“Keep it simple. Keep it slow. Keep it quiet. Keep it wild,” reads the sign in big block letters. These four rules make up the design mantra of the High Line Park, which opened in 2009 in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District and has rapidly become one of the city’s most popular attractions.

Just a few flights of stairs beneath our feet are speeding yellow cabs and loud restaurants and steaming sidewalks. But up among the greenery of the High Line, children splash in fountains, couples lie on the grass, and New Yorkers in search of simple, slow, quiet and wild duck under low hanging leaves.

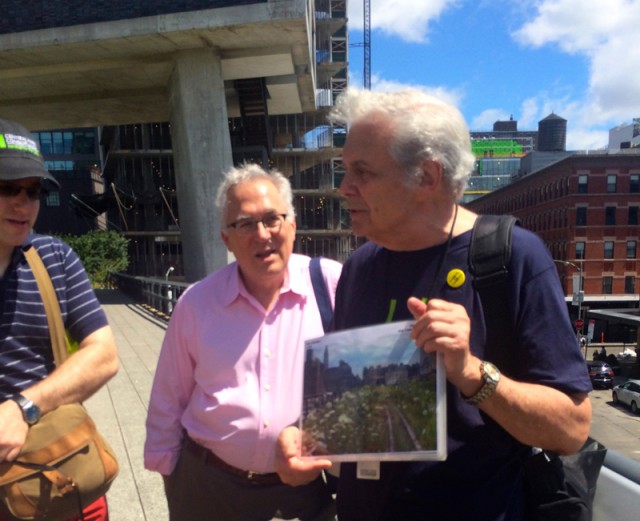

I’ve been here before to wander, but this time I’m on an official tour led by Ken Naarden, a volunteer with Friends of the High Line, a non-profit organization dedicated to maintaining the park and engaging the community. The event is sponsored by Yale Blue Green, a group of alumni, students and faculty engaged in sustainability topics and issues, and the local Yale alumni association.

With me are several Yale alums with diverse perspectives on the High Line as a New York landmark: long-time residents of the city, first-time visitors to the High Line, environmental enthusiasts. Bernadette Sebzda works in real estate, and is focused on green building practices. To her, places like High Line are vital features of any city.

“Look down at the street,” Sebzda says, gesturing out beyond the lush, tree-lined wall of the High Line to the street below. Without trees to provide shade, heat is absorbed right into the concrete, which exacerbates the “urban heat island” effect. “It’s a frying pan,” she explains. Up on the High Line she gets a rare chance to breathe oxygen.

Maxwell Kushner-Lenhoff, who organized the event, agrees. “Whoever you are, you’re going to benefit from green space and fresh air.”

But it wasn’t always like this, Ken explains dramatically. We stop to look out over 10th Ave., or, as Manhattan pedestrians once called it, “Death Avenue.”

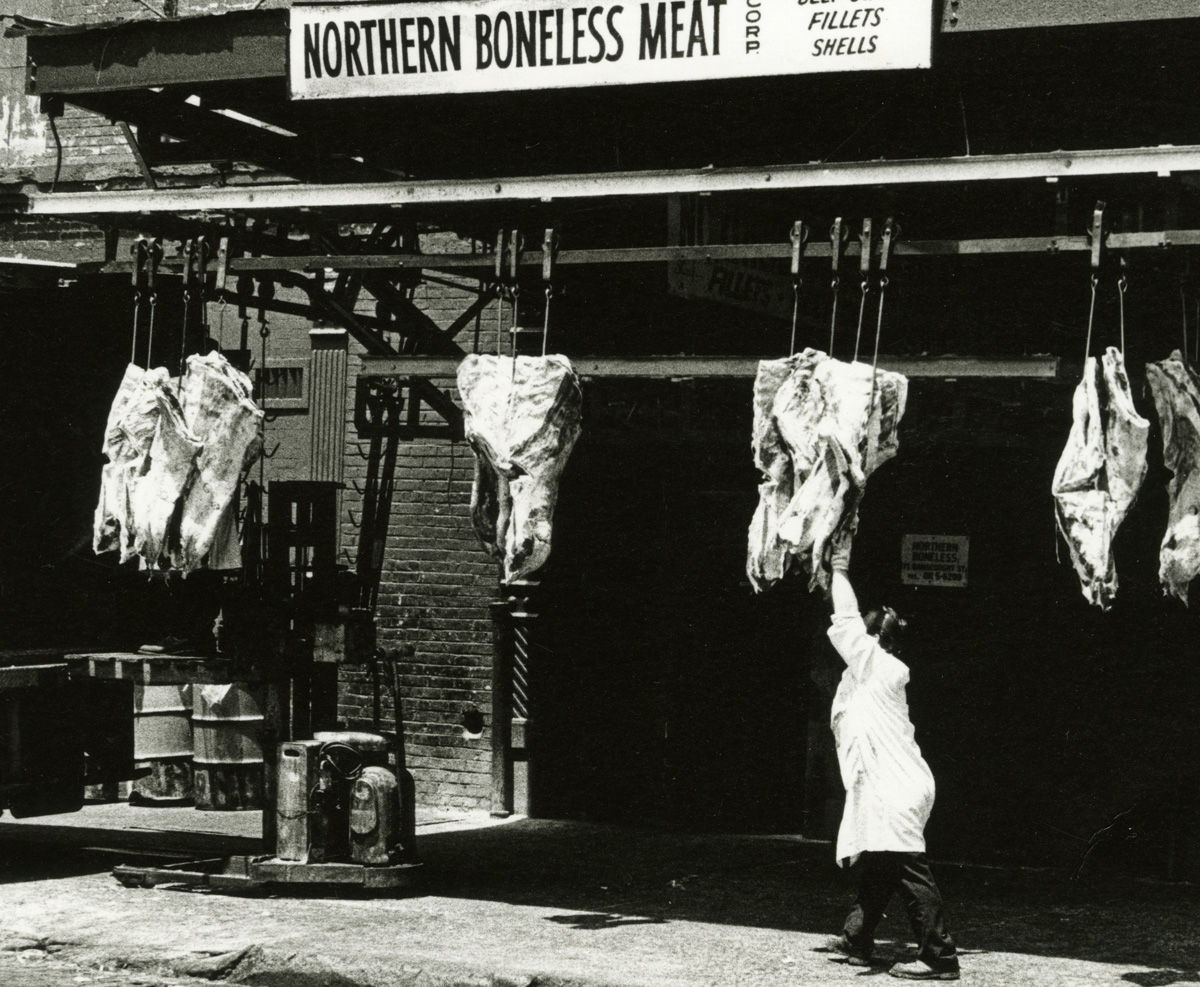

The Meatpacking District, where the High Line starts and where we stand sweating today, used to be home to hundreds of meat packing factories — cows hung from meat hooks in the streets, and turkey heads lined the avenues. In the 1920s, trains, cars, and horses would run undirected by traffic lights, and people would be hit regularly by oncoming vehicles or animals.

By the 1930s, Fiorello La Guardia, the mayor at the time, realized something had to change. He collaborated with city planner Robert Moses to find the solution: bringing the trains up off the ground. Aided by efforts from the West Side Improvement Project, the High Line opened to trains in 1934. Thousands of pounds of meat continued to be pulled over these tracks until 1980, when the interstate trucking industry made freight trains all but obsolete.

Years passed. Wild flowers started to grow over train tracks; weeds crept up the side of loading docks; the passage of time began transforming the High Line into an abandoned jungle. Some residents called for its demolition. In 1999, residents Joshua Davis and Robert Hammond started advocating for its preservation instead, forming the original “Friends of the High Line.” They solicited suggestions as to what the abandoned railroad should become: a swimming pool that spanned 20 blocks, maybe, or a roller coaster, or a shopping center. In 2004, the city came to a consensus: to follow the course nature had already set, and turn the High Line into a public park.

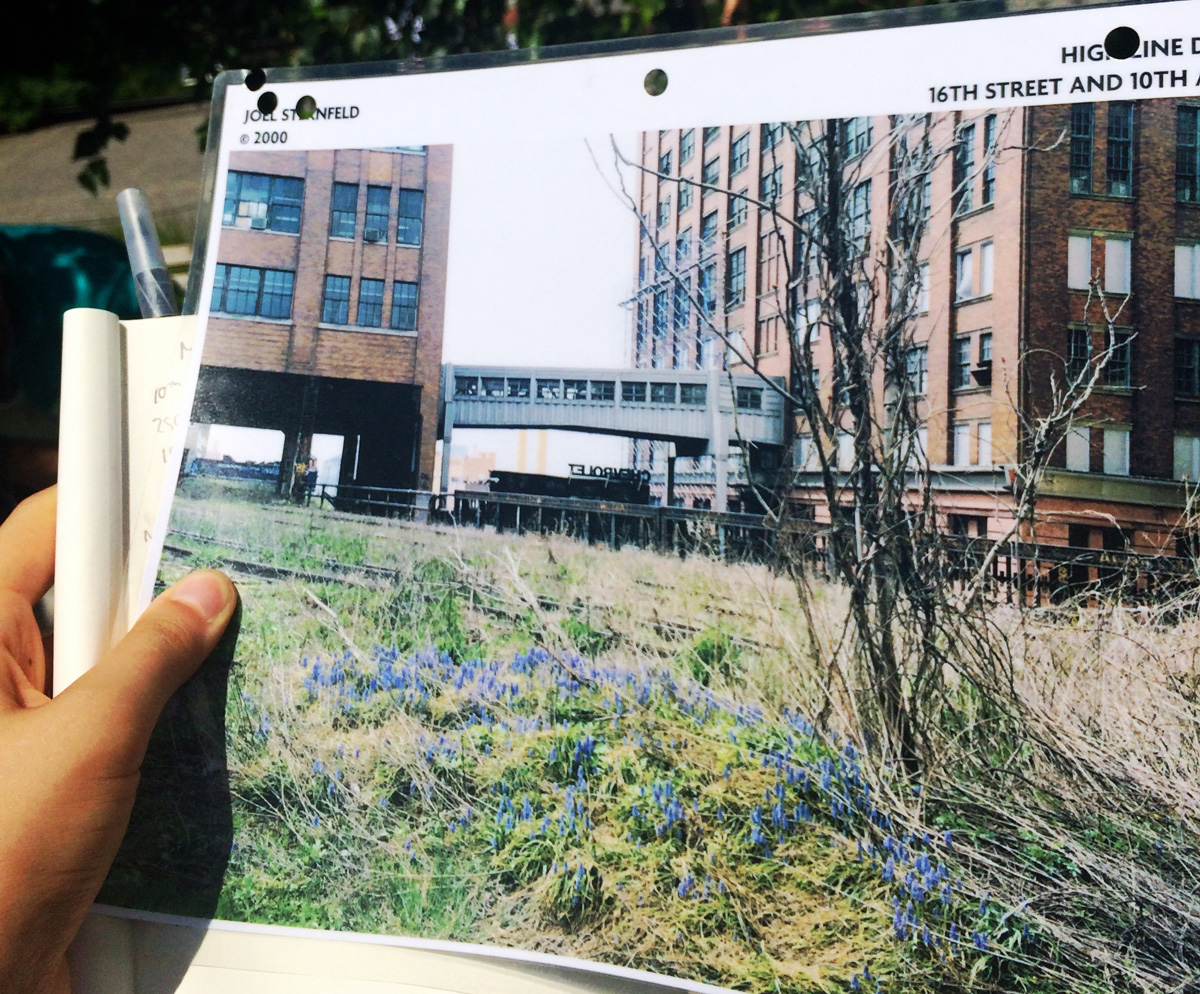

As our group makes its way down the path more than a decade later, Ken shows us a photograph of the High Line then, purple flowers flanking both sides of rusted metal tracks. I look down at my feet to see the High Line now: set into the concrete are those same tracks; planted beside are those same flowers.

To our right crouch three gardeners, elbows deep in soil. Along with 11 full-time professionals, hundreds of volunteers like these help plant flowers and maintain the High Line’s landscape, designed by Netherlands-based horticulturalist Piet Oudolf. He had the unique task of choosing plants that could survive during all four seasons, under varying degrees of shade, sun, and weather. This complex combination of microclimates reflect the original conditions of the High Line, and the plants Oudolf chose mirror those naturally occurring plant communities.

A young boy runs through the middle of our tour, splashing through puddles made by a fountain spraying the path. The water disappears quickly between the concrete tiles and down slanted slats into the ground — this is part of the High Line’s sophisticated drip irrigation system, which is designed to direct rainwater into the planting beds.

Because of the High Line’s commitment to sustainability, these plants don’t even need much water at all. Most of them are locally sourced from within a 100-mile radius, produced by local growers, and are native species to the Northeast. Local plants that thrive already in this climate need less watering to maintain and have a greater chance of success, conserving natural resources.

The beds, soil, plants and rails from the original High Line were lifted when construction began in 2004, Ken tells us. Each rail was marked with a GPS coordinate and put back exactly in its original position, now embedded within Oudolf’s new, adapted ecosystem.

The art on display, too, pays homage to the surrounding environment, both urban and natural. Some of us stop for ice cream under a bridge (it’s hot!), and take the opportunity to stare at an enormous stain-glass piece that stretches from floor to ceiling, called “The River That Flows Both Ways.” The artist Spencer Finch spent a day floating in a boat down the Hudson River, and took a photograph of the river’s surface once every minute for almost 12 hours. Blues and yellows and greens undulate left to right like the tides, while the real Hudson River is blocked by the brick wall the piece is hung on.

We continue the walk, passing the home of the first Oreo cookie, the headquarters of the DEA, the Standard Hotel, Chelsea Market, and the homes of some of the most wealthy New York residents. Only four out of 250 of the original meatpacking factories exist today.

In a city that’s constantly changing, the High Line exists to preserve New York’s history, both physically and in the minds of its visitors. But in doing so, it is itself spurring some of the most rapid change. Practically all that remains of the Meatpacking District of the 90s are its railroad tracks, and not everyone is happy about that. By 2012, three years after the park opened, preservationist Jeremiah Moss was describing the High Line as “a tourist-clogged catwalk and a catalyst for some of the most rapid gentrification in the city’s history,” and “…good news for the elite economy but not for many who have lived and worked in the area for decades.”

Perhaps the transformation of the neighborhood was inevitable. Boutiques and restaurants had spread through the neighborhood before the park was complete, and Manhattan as a whole has experienced some of its most rapid evolution, part of a surrealistic, globalized high-end real estate market, over the past 10 years. But the correlation between the High Line and luxury residential development in the surrounding blocks is self-evident; it’s an anchor for a swanky neighborhood.

According to a UC San Diego study, from the moment the High Line was built, all property values in ⅓ of a mile radius increased by 10%. And from 2003 to 2011, property values surrounding the High Line grew 103%. All along the High Line’s path, large hotels and high rises replace factories, and up-scale restaurants and expensive shops replace the corner stores, bars, and meat hooks that used to characterize these blocks. The New York City Economic Development Corporation (the development agency for the City) reported a sharper rise in real estate value around the High Line than around Central Park — though both are surpassed by the changes around Prospect Park in Brooklyn.

Bearing in mind the critiques, the High Line has been both a huge real estate success and an everyday civic success. (You can’t stop tourists from going there if they like it.) It’s become a model for recycling old infrastructure in cities around the world, and an inspiration for proposals like the QueensWay. And for many New Yorkers who spend their days inside or walking down frying-pan streets, the High Line works as an urban oasis. “Green spaces like this are an escape,” Sebzda says. “They show what a city can be.”

Photography by Sarah Holder: