As a series of posts on City Atlas have shown, the storm that swamped New York on October 29th pushed climate change onto the national agenda in a way that no other weather event has.

“You can’t say any one single event is reflective of climate change,” William Solecki, the co-chairman of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (and adviser to City Atlas), “But it’s illustrative of the conditions and events and scenarios that we expect with climate change.” (NYT, 10/31/12)

In fact, a NY Times profile of Dr. Solecki, written a decade earlier, opened with these prescient details —

“SITTING on Bill Solecki’s desk at Montclair State University was a study outlining the probable effects of global warming toward the end of the century: more frequent severe winter storms, sending floodwaters surging into such places as Jersey City and entrances to the Hudson River tunnels.”

Climate change adds moisture to the atmosphere, which suggests that more frequent and more extensive coastal flooding is in store for the New York area, whatever the strength of any oncoming storms. Other factors behind our region’s changes include warmer oceans, which add energy to tropical storms, and a diminished jet stream that may make the path of those storms different that they were in the past.

Dr. Solecki, and his partner in chairing the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), Dr. Cynthia Rosenzweig, shared their thoughts on a panel in the New York Times on whether, and how, the city should protect itself:

“Now that New York has experienced devastating coastal flooding, how can we recover and rebuild in a way that will enable infrastructural resilience to inevitable future storms, while minimizing a loss of life and livelihoods? Both ‘hard’ engineering interventions – like sea walls and innovative subway and tunnel closings – and ‘soft’ approaches – like reconstructed wetlands and smart designs for coastal communities – are needed.”

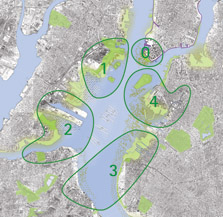

The idea of a ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ approach reawakens a forward-looking exhibition called ‘Rising Currents: Projects for a New York’s Waterfront’ that addresses this urgent question. It was collaboratively organized by the Museum of Modern Art and P.S.1 contemporary art center in 2010. Five multidisciplinary teams of architects, landscape architects, engineers, ecologists, and artists were challenged to re-envision areas of coastlines around the city; and this article is particularly focusing on lower Manhattan, which is Zone 0, the New Urban Ground. Here is a brief reintroduction to this innovative thinking about the future of the city.

1. Background

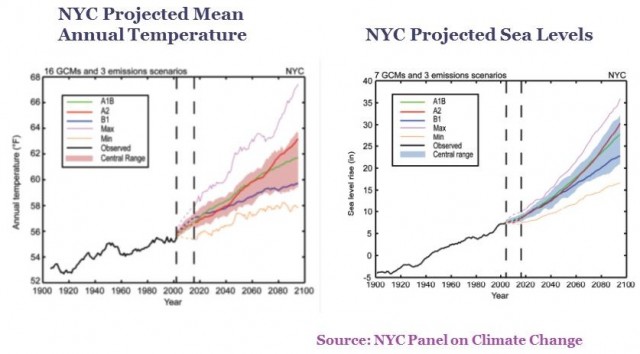

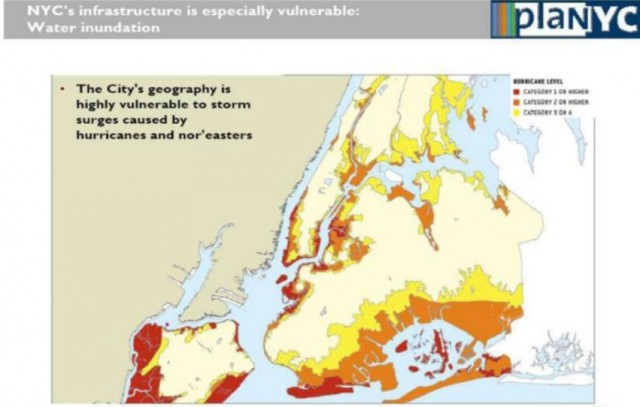

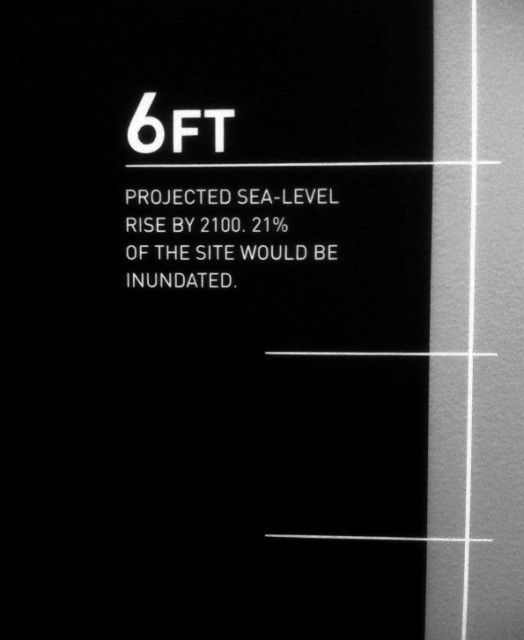

New York has the longest urban waterfront on Earth, with 500 miles. If sea level continues to rise, a huge expanse of coastal land would be inundated. Recent studies on climate change continue to produce more alarming figures, as rising seas create a higher baseline for future storm surges. The projected sea-level rise by 2080 is 2 feet, under normal conditions; in a Rapid Ice Melt Scenario, the rise in sea level would be doubled, according to “Climate Change Adaptation in New York City: Building a Risk Management Response,” the 2010 report prepared for the city by the NPCC.

Beyond sea level rise, there would also be more frequent and violent rainstorms that further put the city in danger of inundation. Manhattan used to have marshy edges, but those have been gradually erased since 1600s, when Dutch colonists built docks to facilitate trade, fortifications to prevent attack, and seawalls to protect the growing city from its watery lifeline. To make matters worse, current seawalls will not be able to withstand the predicted storm surge level.

2. Prospective Plan

Combining soft and hard solutions, New Urban Ground is a new paradigm for city infrastructure in Lower Manhattan. Normally, the city is crowded with mass concrete with dark surfaces that absorbs heat and generate urban heat-island effect. In the plan, the area is paved with a mesh of cast concrete and plants selected for their tolerance to pollution and saltwater. These porous green streets act as a sponge for rainwater in a new organic system designed to respond resiliently to daily tidal flows and occasional storm surges

i) Coastline

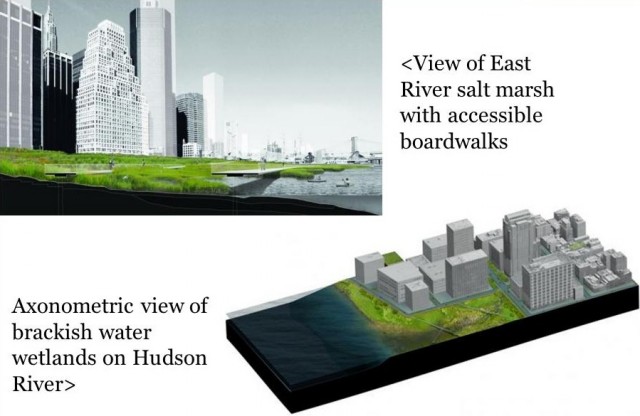

New Urban Ground cuts into the island and created urban estuaries; including upland parks, freshwater wetlands and saltwater marshes, which make the shoreline a new, continuous ecosystem. The urban estuaries supporting saltwater and freshwater wetlands alternate with areas zoned for development, creating a balance between economic and ecological sustainability. Streets within the storm-surge flood zone are engineered for 3 different water-carrying capacities: absorption (Level 1), distribution (Level 2), and retention (Level 3). In southernmost tip of Manhattan, there is the Battery Breakwater which is a field of islands, constructed of sediment-filled geotextile tubes and designed to moderate the forces of storm surges, in which located in a shallow saltwater marsh. The East side of lower Manhattan is extended with landfill by one block to create an esker, or ridge, parallel to the shoreline, as well as a park and a saltwater marsh. A linear forest below street level runs along the East River to Brooklyn Bridge, providing a defense from storm surges.

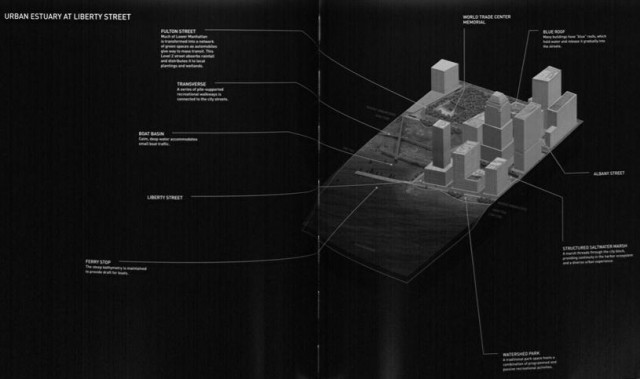

Consider the urban estuaries, at North Moore Street, a saltwater marsh mitigates the force of incoming water in the event of a storm surge because it is a Level 2 street designed to carry runoff and storm surge flooding off the land and out into the harbor. At Liberty Street, the steep bathymetry of the harbor necessities cuts into the urban landmass to create shallow water. Shallows support the plant and animal ecosystems that ameliorate the impact of upland runoff. A series of elevated walkways creates a platform for recreation, allowing people to occupy the estuary without disruption the natural habitat. The urban edge is raised according to the heights of tide. There are also features like Watershed parks, ferry stop, boat basin, and blue/green roofs that hold water and release it gradually into the streets. Much of the area is transformed into a network if green spaces as automobiles give way to mass transit. This type of Level 2 Street absorbs rainfall and distributes it to local plantings and wetlands. There are even pile-supported walkways connect to the city streets called transverse, and structured saltwater marsh threads though the city block, providing continuity in the harbor ecosystem and a diverse urban experience.

ii) Infrastructure, Roads and Transportation

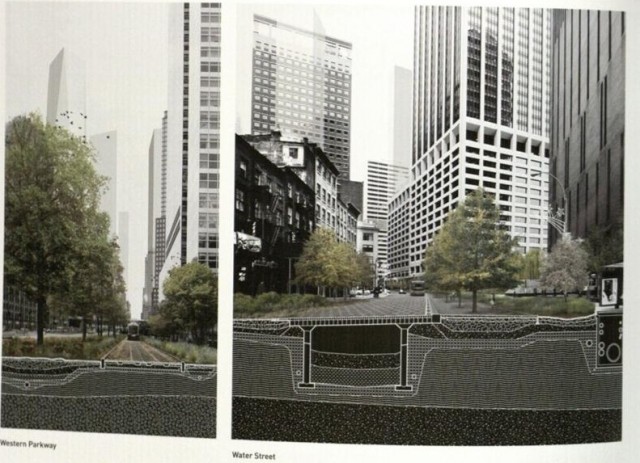

West Street is reconstructed and renamed Western Parkway. Much of its width is given over to green space, a light-rail transit loop, pedestrian walkways, and bike paths. Water Street is a level 3 street which runs parallel to the shoreline. It is designed to hold storm-surge volume and drain back to the harbor. The Plants in these zones are selected for their capacity to withstand higher levels of salinity due to inundation from storm surges. Coenties Slip provides a first line of defense against a storm surge.

- Image: Rising Currents

In Broadway and Hanover Square, the public and private utility infrastructure is housed in accessible waterproof vaults beneath sidewalk, in which the vaults consist of private utilities (dry system, like electricity and telecommunications) and public utilities (wet systems such as water, gas, and sewers)

The exhibition demonstrates great examples in constructing a flood-tolerant city with both hard and soft approaches. I believe we can make this city more sustainable.

“I’m hopeful that not only will we rebuild this city and metropolitan area but we use this as an opportunity to build it back smarter. There has been a series of extreme weather incidents. That is not a political statement; that is a factual statement. Anyone who says there’s not a change in weather patterns I think is denying reality… We have a new reality when it comes to these weather patterns; we have an old infrastructure, and we have old systems, and that is not a good combination. That’s one of the lessons that I am going to take from this, personally.”

-Governor Cuomo, October 30, 2012

More information can be found in articles at Architectural Record, Metropolis Mag., and Artinfo.