricane Sandy in Lower Manhattan was the power outage that occurred across most of Manhattan south of 34th Street; a primary cause was the explosion of the flooded Con Ed substation on 14th Street and Avenue D. Although few buildings were structurally unsound, most residents were left without power and water. Elevators shut down in high-rises, making it almost impossible for old and infirm people to get out of their apartments. Water damaged telecommunication networks, so internet and phone systems failed. It took four days for power to be restored after the storm.

Unlike most of the region, Southern Manhattan’s hospitals attempted to prepare for the storm by evacuating some patients or installing special generators. Unfortunately, no facilities were fully prepared for the extent of the power outage and storm surge. Fuel supplies for generators were located in basements that flooded. As critical building functions failed, all four of the hospitals in the area covered by the SIRR report were forced to evacuate by the end of Hurricane Sandy.

The many tunnels that run under Southern Manhattan were flooded, including the subway system.

Although service to many of the subway tunnels resumed within a few days after the storm, the tunnels that crossed the rivers took much longer to clear. The MTA’s new South Ferry Station (hosting the 1, with a connection to the R at Whitehall) opened to the public in 2009 at a cost of $545 billion, and was built with 9/11 recovery funds; the station was entirely flooded by Sandy. While renovation takes place, the MTA has switched trains back to the old station; the rebuilt station is expected to be complete in 2016, at a cost of $600 billion. (This station may be the single largest repair bill from Sandy.) A large mosaic in the South Ferry Station, by artists Doug and Mike Starn, survived the storm.

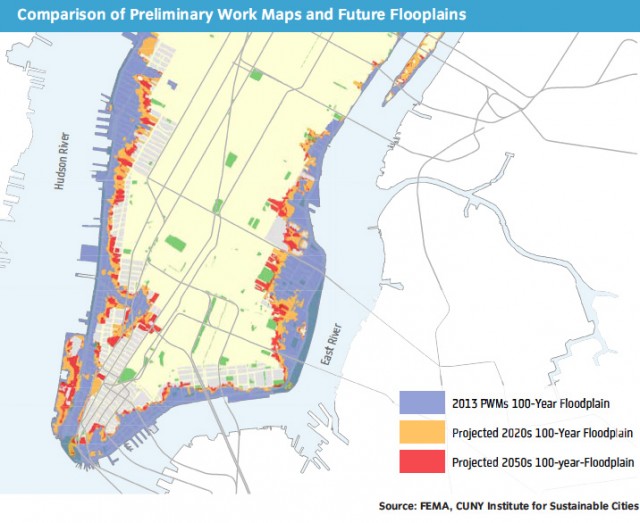

As climate change continues and the sea level rises, more areas will become susceptible to flooding on a frequent basis. As FEMA expands their projected floodplain in 2013, the number of at-risk buildings in Lower Manhattan increases 73%. This risk does not even account for the rising sea levels. For more on predictions of sea level and the waterfront, see the tool created by Climate Central before Sandy, and our interview with scientist Klaus Jacob, after Sandy.

Most of the initiatives for Southern Manhattan emphasize hardening and protecting assets along the waterfront, and building resilient features into essential infrastructure and services. Two that stand out are the use of removable flood walls for the low-lying shores along the east side and west side, and the proposed construction of a levee at South Street, that would extend land on the island’s edge and provide a barrier to future storm surges. The cost of the construction is intended to be offset by new residential and commercial development atop the levee (Seaport City). There is a related interview with Daniel Zarrilli, NYC Director of Resiliency, at the Next City website. Our full review of the initatives follows.

Initiatives:

Coastal Protection

Coastal Protection Initiative 6: Raise bulkheads and other shoreline structures in areas most at risk of flooding. (2013)

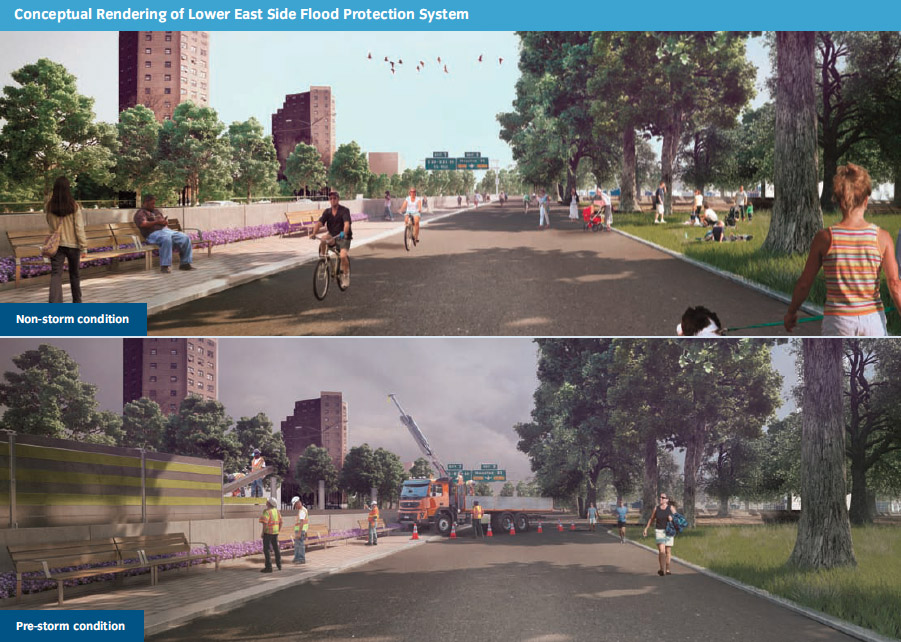

Coastal Protection Initiative 21: The Lower East Side has high populations, extreme density, and contains vital infrastructure, yet it is one of the areas most at risk for flooding because it is built on infill. This initiative will develop and install an integrated flood protection system in the Lower East Side with permanent and temporary features that will be fully deployed only during pre-storm conditions. This system could be extended around the southern end of Manhattan. (2016)

Coastal Protection Initiative 22: Enhance protection to the area’s hospitals, especially Bellevue Hospital’s critical trauma facility. (2016)

Coastal Protection\Southern Manhattan Initiative 1: Design a flood protection system for the rest of Southern Manhattan and prepare a plan to implement it.

Coastal Protection\Southern Manhattan Initiative 2: Study the construction of a large levee on the eastern edge of Lower Manhattan which would provide protection against storm surge and sea level rise. On the new land, build a new neighborhood and use the sale of that land to finance other flood protection measures. This multi-purpose study allows for the reimaging of FDR Drive and would connect nicely with the extension of the Second Avenue Subway. (Launch study in 2013)

Buildings

Building Initiative 1: Improve building codes and zoning to reflect changes in floodplain data. (2013)

Building Initiative 2: Help rebuild housing damaged by Hurricane Sandy, including new resiliency measures

Building Initiative 3 + 6: Identify new ways to encourage design and construction methods resilient to flooding and increased winds.

Building Initiative 7 + 10: Launch a $1.2 billion program to provide incentives for resilient renovations of existing buildings. Buildings larger than 300,000 square feet will be required to adopt these investments by 2030. (2013)

Building Initiative 8: Establish Community Design Centers to help aid homeowners with resilient design.

Building Initiative 9: Repair public housing damaged by Sandy and include additional resiliency investments. 84 buildings and 10,000 units in Southern Manhattan will be repaired.

Building Initiative 11: Launch a $40 million competition to encourage development of cheaper, more efficient, and more resilient building systems.

Building Initiative 12: Clarify resiliency regulations for landmarked buildings and neighborhoods. In Southern Manhattan, there are over 170 landmarked buildings at risk. (2013)

Building Initiative 13: Expand DOB Facade Inspections to cover rooftop structures.

Insurance

Insurance Initiative 1, 4, 6: When Hurricane Sandy hit, less than 50 percent of residential buildings had flood insurance. These initiatives call on FEMA to make flood insurance more affordable.

Critical Infrastructure and Utilities

Critical Infrastructure\Utilities Initiative 5, 7, 8, 14: Examine which assets are most critical to the greatest number of people and make the necessary resiliency investments to energy transmission. This includes natural gas and steam providers. The hope is to speed up service restoration. (2013)

Critical Infrastructure\Utilities Initiative 12: To avoid the failure of one central component causing many people to lose power (called “Sympathetic Outages”), increase networks and redundancy, especially for hospitals.

Critical Infrastructure\Liquid Fuels 1, 4, 5, 8, 9: improve resiliency of gas stations, ensure there are back up plans to power New York City’s fleet of emergency vehicles, and create a collection of shared emergency supplies (ie generators) that can be immediately deployed.

Healthcare

Healthcare Initiatives 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9: Require retrofitting of current hospitals, nursing homes, adult care facilities, and mental health clinics on floodplains and ensure that new construction is resilient.

Healthcare Initiatives 10, 11: Improve the power and telecommunications resiliency of pharmacies to ensure that patients always can get access to their prescriptions.

Healthcare Initiative 12: Encourage electronic health record keeping to ensure that no patient’s health records get lost or damaged in a natural emergency.

Telecommunications

Telecommunications Initiative 1+2: Require Telecommunications providers to become resilient through the creation of the Planning and Resiliency Office that will have the power to enforce resiliency standards for telecommunications providers through New York City’s contract renewal process.

Transportation

Transportation Initiative 1: Reconstruct damaged streets, three linear miles of which are in Southern Manhattan

Transportation Initiative 3: Raise traffic signals and controllers at over 500 intersections throughout the city so that they are above flood heights.

Transportation Initiative 4: Protect New York Tunnels–maybe with permanent floodgates, raised entrances, or temporary inflatable tunnel closure plugs.

Transportation Initiative 6: Protect Staten Island Ferry and other terminals by raising them and improving their infrastructure.

Transportation Initiative 8: Encourage non-city agencies to implement resiliency strategies

Transportation Initiative 9: When the subway is out of service, there is not capacity in the rest of the transportation network to carry the increased volume of travelers–develop plans for transportation that can function in the event of subway outages.

Transportation Initiative 10: Plan for quickest recovery of transportation systems as possible

Transportation Initiative 16: Expand New York City’s High Capacity Bus Service (SBS)

Southern Manhattan Initiative 3: Even before Hurricane Sandy, Water Street was in need of significant streetscape improvements. This initiative will install new pedestrian-friendly sidewalk expansions and crosswalks, will improve signage, and will create permanent vibrant and attractive pedestrian spaces.

Parks

Parks Initiative 2: Increase resiliency of shoreline parks in order to protect developed regions beyond them (as well as the parks themselves).

Parks Initiative 11: Increase health of Urban Forest through increased forest management crews, expanding tree beds, and prioritizing tree inspections.

Water and Wastewater

Water and Wastewater Initiative 1, 2, 3: Increase resiliency of water and wastewater systems

Water and Wastewater Initiative 8: Through expansion of parks and Green Streets, reduce stormwater runoff in order to reduce combined sewer overflows.

Community Disaster Preparedness Initiative 1:

Community Disaster Preparedness Initiative 1: Taking an example community, analyze the strengths and weaknesses in order to better address a community’s issues.

Community Disaster Preparedness Initiative 2: Expand emergency response teams to better organize communities for natural disasters

Economic Recovery Initiative 1:

Economic Recovery Initiative 1: Launch $25 million sales tax waiver program to help businesses get back on their feet.

Economic Recovery Initiative 2: Launch a system for public grants for projects that spur economic activity and match public funding with private capital.

Economic Recovery Initiative 3 + 4: Support small businesses and nonprofits along certain corridors with discounts

Economic Recovery Initiative 6: Reassess commercial property values citywide to reflect post-Hurricane Sandy market values, effectively lowering taxes.

Southern Manhattan Initiative 4+5: Implement temporary and permanent public programing along Water Street to spur streetlife and eventually economic activity.

Southern Manhattan Initiative 6: Implement planned and ongoing investments in South Street Seaport area.

Southern Manhattan Initiative 7+8: Extend “Job Creation & Retention Program” and “HELM” program through at least 2017 in order to attract new businesses and jobs to Southern Manhattan.

Southern Manhattan Initiative 9: Continue with planned investments and construction by New York City and its partners (there’s a good list of developments–would be nice to show these on a map!).

1 Comment

Comments are closed.