Last week, the New York Times hosted a thoughtful and wide-ranging event, the “Energy for Tomorrow Conference,” which showcased an array of panel discussions led by city planners, scientists, notable public and private experts, farmers, activists, and the mayor of NYC himself – all of whom discussed the current state of NYC as a center for progressive infrastructure and energy, transportation, nutrition, resiliency and green policy, while arguing their professional opinions of how to make NYC more sustainable.

Of the discussions, one of the more impressive – and rather extreme – conversations came from Klaus H. Jacob on waterfront storm resiliency.

Klaus Jacob is a geophysicist at the Earth Institute, Columbia University. During his one-on-one with NYT op-ed columnist, Joe Nocera, Jacob spoke on the measures of storm preparation that, in his eyes, NYC must adopt. Understanding that the climate around the greater New York area has drastically changed in the last decade or so, Jacob suggests three fundamental plans for effective storm resiliency:

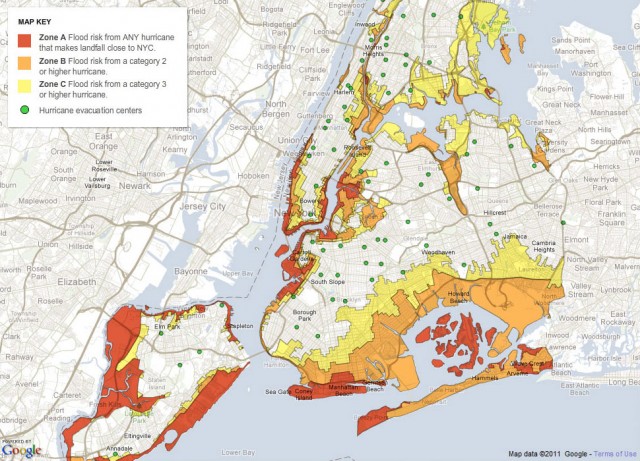

Storm protection – possibly the plan with the least impact amongst the three, yet just as important, to protect our coastlines by building and implementing surge barriers. Though some may argue that surge barriers simply pass on the amount of storm energy and surge to the adjacent coastlines that are unprotected by the barriers (which in the case of NYC, the unprotected areas would most likely be the Rockaways and Jamaica Bay area, both of which are, by average, low-income and financially at risk neighborhoods – which opens up a whole other philosophically socioeconomic ‘can of worms’), they would still help to protect the very vulnerable downtown areas of NYC, therefore saving money and resources on otherwise very high storm-repair costs.

Accommodate the water – “invite the water the way it wants to go, given the current landscape.” Klaus Jacob believes we should both figure out ways to channel storm water through the city while causing the least amount of damage, as well as retrofitting the buildings within flood-zones. To effectively retrofit these buildings, Jacob suggests that all basements and first- and second-level floors of buildings in these zones should be sealed off and used for parking only. By doing this, the city will have less damage to worry about during a storm on the scale of Hurricane Sandy; storm damage repair costs have the ability to be cut in half; and the only emergency response most of these buildings will have to partake in is evacuating the cars from these lots. Though at the cost of losing former rental space and real-estate value, it can be extremely beneficial to curb storm damage by sealing off and retrofitting the lower floors of storm-vulnerable buildings in NYC.

Another way to retrofit the urban landscape in order to accommodate for storm waters, especially within the downtown, high-rise areas of NYC, as suggested by Jacob, is to expand the NYC ‘High Line’ infrastructure. Jacob believes that connecting buildings with high lines, or walkways and transportation networks safe from rising waters, will significantly help in emergency response as well as continual functionality within the flooded areas. Connecting buildings with a walkable transportation system adds another level of resiliency.

Managed retreat to higher ground – Jacob’s most stressed – and radical – solution is to convert buildings located in high-risk, flood-zone areas into green spaces, while redeveloping our city with regards to topography; in other words, building on higher ground. Jacob believes the city should be working on re-zoning flood-zone areas as green, open, and/or undeveloped space, while zoning areas of higher elevation within NYC as high-dense residential and commercial areas. Though this plan would ultimately change the face of NYC and would surely find an enormous amount of friction and opposition along the way, Jacob suggests that flood-zone retreat would be the most economically wise decision in future NYC planning. He makes reference to a study by the National Institute of Building Science that developed a way to look at and compare the cost-effectiveness of flood-zone retreat to average coastal damage costs paid by FEMA mitigation funds. They established that “for every $1 spent in protecting your assets and your economy [in this case, by investing in flood-zone retreat], you get $4 back in not incurred losses.”

Jacob also suggests a policy for flood-zone retreat, targeted towards homeowners in coastal flood-zone areas, by imitating a popular land conservation policy model originally used for obtaining farmland in a reasonable, fair, incentivized way. He suggests that NYC creates a policy that allows the city to confront homeowners in high-risk areas, such as the Rockaways and parts of Staten Island, offering to buy their property. However, the homeowner is still allowed to either continue residency in the recently sold home until they are dead, or are given a generous amount of time to plan out their future residence. Though such a policy may be more time consuming and drawn out than desired, it can still serve as a very effective and publicly accepted strategy in acquiring flood-zone lands. Once in the possession of the city, the lands can then be ‘green-ified,’ made into public parks, developed into green buffers to further protect any adjacent neighborhoods, or even just left as undeveloped, open space.

Governor Andrew Cuomo has already installed a program that offers to purchase high-risk properties at ‘pre-Sandy market values,’ and offering double market values if a whole block agrees to sell. However, many of these homeowners have opted to turn down the offer, not catching the appeal that Cuomo had hoped for. Perhaps the governor should consider adopting Klaus Jacob’s more homeowner-friendly idea.

Jacob’s prescriptions for the more dire future forecasts may seem alarming and far-fetched now; at the same time, a reassuring note in the conversation was how many intellectual resources are now refocusing to plan a successful future for NYC.

- NYC flood-zone map; courtesy of Google Images/New York Times

2 Comments

Comments are closed.