As cities grow greener and the urban framework works to maximize its environmental gifts like waterways and parks, certain questions must be asked. Cities in their beginnings were founded in naturally advantageous places such as near waterways, harbors, and fertile valleys among others. Today however, the most naturally gifted cities have fallen behind those places where human ingenuity has fostered a desire to constantly reinvent the urban fabric such that the once powerful connection between the city and nature has been broken. Modern consumers in urban areas choose largely to ignore where their produce, meats, construction materials, and other non-urban items come from. Furthermore, we also largely choose to ignore the fact that what we perceive as “natural,” or from nature, is quite often the product of human beings.

The terms “first nature” and “second nature” were first coined by William Cronon in his seminal work on Chicago, Nature’s Metropolis. Cronon uses “first nature” to define the purely natural aspects of cities, especially those god-given advantages that give some cities a leg up on others. A prime example of this is New York’s deep, one-of-a-kind harbor. “Second nature,” however, is used to describe those advantages that humans have created within the urban framework. Public transportation, street systems, and, most importantly, parks, are all “second nature” advantages in cities.

Take a moment to think about this. Many things that we consider most natural about our cities and our country (the greenbelts, the park systems, the green grass of the suburbs) would not exist in the true sense of “first nature.” In fact, the original grid plan for New York included one large park that was laid out so that the city would not totally override the natural state of Manhattan Island. That park, which was then military parade ground, would ultimately become Tompkins Square Park (and its current iteration is far from “first nature”). As the city grew outward towards uptown, it took “second nature” human efforts by city officials and urban landscape architects Fredrick Law Olmstead and Carl Vaux to create, rather than necessarily preserve, greenery in the form of Central and Prospect Parks.

While these parks impart a system of “natural beauty,” it is important to remember that they are as much the product of human ingenuity as they are products of nature. The tall leafy trees were carefully planted, the grass properly maintained at considerable cost, the manmade lakes (yes, they are not all natural) and countless other landscaping features were all designed to give New York and its residents yet another advantage, another way of solidifying the city’s place at the top of the urban hierarchy. Even the suburbs, which represent a compromise between rural and urban, were carefully laid out and landscaped. Certainly New York City, and Manhattan in particular, has changed greatly since its true “first nature” heyday in the early 17th century at the beginning of the Dutch settlement era. Because of this, we cannot truly consider today’s pockets of urban greenery as being the same “first nature” as the original Manhattan Island.

It’s a radical way of rethinking nature and the environment within cities. Is anything in the urban framework still truly “first nature”? Obviously there are some pockets where mother nature shines through in her true form across all five boroughs, but the overall lack of true “first nature” features in cities forces us to reconsider what we think of as natural within the urban landscape. In fact, some of the only places left largely untouched directly by man are in danger of pollution from the secondhand effects of urbanization. We must recognize that the things that we consider little oases of greenery are not natural. Rather, they are human products of an era in which small islands of nature could be actively placed within cities to make the urban habitat more livable. Furthermore, this realization forces us to rethink how we explore “nature” in an urban context.

The next time you go to a park, consider the human input required to maintain it, the careful planning of its undulating pathways and changes in elevation, the presence of thick green grass. This acknowledgement of the human element in “second nature” greenery does not necessarily have to decrease your enjoyment of such spaces. Instead, we must be cognizant of the fact that when we canoe down the Bronx River, our ability to do so is not necessarily a “first nature” ability, but rather the product of tremendous human ingenuity to restore, protect and maintain a quasi- “first nature” state. When we revel in the long bike path and the breeze biking down Riverside Park, we must remember that it took tremendous human effort for that possibility even to occur.

While we cannot and should not forget Mother Nature, it would be a disservice to urban environmentalists past, present, and future to assume that these natural elements were simply the products of “first nature”. To ignore the human element would be to forget how far we’ve come in making our cities organic and more connected to nature, and similarly to forget our tremendous ability to continue this trend towards a brighter, greener urban future.

Interesting links on the topic of NYC’s first and second nature states:

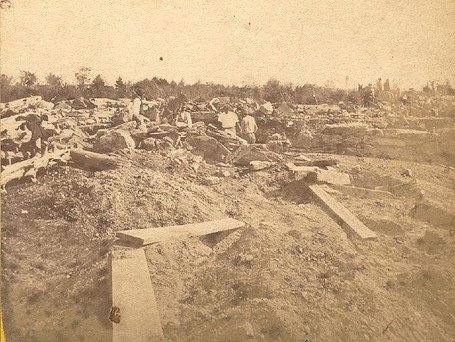

To see what New York City’s parks looked like before they became the islands of green that we know them as today, peruse the “Before They Were Parks” website provided by the Department of Parks and Recreation.

If you would like to explore Manhattan Island in its original “first nature” state at the time of the initial Dutch settlement, check out The Welikia Project, or pick up a copy of Welikia Director Dr. Eric C. Sanderson’s book Manhatta: A Natural History of New York City.

Enjoy Dr. Sanderson’s interview with City Atlas as well!