Given the imperative of fast action on climate, 2018 must be a year that prioritizes decisions rather than simply adds more detail to a story we already know. 2017 already brought three books that tell us enough about what we need to do and why: Peter Kalmus’s Being the Change, Brett Favaro’s The Carbon Code, and Jeff Goodell’s The Water Will Come. Those three stand out among dozens of excellent books written on the climate crisis, and we’ll have reviews of each in coming weeks.

But an unusual book from 2014 has been among the most powerful reads in our office at City Atlas. It’s a science textbook, an art project, and a personal story rolled into one, and it is here reviewed by Truly Johnson.

From straightforward explanations of climate science, to the effects of rising temperatures, to possible solutions to the climate crisis, Philippe Squarzoni’s graphic novel Climate Changed is a comprehensive look at the existential problem the world faces today. It is also a deeply personal story; Squarzoni takes on the challenge of creating the book in order to understand climate change himself, and to learn how it impacts his own life. The science discussion and the personal thread come together in surprising ways, creating moments that hit the reader with revelations of both knowledge and emotion. Here are five of those moments that I can’t seem to stop thinking about.

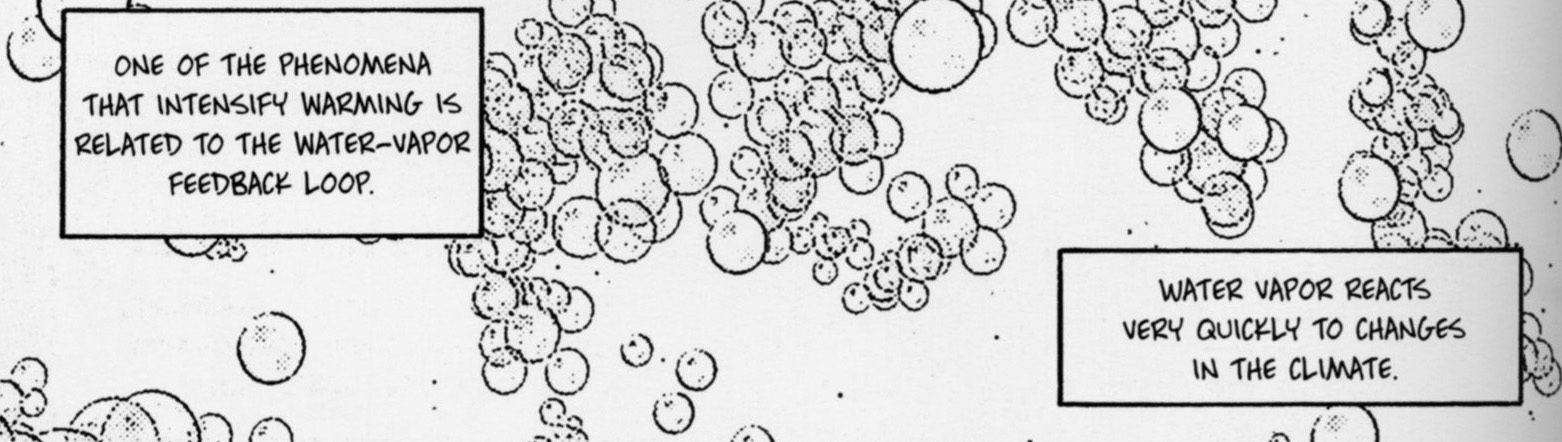

Positive feedback

One of the most terrifying aspects of climate change is its ability to continuously fuel itself further. This is illustrated in Squarzoni’s very visual definition of positive feedback, on page 120. It shows one bubble of water vapor, a greenhouse gas, rapidly multiplying. The text provides the explanation: more warming causes more water to evaporate as water vapor, which in turn causes even more warming. It is a cycle that magnifies even small changes in climate, making them larger and more threatening. Across these pages Squarzoni goes on to explain other positive feedback loops: how warming leads to decreased storage for carbon in the ocean, decreased oxygen production by plants, more forest fires that release CO2, and many other effects that further propel warming. With every example of positive feedback, the situation seems more dire. It’s one thing to say that certain actions of humans are changing the climate. That explanation offers a deceptively simple answer – just stop taking those particular actions when the situation gets particularly bad, and poof! The whole world is fixed. But Squarzoni pokes a hole in this simplistic view with every positive feedback cycle he explains. These explanations emphasize the simple fact that if we do not stop our destructive actions soon, nature’s positive feedback will magnify them to a point of no return.

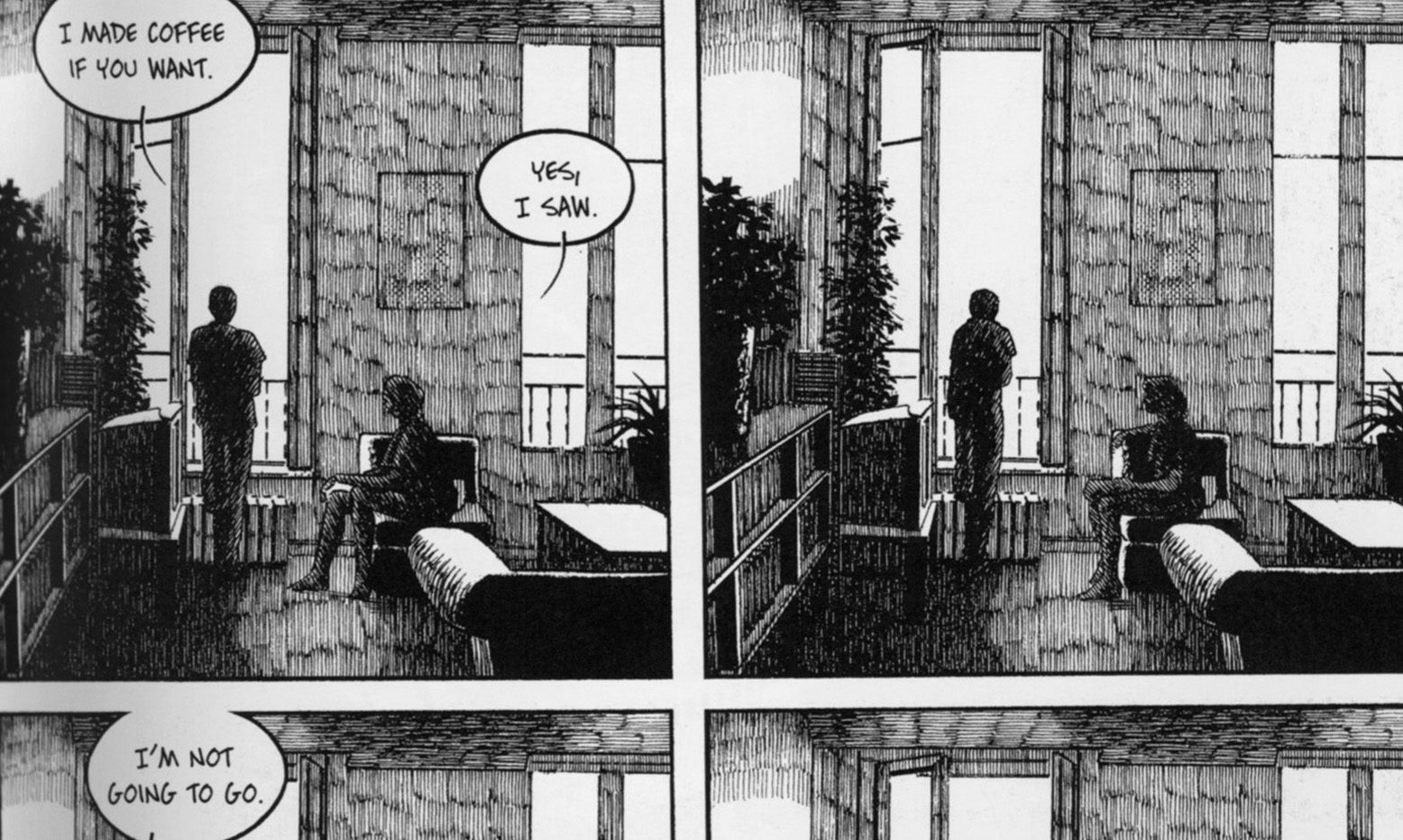

Difficult decisions

You may think that a book about such a scientific topic as climate change can’t have something as literary as character development. But Climate Changed does, as Squarzoni reexamines his lifestyle in light of the knowledge he gains on his quest to understand the climate. When Squarzoni is invited to a residency in Laos, he is initially excited about the opportunity. But as he learns about the high levels of greenhouse gases produced by air travel, by page 219 he is caught in a dilemma. Should he give up on a fantastic opportunity just to reduce his emissions? Or should he go anyway and turn a blind eye to the environmental effects of a plane trip? His answer is not immediately clear. We see his thought process as he goes back and forth: he doesn’t want to be a hypocrite, but the plane will take off whether he’s on it or not. A plane ride emits a large amount of CO2, but plenty of other people are emitting even more. He wants to travel, but he doesn’t want to doom the Earth. In the end, he decides not to go. That moment really caught me by surprise. It’s not often that you see anyone, even environmentalists, give up something that matters so much to them for the sake of the Earth. But in that bittersweet moment, Squarzoni does just that. It was a moment that made me proud of him, but also uncomfortable. Because if he can sacrifice a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, we all can sacrifice a little more for the Earth. Maybe the world is in such a dire situation now because we all refused be as selfless as Squarzoni did in that moment. It really made me think and look critically at myself and my decisions.

Useless biofuels

Anyone who has looked into renewable energies has probably heard of biofuels, fuels made from various agricultural goods. Obviously, there are flaws with a model like this, most notably that growing fuel means there’s less land for growing food. But all alternative energy sources have some flaws. And as biofuel advocates say, biofuels can fit into the existing infrastructure of fuel for cars. Before I read this book, I thought that biofuels could have at least a small role in the world’s transition to green energy. But on page 328, Squarzoni debunks the biofuel myth by simply laying out the numbers: it takes 0.9 gallons of oil to produce one gallon of biofuel, and the process of creating biofuels emits nitrous-oxide, an even more potent greenhouse gas than CO2. After reading this, the idea of biofuels seemed so ridiculous that I started wondering why anyone came up with it in the first place. It also made me wonder what other proposed “solutions” out there were in fact useless and only still around due to marketing and bad information.

Anyone who has looked into renewable energies has probably heard of biofuels, fuels made from various agricultural goods. Obviously, there are flaws with a model like this, most notably that growing fuel means there’s less land for growing food. But all alternative energy sources have some flaws. And as biofuel advocates say, biofuels can fit into the existing infrastructure of fuel for cars. Before I read this book, I thought that biofuels could have at least a small role in the world’s transition to green energy. But on page 328, Squarzoni debunks the biofuel myth by simply laying out the numbers: it takes 0.9 gallons of oil to produce one gallon of biofuel, and the process of creating biofuels emits nitrous-oxide, an even more potent greenhouse gas than CO2. After reading this, the idea of biofuels seemed so ridiculous that I started wondering why anyone came up with it in the first place. It also made me wonder what other proposed “solutions” out there were in fact useless and only still around due to marketing and bad information.

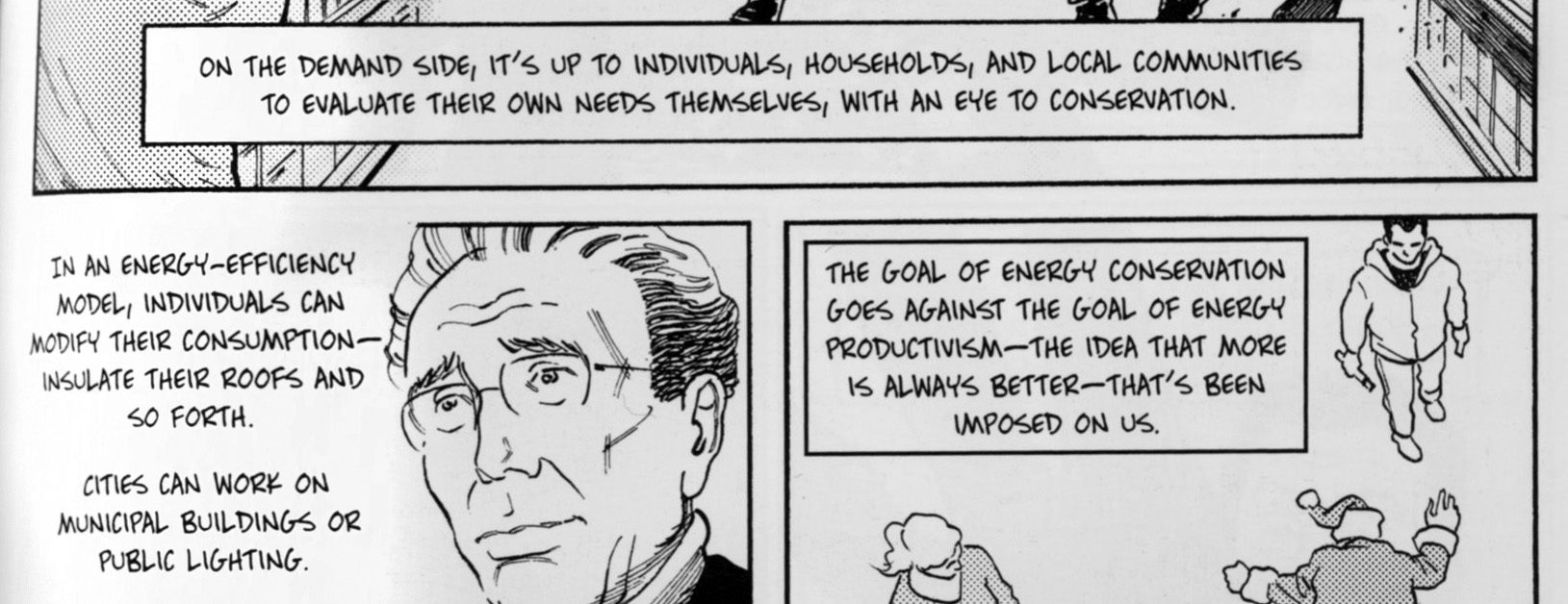

Our addiction to shopping

The section on consumerism and climate towards the end of the book was probably the part that stuck with me the most. On page 377, Squarzoni describes our consumption-obsessed society as a “Christmas story” where resources seem infinite and everyone seems happy. In reality though, Squarzoni makes it clear that overconsumption is at the heart of the climate problem, as well as the problem of economic inequality. He illustrates how many of our emissions come from consumption that is not strictly necessary and can certainly be reduced. One possible solution, according to Squarzoni and many of the people he interviewed, is to simply not consume so much. Squarzoni accompanies this idea with illustrations that show himself and his partner Camille destroying various symbols of consumerism like cars, consumer goods and Santa. Perhaps the strangest and most striking image in the book is that of Camille shooting at a row of Santas holding various products. It is a jarring display of violence in the middle of a book that mostly consists of science and interviews. It seems like there could be a variety of interpretations as to why Squarzoni chose that particular image. It makes you think. The way I see it, Squarzoni has established that the flawed system of capitalism depends on consumers continuing to overconsume. With his illustrations, he empowers the reader to play their part in dismantling this system: just reducing consumption of resources you don’t really need is the equivalent of stopping the Santa of capitalism. He is pointing out that in many ways, rethinking our purchases is a radical act, since our lifestyle is so based on consumption. But it’s possible and it’s powerful.

The end

The ending of Climate Changed could be described as depressing. Squarzoni admits that he does not believe people will make the necessary changes in time to prevent most of the terrible effects of climate change. It seems as if Squarzoni is trying as hard as he can to find some way to make the ending a little more uplifting. But he just does not see an uplifting solution to climate change that will actually happen, at least not in time. It’s really a wake up call. In order to fully combat this problem of climate change, we must, as a whole society, act now, something that looks next to impossible. Squarzoni tries to balance out the despair by explaining “just because the answer is filled with gloom doesn’t mean the question was pointless”. He wants readers to think about these issues, despite how hard they are to solve. The sad but somewhat open ending is almost not even an ending as much as a trailing off. It’s now up to the reader to continue the story using what they’ve learned. Squarzoni even says “I could be wrong”. It almost seems like a challenge, an invitation to the readers: not simply “I could be wrong”, but “prove me wrong”.