![A few degrees of warming is enough to melt a large amount of polar ice and cause substantial sea level rise. [Photo: http://wonderopolis.org]](https://newyork.thecityatlas.org/wp-content/uploads/Wonder-87-Polar-Ice-Cap-Static-Image2.jpg)

The letter is part of a broader campaign, and readers can add support by signing. So far, over one million people have signed (including the City Atlas interns). From the letter:

Human-induced climate change is an issue beyond politics. It transcends parties, nations, and even generations. For the first time in human history, the very health of the planet, and therefore the bases for future economic development, the end of poverty, and human wellbeing, are in the balance…

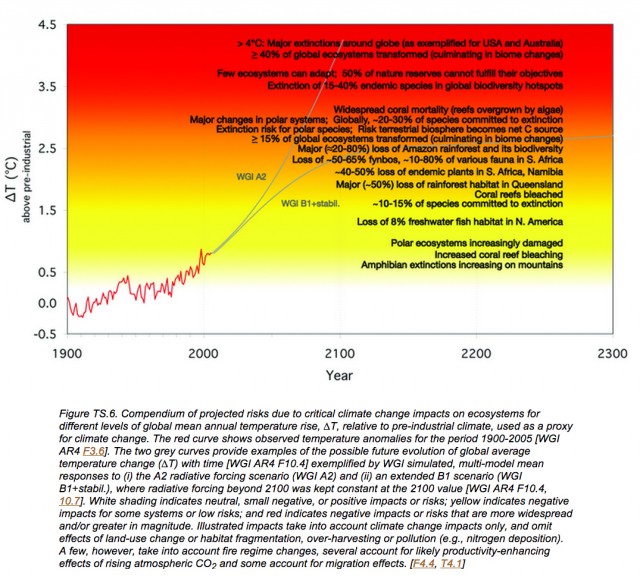

The world has agreed to limit the mean temperature increase to less than 2-degrees Centigrade (2°C). Even a 2°C increase will carry us to dangerous and unprecedented conditions not seen on Earth during the entire period of human civilization. Various physical feedbacks – in the Arctic, the oceans, the rainforests, and the tundra – could multiply a 2°C temperature increase into vastly higher temperatures and climate disruption. For this reason many scientists and some countries advocate for 1.5°C or even stricter targets.

To give up on the 2°C limit, on the other hand, would be reckless and foolish.

The recently released film DISRUPTION also contains an explanation of the 2°C target, excerpted in the clip below:

John Sterman of MIT keeps the target in perspective in the clip: “Two degrees is a round number…that would be safe-er, but we’ll still have substantial climate impacts.” But the mark provides a goal for the world to shoot for.

The Sustainable Development Solutions Network not only pushes for the 2°C target, but has a recipe to get there. Their report “Pathways to Deep Decarbonization” was presented to the UN in July; the report includes practical steps for individual countries to reduce their carbon demand, and thus a way for the world to stay within the maximum of 2 degrees of warming. The “Pathways” proposal, and the challenge it represents, have been well summarized by Eduardo Porter in the New York Times.

So far, there has been an increase of about 0.8 degrees Celsius (or 1.44 °F) in the average global temperature due to greenhouse gases. Climate models predict that the greenhouse gases we have emitted up to the present will continue to increase the temperature by up to 0.8° C more, adding up to a total warming of 1.6° C. Because our existing infrastructure runs on fossil fuels (detailed in an excellent Dot Earth post), it’s inevitable emissions will continue for years to come even if we work fast, but if our infrastructure shifts to clean energy rapidly, a 2 degree target is still in reach, according to the UNSDSN report. The energy shift, and behavioral shift, necessary for a 2° C limit has been discussed earlier in City Atlas.

In light of the changes already observed in the world, and projections of further change, many scientists and governments, including those at the Copenhagen climate conference in 2009, have decided on 2° C as a desired limit. It has been stated that a change exceeding this would have devastating consequences for the planet and civilization.

[It’s worth noting here that 2° C was originally conceived as a ‘ceiling,’ and now it’s becoming a baseline — with many economists and scientists expecting a higher target will be implicit in negotiations. This process of ‘moving goalposts’ in climate reporting is well described in a recent, important essay from Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.]

Beyond the science and policy, to the general public, there is a mystery: on paper, the changes in temperature may not appear drastic.

[pullquote align=”right”]It’s easy to wonder: how could such a small change in temperature cause such large environmental changes? [/pullquote]2 degrees Celsius is more familiar to American audiences as 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. This is the difference between, for example, 68° F and 70.6° F, or a warm spring day versus a slightly warmer one. Yet it’s well known that climate change poses massive dangers to our communities, and to maintaining geophysical features of the planet, like ice at the poles, our coastlines and farmland.

So it’s easy to wonder: how could such a small change in temperature cause such large environmental changes? If we’re only talking about temperature differences in the range of a few degrees, why is climate change such a problem?

It’s a reasonable question on the surface. However, the reality of climate change is that an average global increase of a few degrees means much more than slightly warmer days around the world.

First, one must remember to distinguish between heat and temperature. Heat is energy – temperature is the average amount of that energy per the amount of space, and therefore it is partly dependent on space. If a temperature change happens in a larger volume, it requires more heat. For example, it would take a much greater amount of heat to increase a gallon of water by 1° C than it would take to increase a teaspoon of water by 1° C. (And it takes much more energy to heat up a pot of water than to heat up the equivalent amount of air. This is why most of the added energy from global warming is being absorbed by the oceans; they have a vastly greater capacity to absorb heat.)

Likewise, a temperature increase – even an ostensibly small one – spread throughout the atmosphere and oceans of the entire Earth entails a huge amount of heat that was not present before. And all this new heat has already begun to have profound impacts on the entire weather system, which is driven by interactions between the oceans and the atmosphere.

The heat will contribute to the formation of storms, making destructive extreme weather events more common around the world. There has already been an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events in recent years, and many scientists have stated that this is at least partly due to climate change. The entire energy level of the system has already climbed significantly, a change set in place for centuries to come.

Another point that must be remembered is that an average global temperature increase does not necessarily mean that the temperature will increase by the same amount in all locations. The key word here is “average” – the temperature change is wide-ranging around the world, and the average global temperature change is only in the middle of this range. Land warms more than ocean; temperatures change more dramatically farther from the equator.

The Arctic and the Antarctic Peninsula have thus increased in temperature far more than the global average. These are also some of the most sensitive areas to temperature changes, due to having a large amount of ice. The difference between ice and liquid water is as simple as below vs. above 0° C (32° F), and any temperature increase at all in these areas will increase the amount of melting ice. The rapidly melting glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica are examples of the effects.

Even if the average global temperature change may seem low, the temperature increase currently happening at the poles will melt enough ice currently on land to flood coastlines around the world. According to James Hansen, former director of climate research at NASA, the history of Earth’s climate indicates that just a 2 degree change in the average global climate, over a span of centuries, would increase sea level by more than 20 feet – a change that would place many currently inhabited communities around the world underwater. As most of the world’s large cities are on or near coasts – including, of course, New York and Washington, DC – this will affect a large portion of the world’s population.

There are also certain ways in which initial temperature increases will make way for other ones in what are called positive feedback loops. One feedback loop relates to water vapor, which is actually the atmosphere’s most potent greenhouse gas. Humans do not directly release water vapor, but the warming temperature from the emissions of other greenhouse gases will make more water evaporate in the atmosphere, meaning that the temperature increase will itself cause more temperature increase. For another example, CO2 and methane are currently trapped by permafrost in the world’s tundra, and if the permafrost melts due to climate change, these greenhouse gases would be released and further contribute to the problem. Also, James Hansen has stated that an increase of about 2 degrees could cause droughts that would devastate the Amazon Rainforest, and the decomposition of its plants after they die would release a large amount of CO2, raising the temperature further.

There is also a difference between normal day-to-day temperature variation and the shifting of the entire temperature range in one direction. When the average temperature increases, the range of typical temperatures increases with it. This will make extreme temperatures more frequent – for example, if very hot days are defined as days over 90° F, a higher range of typical temperatures will mean that days over 90° F are more frequent.

[In a mark of how unpredictable effects are, it’s speculated that the cool summer of 2014 in the Northeast US may have resulted from a shift in weather patterns over the Arctic, which has warmed. California had the hottest start to the year on record. The planet as a whole has also warmed in 2014.]

These temperatures can have adverse effects on people’s health, especially for elderly people and people with illnesses. Although this will be a problem in temperate areas, it will be most dangerous in areas that have often been affected by drought, such as many parts of Africa. In these areas, every degree added by climate change will make extreme heat more frequent and make droughts more threatening.

Daniel Bader, a climate scientist with the Climate and Urban Systems Partnership, explains this concept well: “Basically, I want you to picture a bell curve… it really illustrates this point that a small shift in the mean makes a big difference in your extremes… You have a given threshold at which impacts occur, and let’s say that it’s days with high temperatures above or above 90 degrees. And by just shifting the mean climate, let’s say, 2 degrees Fahrenheit… any day that the previous climate was 88 degrees, if you bump it up 2 degrees, you’re at that threshold. And you can see how quickly those extreme events, the number of days above that given threshold, are going to add up, just by making a small incremental change.”

Bader also describes what this means for New York City, “The summer of 2010 was a very hot summer… there were 37 days with high temperatures at or above 90 in Central Park. That’s two times the current average. We usually get 18 days at or above 90 Central Park. And what we experienced in 2010, the 37 days, is approximately the number of days the average year in the 2050s may have, based on our projections. So the real hot years in our current climate may become more of the normal out towards the middle of the century.”

Most organisms can handle temperatures that are sometimes higher and sometimes lower than what they are adapted to. However, when the temperature range increases, most days will be like hotter days in the climate system that the organism evolved to live in. And organisms will not fare well in conditions that are consistently removed from those they are adapted to. These organisms include both wildlife and the agricultural crops that all people rely on. (Climate scientist Richard Alley discusses small rises in temperature and the effect on crops, here.)

Wildlife and farming are especially crucial concerns in the tropics, where the majority of the world’s species and many people live. In the tropics, instead of the temperatures changing frequently with the seasons, the temperature is usually quite constant throughout the year. If the temperature in a tropical area gets hotter than its usual level, even just by a few degrees, its living things will no longer be under their adapted conditions.

[pullquote align=”left”]To solve for climate change, we must work together with common purpose, which requires a shared understanding of the problem. [/pullquote]The change will also disrupt the area’s diverse ecosystems, which have already been very much reduced by humans. Agricultural shortages and failures will be more likely – and of course, people need agriculture for food. This concern is made even more pressing by the fact that many communities in the tropics are not wealthy and already struggle with food availability.

People cannot be blamed for wondering why a global increase of about 2° C is so worrisome, as it may not seem intuitive that this would be dangerous. Bader feels it’s important to connect the science and numbers to people, “People can relate to the impacts caused by extreme temperatures . . . During these heat waves, let’s say, transit services are interrupted, or energy demand causes brownouts, then they can relate to it, they remember when these events happen. This increases their understanding of how a greater number of extreme events is going to impact their daily lives.”

Delving into what 2 degrees of change really means on a worldwide scale reveals the diverse and serious threats it creates. At a time when we must start making changes to mitigate and adapt to climate change, people must work together with common purpose, and common purpose requires common understanding of the problem at hand.

Another economic analysis of the path to a safe (or ‘safer’) 2°C climate has now appeared from the New Climate Economy project, which calls for a sweeping realignment of the $90 trillion expected to be invested worldwide in infrastructure over the next fifteen years.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.