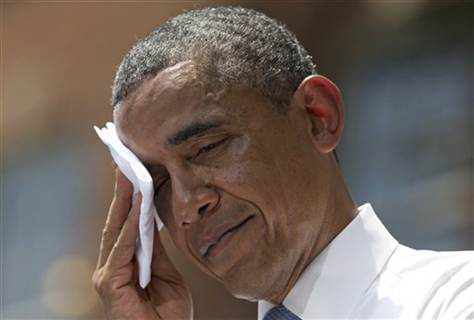

Long criticized for putting climate change on the back burner, the second-term Obama administration finally made a definitive stand for the planet last month. On June 25, President Obama delivered a speech at Georgetown University presenting the National Climate Action Plan (NCAP), a plan to fight back against global warming and overall climate change. The heat of the day (and President Obama mopping his brow) highlighted the importance and urgency of the speech’s content.

Two interesting follow-ups to the speech came from the Yale Forum on Climate Change and the Media, and the New York Times. The Yale Forum comments that the president wants us all to be climate change communicators. And Justin Gillis at the NYT notes that on college campuses, the president’s closing use of the word ‘divest’ resonated powerfully:

“It was a single word tucked into a presidential speech. It went by so fast that most Americans probably never heard it, much less took the time to wonder what it meant. But to certain young ears, the word had the shock value of a rifle shot.” (NYT)

_____

Here is a breakdown of the plan’s five main goals (adapted from the President’s speech and www.whitehouse.gov):

1. Reduce Carbon Pollution

- the Environmental Protection Agency will develop federal limits for carbon emissions through a transparent process

- those limits will be implemented in US power plants (new and existing)

2. Increase Use of Clean Energy

- invest in more efficient energy tactics

- accelerate the industrial transition to natural gas because it provides power, reduces carbon emissions, and creates jobs

3. Waste Less Energy

- develop new federal energy standards for appliances

- implement stricter standards in federal offices to reduce waste

- USDA will update programs to fund rural utility industry to finance sustainable habits

- expand the Better Buildings Challenge

4. Curb Emissions of Other Greenhouse Gases

- Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs)

- federal departments will develop an “interagency methane strategy”

- EPA to use Supreme Court-granted authority to promote efficient technology by encouraging private sector investments

5. International Leadership

- goal: by 2020, 20% of electricity used by the federal government will be from renewable sources

- share private sector knowledge with countries that switch to natural gas power

One of the most important components of the NCAP is the extension of EPA regulations to existing power plants. By including these plants, as well as new and future power plants, the Obama administration is addressing a significant contributor to the current carbon pollution problem. Another advantage of the plan is the identification of coal as “Public Enemy No. 1,” as noted in a Slate article, ‘The Best and Worst Parts of Obama’s Climate Plan‘ — which is a critique of the speech by Raymond Pierrehumbert, a top climate scientist. Carbon pollution is the driving force behind climate change, and burning coal is responsible for the majority of carbon dioxide emissions.

Taking action against coal is an important step in the name of the planet, but poses political repercussions for both the Obama administration and Democrats in general–and caused a predictable outcry from coal states. Most U.S. coal plants and 75 percent of the nation’s wind energy sources are located in Republican districts. The coal industry is a major employer in those regions; the new national plan seeks to transfer these jobs to private sector and natural gas industry employers. According to a recent New York Times article, the GOP sees an edge in securing its supporters and gaining more in energy-rich states and those with an active coal industry. Democrats in those states have had to distance themselves from the attack on coal that is championed by their counterparts in other states and Washington D.C. These office-holders are put in a tough predicament by the implementation of the NCAP, especially in light of the trend of energy-rich states transitioning to red states.

Many climate experts have questioned the plan’s potential for long-term improvement of climate health. To some, the plan looks more like an accumulation of Band-Aid type measures to settle issues only for the time being; subsequently, a major criticism of the plan is that it neither changes nor challenges the mentality of the atmosphere as Earth’s wasteland.

Another of the plan’s shortcomings is its failure to address U.S. coal exports. As domestic demand decreases, international demand increases. For example, the rate of new coal power plants opening in China and India is steadily increasing to almost one per week. If coal exports are continued at their current rate, any benefits reaped by the President’s plan may be negated. It may even cancel out the effects of the U.S. switching more readily to natural gas. Charles Krauthammer of the Washington Post worries that Obama’s plan “will simply shut down the U.S. coal industry and ship it abroad.”

There is also apprehension of the United States’ ability to lead the world by example, or that the rest of the world will readily follow. Because we all live on the same planet and all contribute to Earth’s condition, if the majority of the world does not make efforts to combat climate change, why should Americans suffer through hikes in electricity costs and potential job loss?

In addition, President Obama’s plan puts emphasis on Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs) such as methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and tropospheric ozone. SLCPs and other climate forcers are to blame for a small amount of trapped greenhouse gases, but have a relatively short lifespan compared to carbon, which is the main contributor to global warming and remains in the atmosphere for millennia. This information raises the question that the U.S. must face: Should we dedicate expertise, time, and money fighting short-lived climate pollutants now, as the NCAP calls for, or wait until measures to reduce carbon pollution are underway? The Obama administration has made a decision in answering that question, but only time will tell if it was the right one.

Perhaps even more important than policy specifics, the speech carries with it a plea for help from the president. Justin Gillis’ analysis in the NYT:

[Obama] knows that if he is to get serious climate policies on the books before his term ends in 2017, he needs a mass political movement pushing for stronger action. No broad movement has materialized in the United States; 350.org and its student activists are the closest thing so far, which may be why Mr. Obama gazes fondly in their direction.

“I’m going to need all of you to educate your classmates, your colleagues, your parents, your friends,” he said plaintively at Georgetown. “What we need in this fight are citizens who will stand up, and speak up, and compel us to do what this moment demands.”