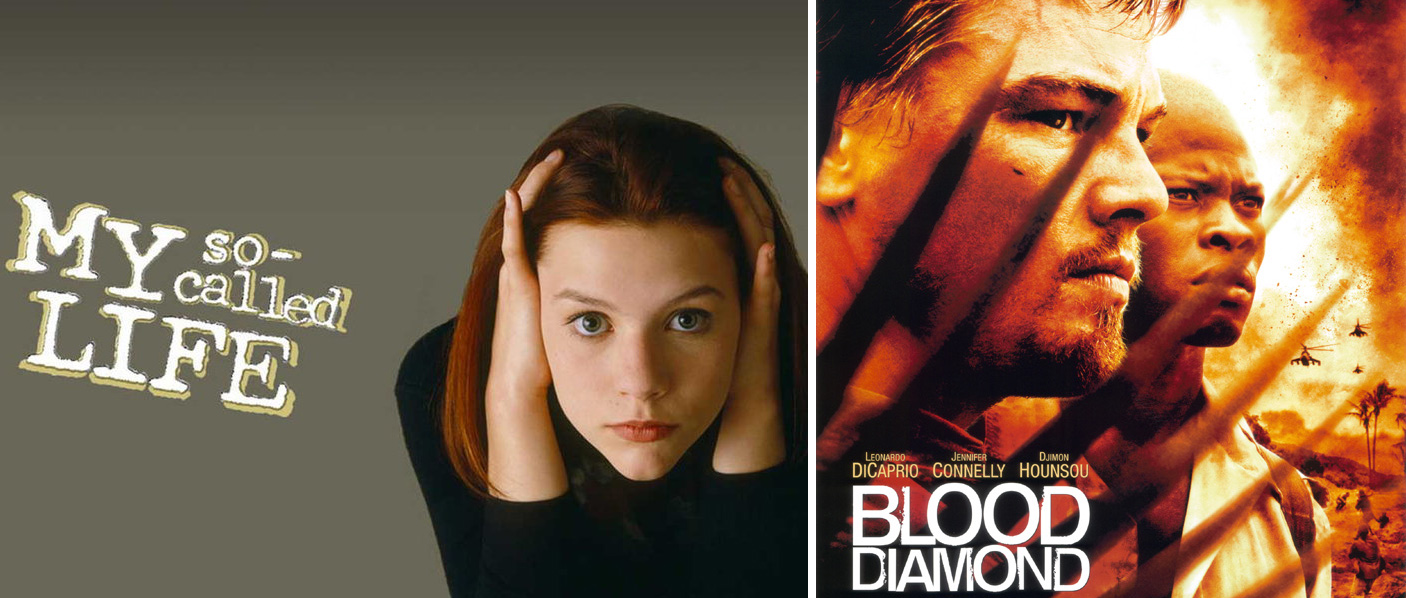

In this post, we’re broadening our scope of interviews to include influential figures outside of New York. Marshall Herskovitz is a Hollywood producer, director and screenwriter who has also served as president of the Producers Guild of America (2006 – 2010). His credits include films such as “Traffic,” “The Last Samurai,” and “Blood Diamond,” and with his creative partner, Ed Zwick, he created the groundbreaking television series “thirtysomething,” “My So-Called Life,” and “Once And Again.” He and Zwick recently made news for signing a first-look deal for television with Lionsgate Television.

Alongside his career in the film industry, Herskovitz has devoted years to thinking about our society’s climate change problem. He shared his thoughts on communications with Abigail Carney:

What got you thinking about climate change?

I first got into this more than fifteen years ago, just by reading the science and getting really terrified. There was a big dividing line before and after “An Inconvenient Truth.” Before “Inconvenient Truth” the issue really was that people were not aware of climate change. After “Inconvenient Truth,” it became more complicated because people were aware of it, but it became much more politicized.

So, before “Inconvenient Truth,” I was trying myself to put together a large communications campaign to get people aware of it, and I ended up through this weird, flukey thing, testifying in front of a committee in Congress. And basically what I was saying then is what I say now, which is that we are not even remotely on the right scale of what we need to be doing, and that we are all still in denial…and that, except for a small group of very vocal people, even among people who are really on board in terms of moving to combat climate change we aren’t really thinking about what we have to do. The only analogy for what we have to do is a World War Two-style mobilization.

What’s keeping us from doing what we need to do?

The whole denier sort of infrastructure has managed to convince people that in order to fight climate change, you have to harm the economy. I think that single piece, that sense that we have to destroy our way of life in order to save the Earth has been the most destructive thing, and is a complete lie, the total opposite of the truth.

And, just like in World War Two – World War Two transformed the economy of the United States. The Depression did not really end until 1942. We were still in the tail end of the Depression, and it had already gone on for ten or twelve years. It took World War Two to get us out of it.

The same kind of economic explosion will happen when we start to move at that scale on energy. So, for me, the issue is, how do you communicate that? That’s been my issue for fifteen years, it’s a communications problem. And, you know, I think I know a way, but it’s very expensive and I’ve never been able to convince anybody to put up enough money to do it.

If you watch CNN, every third commercial is either from natural gas or the Petroleum Institute, or the other petroleum companies extolling the virtues of fossil fuel energy. They are all in the aggregate spending probably a billion dollars a year on advertising for fossil fuels. I always say to people, “They are not stupid. They’re not throwing that money away, they are doing that for a reason.” It’s been astonishingly difficult to get anyone on the other side to think of spending that kind of money on communications. Even though it’s obvious that that’s what needs to be done. So that’s always been my frame of reference, that this is a communications problem. It’s not a technological problem, it’s not an economic problem, it’s just a communications problem.

Say we solve the communications problem, do we have the technology to limit our carbon emissions? Do we have the technology we need to communicate?

We have the technology. There are a few areas where we don’t have technology yet, but we’re very close. The biggest area where we don’t technology yet is in in storage of electricity, but we are very close, and we in fact have things we could use in the interim, including Tesla’s new batteries, and molten salt [used to store heat in solar thermal power plants]. There are ways to store electrical energy, but the point is we are on the brink of this twenty-year process where we are going to completely revolutionize electrical energy in the world, and what’s standing in the way right now are the public utilities, public utilities commissions, who will lose their economic model if we do that.

So what are we communicating? What’s the first step?

If we were to convince 20 million businesses and homes to put in solar, that would begin to destroy the infrastructure of these utilities. Okay, so then as a nation we’d have to face the fact that utilities have to have a new economic model. To me, that’s the first thing we need to deal with, and it’s already happening. In LA right now, PG&E is trying to pass a rule that charges people with solar an extra amount every month that basically would wipe out all their savings from solar. And they’re saying, that’s because people with solar aren’t paying their fair share of keeping up the infrastructure of the electrical grid and all that, but that’s actually not true, because I think everyone would be happy to pay their fair share of keeping up the electrical grid. What costs the money is the creation of the electricity, and that’s where they are not telling the truth. It’s the biggest roadblock right now.

Do you think that the narratives to create that action are there? Do we already have the stories we would tell if we had billions of dollars to spend on advertising?

Yes, we have the professionals who could do it. We have the professionals who could create the stories. Absolutely. Totally. In other words, the wrong people have been doing this. The wrong people have been handling communications, that’s the problem. The problem is that the heavy lifting of teaching people about climate change, has been with all of the NGOS….NRDC—

Sierra Club…

All of them. Okay, they are all amazing organizations, but their frame of reference is political activism and policy. Their frame of reference is not mass communications, and that’s been the problem.

I live in mass communications. I live or die by whether millions of people come and pay to see my product, and advertisers, the big advertising agencies, live or die by whether they get millions of people to respond, and that’s where the communications have to come from, and that costs a lot of money! Because you’re talking about television buys, and you’re talking about the kinds of marketing efforts that I’ve seen happen scores of times in my business. Where, for instance, we make a movie, nobody’s ever heard of that movie, you know? We then take 30, 40 million dollars and four weeks later, 96% of Americans know all about it. This is a very well established discipline, advertising and marketing, it just hasn’t been applied to this. So, that’s, to me, what still needs to be done.

Even though we are seeing, for sure, that the tide is turning in America, there’s no question about it. There’s no question that a majority of Americans believe that one, climate change is real, two, it’s caused by humans, and three, that we need to do something about it.

I sort of keep track of these numbers, and basically, about 20-25% of Americans think it’s an emergency. And then there’s another 40% who think that we have to do something, but they don’t know what to do and they feel overwhelmed and so they don’t really deal with it in their lives. And then, on the other side, there’s another 35% who either don’t believe, don’t care, and a smaller percentage of them are actively opposed. But about 65% of Americans think we gotta do something, it’s just that we need a much bigger percentage of those people to become active. We have to make it possible for them to do something about it. Right now, they go, “It doesn’t matter what I do, you know? Even if America acts, what’s China gonna do? What’s India gonna do?” It’s changing that perception, and there are ways to do that.

The biggest thing we are not exploiting is self-interest. Right now, there’s something like 120 million buildings in America. And every one of those buildings could be cheaper if it either was more energy efficient, or created its own energy. That’s a huge constituency. That’s a huge market. And most business owners don’t have any concept that they could be saving money, most homeowners think it’s expensive still. People are not aware of what’s available to them right now. It would be very simple, in a marketing campaign, just to show people how they can be saving money right now.

The interesting thing is that when you own a business, you understand that saving money is the same thing as making money. It’s funny because in our homes we don’t think of it that way. As private citizens, we think saving money is nice, but making money is better. In a business, you understand that it’s all the same thing, You have a balance sheet and you know if you can make your expenses lower, that means you made more money! So, the point is, there are ways to start saving money today, by moving to renewable energy and that’s an easy message to get across and it’s not happening.

Where would you be pushing people to act with this marketing campaign? Would it be a move into political action? Once people have made their homes and businesses more efficient, what is the next step?

What you are asking is a really good question. We now understand that the Tea Party movement was organized and funded by the Koch Brothers and others, and was not a grassroots movement, but was in fact a highly organized and focused movement. And what they did was study successful social movements in the past, including the civil rights movement, and they discovered that these movements work by being incredibly disciplined, and by staying on message. The civil rights movement was very organized, and there was a very clear command structure. They were able to use churches because the black community revolved around local churches, so that was a natural sort of organizing spot. There was nothing random about it.

They knew exactly what they were doing, they knew exactly how they were organizing people, and the Tea Party movement borrowed a lot of those techniques in terms of creating these chapters around the country, but it took a lot money, it took three, four hundred million dollars to do that. So again, yes, we need grassroots organizing about climate change, but that can’t happen without that kind of central organization. People don’t want to admit that.

You know, it’s so interesting in America that the left is always disorganized and the right is always over-organized. It’s like a personality difference. Here you have this amazing thing, Occupy Wall Street, which was this remarkable sort of expression, and not only were they disorganized, but they in fact fetishized disorganization. It was exceedingly important to them that they didn’t become organized, and so it frittered away. Because you can’t ultimately get anywhere unless you are organized. There has to be some combination. So yes, I think we need people in the streets, peacefully. We need people in the streets, in the hundreds of thousands, around the country, day after day, getting this message across that this is an emergency. At the same time we need this economic message, and we need people to move.

My feeling is that the minute you do anything, the minute you spend money making your house more efficient, or putting solar on your roof, you are then a constituent. You are a part of the movement then and your consciousness has been changed by doing that. I remember the first time I bought a hybrid car. It blew my mind. I was thinking, “My God, all these cars around me are just wasting energy when they are at a stoplight.” I never thought about that before. When you see it a different way, that then extends itself to every aspect of your life.

So, a lot of this is political, we’re gonna need political change, we’re gonna need changes in policy, in rules, in regulations, all that sort of thing. You need a constituency for that you, you need people who will vote for it. It’s a chicken and egg problem. This is a problem that has six chickens and seven eggs, it’s like, ‘this has to happen before that, which has to happen before that,’ and it’s very complex and difficult. How do you get people on board when there’s not many [things] they can do tomorrow, you know? And for me, one of the answers is: get them to do anything. Get them to spend their money on something that will make a change in their own life. If it’s buying a car, that’s great. If it’s changing their lightbulbs, that’s great. If it’s putting in solar, that’s great.

We have to make it easier for people to have community solar, that’s a huge thing that we are going to have in this country, where, every church, every school every factory, every huge roof, has capacity for solar way beyond the needs of that organization. And the neighbors, they can invest in that, and get a check every month. That’s easy to do, but we don’t have rules that allow it right now. There are a hundred things like that that will change people’s perceptions of their communities, or their own power to make change in this area, so, there isn’t a simple answer, there are a lot of answers, and they are all around engagement.

When you use the example of the Tea Party movement, and say how some central structure and funding was so crucial to that, do you have any idea of where that will come from?

No, because no one’s doing it. Okay, we have Tom Steyer. Tom Steyer, whom I met once, I had a very interesting meeting with him, he’s clearly a very bright man.

I argued with him about natural gas. He was saying, we need natural gas as a bridge to true sustainability. And I was saying, I’m not going to argue against that, but my point is that, from the standpoint of communications, natural gas is a bad idea, and here’s why: The revolution in energy is going to come when millions of people spend their money to change their relationship with energy. It’s millions of transactions, that’s what’s going to create millions of jobs. In other words, when I hire a guy to come to my house and retrofit my house, or put solar in, those transactions, if fifteen million people do that, that’s a revolution, okay? And with natural gas you don’t have to do any of that, it’s the same big companies. So, it’s a matter of perception. In other words, you are not engaging the public when you are using natural gas.

What do you think about nuclear?

I think nuclear is a disaster. Here’s what I say to nuclear: you’re looking for a house to buy. Someone shows you a house, it’s the most beautiful house you have ever seen. Everything in it is gorgeous. You are looking through the house and you go down to the basement, and you discover that every toilet in the house flushes into the basement and all the shit just stays in the basement, and they say, “We don’t know how to fix that. It’s just gonna be like that, forever.” That’s nuclear power.

It’s been 70 years and we don’t have a solution to nuclear waste, aside from all the other problems with it. And the main issue is we don’t need it and a lot of people think we do, but we don’t. We have technological solutions now that are safer and cheaper than nuclear power. We just don’t have the will to implement them.

I think Steyer is making headway, and I think he’s really smart, so he’ll do what he does, but I’d like to see somebody like Steyer, who has the money, take the people that McKibben has organized. But McKibben – whom I’ve spoken to many times on the phone – he’s an interesting guy and he does not want to be the guru, and he does not want to be the power player and he doesn’t want to become the establishment in some way. And that limits the power of 350.org. Yet 350.org has the most people and has the most firepower, and in some ways, because of its own ethics, won’t use them, do you know what I mean? And I think we need an organization five times bigger than 350.org and four times more willing to use its power. That’s what we need. And that can be done, it just takes a lot of money. That would be very influential.

Could some related influence come from Hollywood?

My business is a disaster in this area. There’s no interest at all. I tried to sell a pilot that dealt with climate change this year. Not one network would go near it.

Really?

Wouldn’t go near it.

And was climate change very central to it?

It took place in 2085. It existed in a world that had been utterly transformed by climate change; climate change was everywhere. It was called “Storm World.” In the opening scene, you have a guy in his kitchen in New York City, and he’s looking out the window and you are seeing the beautiful trees and a nice vista; he does a little gesture and all of a sudden the window changes to what’s actually outside – a Category Four hurricane. A giant branch hits the window and bounces off because everything is reinforced.

Basically, they just live in storms all the time. And it just goes on from there. In the show, by 2085, 25 million Americans had to be removed from where they lived because where they lived had been inundated, and so they set up what they called “The Territories” in the West. Most of the Dakotas and Utah had been turned into, essentially, refugee camps for 25 million people to live because there was no other place for them. And these were Americans. This displacement had completely messed up the economy and the politics of America.

So the show was essentially trying to say: this is what is going to happen if we don’t change, that’s the world we are going to live in. The story itself was somewhat of a melodrama. It was using climate change as the background.

And why do you think none of the networks would go near it?

Because they are not in the business of making people mad. In other words, they are trying to maximize their audience, and this is still very polarizing in the country. I think they feel that for a lot of people, it’s a turn off.

Among the people you work with, is there a general awareness and a sense of urgency? Is it just that they don’t want to offend the parts of the country that are still anti climate action? Or, is it an issue that is not on the minds of most people who are working in the industry?

It’s very much on people’s minds. I just think they feel powerless, they don’t know what to do about it. I feel like I’ve been more active than any of my friends, and I feel powerless at this point. I’ve spent years, literally, and many thousands of dollars trying to jump start a campaign, going to Steyer, going to other people, and pitching a case for it. I had an ad agency in New York that was willing to do it for less money and I had a whole plan of what we should do. I went all over. I must have met three hundred people, in this space, went all over the country, and couldn’t get anybody to [join in]. I probably raised forty thousand dollars in total. It wasn’t anywhere near what I would have to raise to get somewhere, and so I finally, I had to get back to work. I couldn’t do this full time because I couldn’t afford to, I still have to earn a living. So, I’m really frustrated, and most people I know have not spent, have not been that committed, have not done that much, and they feel powerless.

It seems that you are a proponent of people becoming active, and making smart energy choices, but not necessarily changing their fundamental lifestyles.

When I say they don’t need to change their lifestyle, what I mean is, we can still live in nice houses and drive nice cars. It’s just that the house have to be really efficient and the cars have to be really efficient, that’s all.

Kevin Anderson, deputy director of the Tyndall Centre, a UK climate change research center, gave up flying about a decade ago. It’s a statement, because he’s someone who’s always traveling to climate conferences where everyone else has flown in. Instead he’s taken the train, or gone by ship, every time. In LA, in a city where the infrastructure requires everyone to drive all the time, how do you factor in lifestyle choices? Can you just get an electric car, or do we need to drive less?

It’s a really good question. Los Angeles is a really difficult place to, I mean, as Los Angeles exists now, you generally have to have a car. On the other hand, technology and cars, you know, if we are talking about an 80% cut in carbon by 2050, cars are already there. I drive a Volt, you know, a Volt is an amazing invention. And the electric cars are amazing too, it’s just harder to get the range from them and not everybody can afford a Tesla, and the other ones don’t have enough range.

But with my Volt, the electricity that I use – because California is better with how it creates the energy – that’s the equivalent of one-hundred miles per gallon, when I am using electricity. When I’m using gas, I’m getting forty miles per gallon. And I drive forty miles a day, to and from work. That’s a very long commute. I know it’s ridiculous. Still, most days I use no gasoline at all.

Basically, I had a Volt for three years, I averaged a gallon of gasoline per week. One gallon per week. If everybody used one gallon of gasoline per week, we’d solve the problem. So, even if everybody has cars in Los Angeles, we already have the technology for cars that are efficient enough, and we have the technology for their houses to be efficient enough. Most of it is already solved, it just has to be promulgated on a mass scale.

Eventually there are bigger issues we have to deal with. In the next generation we have to deal with the whole issue of growth, you know? But I like to separate those things right now. I actually think it’s dangerous to talk about that stuff right now. By the way, in the same way I think it’s important to separate climate change from pollution and toxicity, because there are different levels of emergency, and if you are trying to create a constituency, the constituency for climate change can be a much bigger constituency. We have to separate all these issues. As important as all of them are, we have to separate them. I believe that strongly.

Getting back to what we opened with, I know you don’t work in advertising, but if you had fifty million dollars to launch an ad campaign, what direction would you go?

Well I think, first of all, the only answer to that can come from testing. In other words, I can tell you my instinct, but testing might show me that I am wrong, and that I have to use a different approach.

My instinct is that we need a combination of messages, because not everybody is the same, but what’s missing is…first of all, historically, America, as people have envisioned it, is a very masculine country, very aggressive, masterful, confident. And there’s been a dearth of “masculinity” in the messages about climate change.

The idea of American as a hero, America saving the day, America saving the world, being the strongest, being the biggest, these are very American messages. I want to reach the people who drive pickup trucks, big, f—ing F150 pickup trucks, and who don’t want to give up that sense of empowerment that makes you an American.

That’s what’s been missing in the messaging: that we could be great, we could be heroes, [and] we can solve this problem.

If you combine that with stories of people who are already doing it, already saving money, making money…I saw one thing somebody did about an entrepreneur in Texas, this guy was basically a rancher, who was making millions of dollars from wind because he’s got all this land. He just does it! The entrepreneurial spirit, it’s appealing to the things that are American in the broadest sense.

The idea of energy independence is not just a national idea, it’s a personal idea. Wouldn’t you like to be independent of these big a——-s who are taking your money? That’s an American idea. It’s the idea of making this exciting. It’s Reagan. Reagan had this great image of the shining city on the hill, and that’s what this can be.

George Marshall has a book about communicating climate change, and his big idea is that you need to segment the messaging and meet people where they already are. Create narratives that fit into their values – the values of mothers, or the guys who are driving pickup trucks.

Totally true, but, this is a problem we face in the movies all the time. The thing is that, the landscape of marketing has changed so much with the internet, and television has changed, everything is more niched than it used to be, but nevertheless, there have to be a few overarching messages that go out to fifty, sixty, seventy million people. And then, there can be these subgroups that you are appealing to for some reason or another. Mothers, worrying about the health of their children, young families, all kinds of groups, or demographic divisions that you have to appeal to. Of course you have to segment the message. And of course a lot of this has to be online, it can’t all be television. But, what they have found is, television is still the most effective thing. Online hasn’t beaten it because online is so diffuse that you can’t reach people in the same way. So, I’m sure he’s right, and I would, if someone gave me all the money I would apportion it to various amounts. By the way, now, in television buys, you can be incredibly specific about who you are targeting. So, you know, not everything has to be the Super Bowl. But I still think there are some overarching messages that will become a signature of this thing, and then you have other messages for smaller groups.

Is that typically true when you are marketing a big film? That there is sort of the one mass advertising campaign that you hope will get the fifty million people, and then online there’s more?

Yes, [the marketing team] decides what are the likely audiences for this film. So then, you got your TV marketing campaign, and then basically you are going to create two or three TV spots, and some of them will be different. There will be a TV spot meant for men, a TV spot meant for women, they’ll do that sort of thing. But, and then, there’s a whole thing about what are the magazines gonna want, what are the TV and the critics going to want? Is there a university constituency here and that sort of thing.

Those meetings are actually quite remarkable. You sit in a room, and there’s forty people around this huge table, and they all have different areas that they deal with, and they all have ideas about how they are going to reach people that they have to reach, and it’s quite an extraordinary discipline. It’s a very complex, yet highly developed art form, marketing. I’ve always been incredibly impressed when I go to those meetings. I go, “Wow, these people know their s–t.” And it works.

What do you think that young people who care about climate change should be doing?

Oh my God.

That is a big question.

Well I think the answer is they have to be in the streets, you know? But there’s no way for them to do that right now. That’s the problem, that’s the seven chickens and eight eggs thing, you know?

There’s a sense of fatalism that I see in this generation that wasn’t true of mine. That they were raised to feel that they were powerless in a way that upsets me. And yet they are passionate. And I see a change happening, but it may not be the right change. I have two children who are millennials. I know all their friends, and I see several things at work. I think the knock on my generation was that we hovered over them too much, we protected them too much, we gave them too much praise, all that stuff, all true, but what’s clear is that the generation was not ruined by that. What I see is a whole bunch of these people with that initial shock of, “Oh f–k, this is what the world is like? This is terrible!” And then they go, okay, and they figure out how to impose their will on it. Because they do have a very good sense of themselves, and they are strong-willed, and I just see a lot of people saying, “All right I’m gonna make my way.” I think that’s great.

What I fear is that the same thing’s going to happen that happened with my generation. My generation was incredibly activist in the 1960s, and then, everyone got scared when they got into their twenties, and said, “My God, I’m gonna die, I’m gonna starve,” and they just left it all behind and became materialistic. And I fear the same thing happening to the millennials. We thought we were omnipotent, we thought we could do anything, and then we went, “Oh, Holy S–t, no we can’t.”

Most millennials grew up, I think, feeling like there were a lot of things in the world that were really awful that they couldn’t do anything about, and so many kids have said to me it’s so hard to see what the future’s going to be like, and there really wasn’t a belief that there was going to be a great future. And that’s upsetting. So, I wish I saw that zeal, that sense of omnipotence, that we are going to change the world, we are going to make the world do what we want it to do. I wish I saw that, because, boy that’s what we need. That’s why we need a million people out on the streets, that’s what we need. But they can’t do that unless there is a whole command structure for how to do it, [and] what the message is, and all that stuff. Tell your friends, and tell Tom Steyer, that he’s gotta learn from the Koch Brothers. I wish there was somebody out there, who was willing to pay for a movement, because that’s what it’s going to take.

Portrait of Marshall Herskovitz by Columbine Goldsmith