As we continue to digest Mayor Bloomberg’s $20 billion-dollar, 438-page plan, “A Stronger, More Resilient New York,” we turn our eyes below the streets. We’ll be breaking down the plan to protect our 520 miles of shoreline and all that’s contained within section by section–from sea walls to healthcare to the power grid. In the meantime, we pause to look at the structures below. The physical underground of New York City is vast, and as it turns out, very much uncharted.

As we continue to digest Mayor Bloomberg’s $20 billion-dollar, 438-page plan, “A Stronger, More Resilient New York,” we turn our eyes below the streets. We’ll be breaking down the plan to protect our 520 miles of shoreline and all that’s contained within section by section–from sea walls to healthcare to the power grid. In the meantime, we pause to look at the structures below. The physical underground of New York City is vast, and as it turns out, very much uncharted.

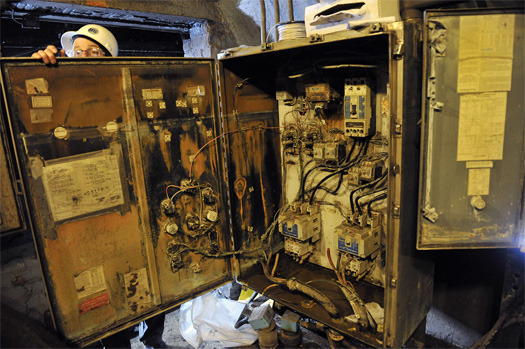

In a recent essay on the might of water, the needs, limits, and future of infrastructure, and the complexities of “rebuilding” whole systems or smaller features in the contentious and precarious literal and political landscapes of post-hurricane New York, Tom Vanderbilt reminds us that, “…the city does not have a single map showing the complex and twisting pathways of all its underground utilities.”

Between waterlines in Lower Manhattan and tours through the very permeable subway system with MTA engineers, Vanderbilt surveys various approaches to filling and creating gaps where needed between the past and future of New York’s built environment — in particular the systems beneath our paving stones.

Between waterlines in Lower Manhattan and tours through the very permeable subway system with MTA engineers, Vanderbilt surveys various approaches to filling and creating gaps where needed between the past and future of New York’s built environment — in particular the systems beneath our paving stones.

Restoring Zone A to the way it was prior to Sandy “raises questions — about the wisdom of rebuilding in places at high risk for flooding — that few politicians, federal or local, seem willing to broach.”

He continues:

At a conference at Hunter College a few weeks after Sandy, the outgoing Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Jane Lubchenco, offered an unusually frank assessment. “I think the language, ‘recovery,’ is itself problematic,” she said. “It implies what was — not what could be or should be.” At the same conference William Solecki, director of the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities [home of City Atlas], pointed out that in the past, urban disasters helped to inspire reform; the Great New York Fire of 1835, which caused devastating destruction, prompted calls for a more stable water supply: the result was the Croton Reservoir. Today, of course, the critical challenge is the region’s vulnerability to rising seas and dangerous storms. But what is the way forward? While there is immediate political capital to be gained in the reflexive narrative of recover-and-rebuild, the deeper and more urgent question concerns how New York City will need to be adapted and fortified, and not only in its built environments but also in our mental models.

For the full essay, turn to Design Observer.

Image: Design Observer