This week President Obama revealed a new plan to address climate change by regulating emissions from power plants, including those powered by coal, reducing CO2 from the plants by 30% from 2005 levels. Great strides towards a more stable climate come from cutting the major sources of fossil fuel emissions through policy change and technological developments. To see such powerful action is to gain hope.

But when one takes time to study the issue, it becomes apparent that these latest political efforts will likely not be enough to curb U.S. emissions at a rate that can meet the global target for a safe climate. Even a carbon tax may no longer be fast enough, or fair enough, at levels that would be politically viable.

Global warming is an issue that calls for systematic overhaul of infrastructure and individual action. In this case, individual action is the conscious effort to change one’s behavior and lifestyle to reduce one’s carbon footprint. We are responsible for our consumption, for everything that we own, purchase, and use. Every time we take a flight, or drive a car, or buy a new gadget, we are pushing the climate system, because our energy supply to travel or to manufacture things is still mostly based on fossil fuels.

[pullquote align=”right”]To think of personal reduction of demand as essential, rather than optional, creates an entirely different mindset.[/pullquote]

Therefore, to take action on climate change also means to restrain our own demand for energy, even while building clean energy sources as quickly as possible. The call for personal responsibility has been used before, but as the outlines of the challenge become more clear, some researchers see a new understanding of energy and behavior as key parts of an overall solution.

To that end, the United Kingdom’s Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) created online simulators that model the UK’s fossil fuel reduction goals. The simplified ‘my 2050’ “pathways calculator” breaks down the possible action scenarios the government can take. The calculator gives online users the opportunity to try to balance the supply and demand energy equation while reaching an 80 percent reduction of fossil fuel use by 2050, a target, which on a global scale, gives the world a chance to peak at or below +2°C warming. (We’re at about +1°C now, and 2°C is recognized as the highest safe level by the IPCC, the world scientific body that reports on climate.)

On the supply side, along with the options of wind, solar, and hydropower, the ‘my 2050’ simulator includes nuclear power, carbon storage, biomass, geothermal, and imported electricity. The demand side includes areas in which to focus possible reform: home insulation (and lower heating), electricity, cooking, transportation (mass transit, electric cars), etc. The user determines the levels of each energy source, and also controls the levels of demand, including which categories to reduce entirely, partially, or not at all.

As you adjust the supply levels, you will realize that no matter how much you reduce your supply of fossil fuels in favor of renewable sources of of energy, it is impossible to reach an 80-percent reduction in fossil fuel use and still meet our current energy demands. Changing how or from where we get our energy is not enough to balance the equation. New infrastructure and technological solutions must be accompanied by behavioral change to reach the 80-percent target in emission cuts.

In other words, the British government is relying on the effect of sweeping behavior change among British citizens in order to meet its own emissions targets. (How to facilitate that social change is the subject of a recent report from the Royal Society of the Arts.)

Though the simulator is a UK-based model, its lessons apply to the rest of the world, particularly to the United States. The United States has far more land area than the UK, and thus more opportunity to develop renewable energy. However, like our counterparts in the UK, American citizens must also make behavioral changes if we are to reduce our fossil fuel use enough to remain within 450 ppm of carbon in the atmosphere by the end of this century, which has been the target of world negotiations. (450 ppm is expected to be equivalent to a 2°C maximum increase in temperature.)

David MacKay, University of Cambridge physicist and Chief Scientific Advisor of the DECC breaks down the numbers a bit in a piece for The New York Times which considers the average European daily energy use of 120 kwh. To sustain such an appetite entirely on renewable energy would require setting aside 300 square meters of desert for remote solar energy production–or 1980 square meters of land for wind energy–for each person.

MacKay points out that to generate a modern European lifestyle for everyone on Earth, and to do it from renewable resources, would bury much of the planet’s remaining natural land in energy facilities. (More detail on MacKay’s research is in his online book on energy.)

That’s what happens if we don’t scale down demand. Alternatively, a nation’s population can import energy from foreign countries, or—get this—reduce their personal consumption. He has no doubt that with “lifestyle changes and determined switches to more efficient technologies for transport and heating,” it would be possible to keep a comfortable life and cut in half a person’s energy consumption. And this is much easier than building power stations and coping with an increasingly chaotic climate system.

It’s obvious that our own action—and the collective action of everyone—is not only desired, but necessary to curb the effects of climate change. To think of personal reduction of demand as essential, rather than optional, creates a mindset which is entirely different than that shared by most in our world today.

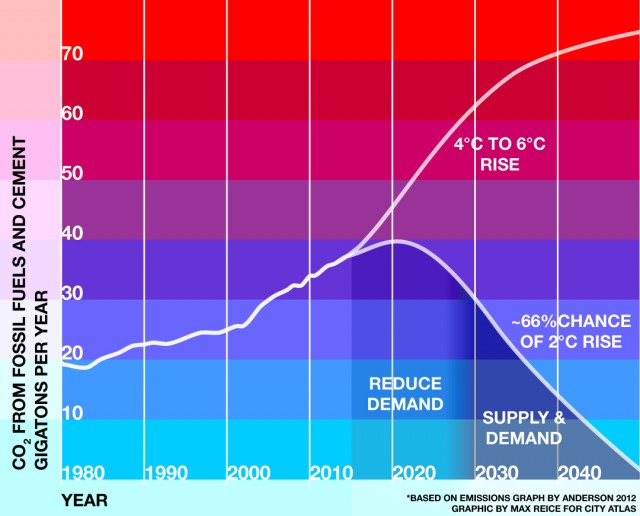

Kevin Anderson, Deputy Director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research, a research consortium of British universities, makes the case that a reduction in personal footprints is also the crucial first step in combating climate change. In a presentation for the Tyndall Centre, Anderson graphed the projected increase in carbon emissions due to economic growth, showing that by 2050, we will have secured our path to a 4-6 degrees Celsius rise in global temperature, a rise widely accepted as a catastrophic increase for the U.S. and the world. There is, however, an alternative future. If we constrain our emissions, and began to turn the clock backward around 2025, a rapid downward trajectory towards 2050 will allow us to remain within the 2-3 degree Celsius range.

You can check Anderson’s predictions on an MIT simulator that allows you to set a rate at which to decarbonize our global economy in order to prevent catastrophic climate change later in the century. To play the MIT simulator, choose ‘Experiment 2’ and select ’20 year delay.’ Remember that you cannot fairly begin to decarbonize before 2014, as we can only start in the present–or near future.

Anderson’s goal of peaking emissions at 2025, however, is too soon for the development of enough renewable energy capacity to make an impact. For that, we need to change our behavior while the technology catches up.

“What we know,” Anderson explained in an interview with Transition Culture, “is that in the short term, because we need to start this now, we cannot deliver reduction by switching to a low carbon energy supply, we simply cannot get the supply in place quickly enough. Therefore, in the short to medium term the only major change that we can make is in consuming less.”

Anderson’s stark numbers expose the most challenging aspect of climate policy – is economic growth possible while rapidly decarbonizing our societies? Anderson believes that we cannot have continued economic growth if we are to avoid a 4-6 degrees temperature rise, which is a deal-breaker for politicians, business leaders and most economists.

Anderson and MacKay’s perspectives align in the belief that the reduction of one’s own personal demand for fossil fuels is not only necessary, but must also come first, before the big strides, such as energy storage, widespread renewable generation, and political change are fully realized. Whether that curtails growth – which is, in part, a question of how growth is measured – is something we will look at in future City Atlas posts.

If we choose a diet with less beef, fly less, drive less, insulate our buildings to reduce our electricity needs for heating and cooling, and more, our collective effort can reduce demand for energy. Furthermore, the change in demand will shift the market towards less high-carbon practices, incentivize elected officials to push for greater political initiative, spur investment in R&D, and snowball momentum for a majority of the population to recognize and take action against climate change. Anderson explains this as the ‘bottom-up approach.’

According to MacKay and Anderson, we need to address our own demand for energy before we can rely on a fix from the political system or new technology. Our culture will not make these profound and necessary changes without some of us leading the way, establishing new norms, and changing first.

_____

Addenda: a forthcoming article in Harpers includes the assertion from John Podesta, White House aide, that the recent EPA ruling on power plants does not represent a strong enough measure to achieve the 2°C target. ““Maybe it gets you on a trajectory to three degrees,” [Podesta said] “but it doesn’t get you to two degrees.”

Economic columnist Eduardo Porter on the EPA initiative in the New York Times.

A review of climate trends and impacts for the United States is available in the National Climate Assessment.