The East River Esplanade, a 2-mile-long city-owned public park that runs from 63rd to 125th Street, was already being criticized by residents as being a bleak and poorly maintained public space when Hurricane Sandy hit, exposing the vulnerability of the entire waterfront. Swollen harbor waters swamped the upper section of the park and washed into East Harlem; now, attention turns to a complete reimagining of the shoreline along this neglected stretch of Manhattan.

Preliminary plans for renovating the Esplanade were actually in the works before the storm; the Department of City Planning drew up a proposal for redevelopment of the East River Esplanade as a part of Vision 2020, which aims to improve access, enhance pedestrian connectivity, and create waterfront amenities for public enjoyment and recreation, while bolstering the city’s resilience in the face of extreme weather events.

To add momentum to the public drive for a new park, CIVITAS, a community-led organization focused on neighborhood quality of life in the Upper East Side and East Harlem, recently held an extensive panel discussion on the future of the East River Esplanade; the talk was presented at the National Academy on Fifth Avenue.

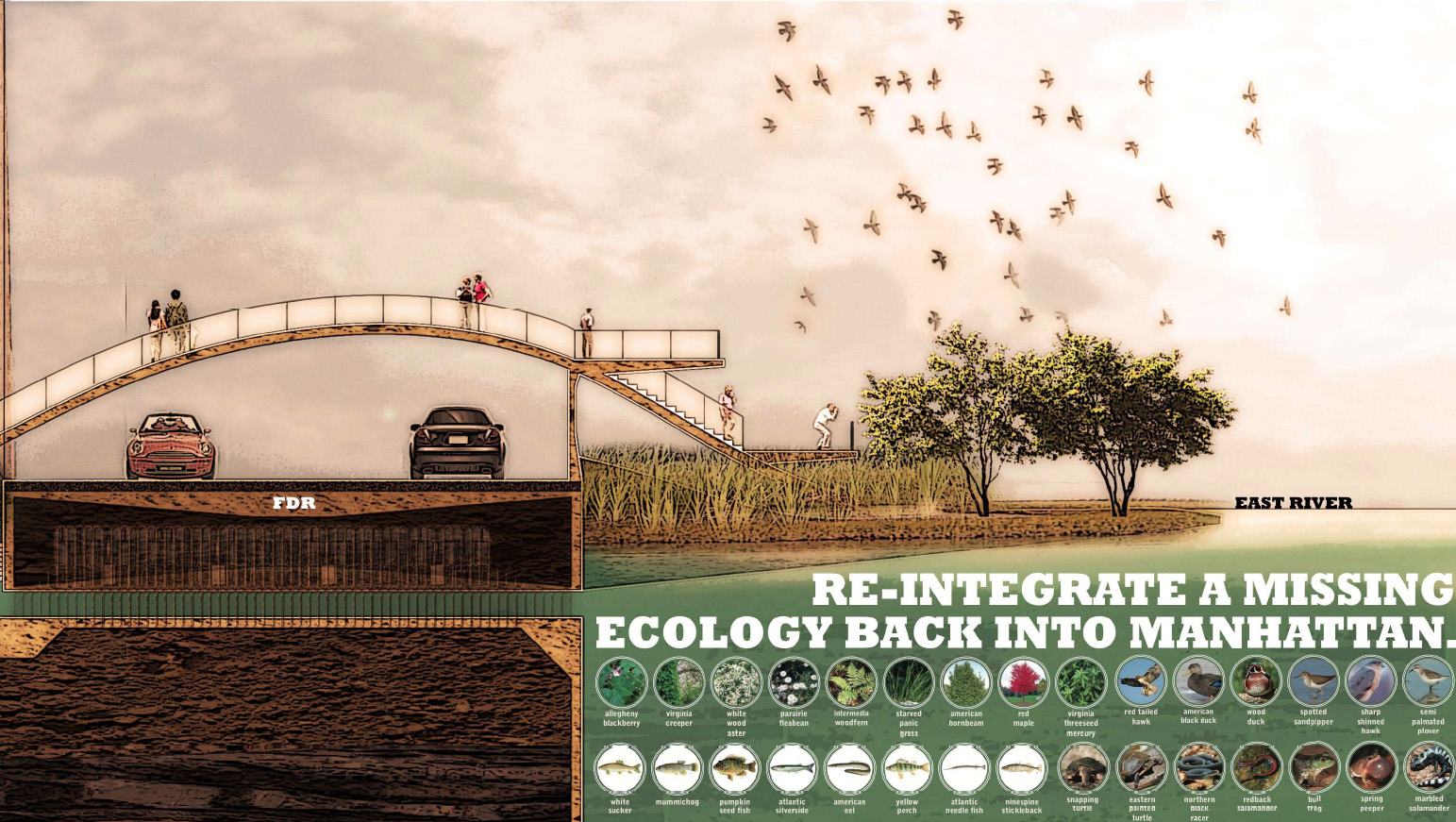

CIVITAS has long been an advocate for a better waterfront park, hosting several community visioning events and, during 2012, a notable design competition, for which the winning entries were exhibited at the Museum of the City of New York. (Detail from the first place concept, by Joseph Wood, is shown at top of this page.)

The group on stage at the October panel included architects, planners, designers, artists, and environmentalists, who shared sometimes competing ideas for ways a new public space can serve the city and the natural environment.

The CIVITAS panel discussion began with a presentation by SHoP Architects founding partner, Gregg Pasquerelli. SHoP has waterfront projects in two locations—Mitchell Park and its Camera Obscura sculptural installation (in Greenport, NY), and the East River Esplanade South and East River Waterfront/Pier 15 (South Street Seaport in Manhattan)— which were shown as examples of how a waterfront site can provide social and recreational space and be adventurous at the same time.

SHoP’s work shows clever space utilization in the double-decker green-roof piers at Pier 15, as well as attractive lighting strategies and seating arrangements—red ceiling lighting which help to create a more romantic space at night, and waterfront bar-stools that appeal to patrons who may wish to read, eat and drink, or simply converse with friends over a stunning view of Brooklyn and downtown Manhattan.

In Greenport, NY, a new town park encouraged community interaction and participation, added residential appeal, and fostered a real-estate boom. SHoP’s work relies on mixed-use design strategies to help attract a wider audience, fitting the recreational needs of a more diverse population. The examples also showed smart funding strategies, specifically in the East River Esplanade South project, where air rights located under the FDR Drive are being sold in order to help pay for project development.

[pullquote align=”left”]Panelists praised experimentation, and cultural awareness[/pullquote]

Charles Birnbaum, Founder and President of The Cultural Landscape Foundation, followed SHoP’s presentation by asking: how do we measure success in a post-Sandy situation? There is always an emphasis on environmentalism and aesthetics, but Birnbaum argued that culture should have an equally important place in the conversation; that people should be looking at development with the goal of turning a project into a “new ‘World Heritage site”; and that attention to culture in development is the difference between a successful project and just an average project.

Birnbaum warns us of the homogeneity of landscapes and development, but also praises the level of experimentation that seems to be occurring in the last decade where developers, designers, and architects are increasingly moving away from homogeneous designs and concepts. He asks designers, architects and planners to incorporate culture and history into their projects, as to teach people “how to see and value landscape and landscape architecture in a way that they are hardwired to look at architecture in the built environment.”

Birnbaum ended his comments with the “Four – C’s”—Collections, or the living and non-living in a given area; Community, or the context in which these collections work and play with each other; Containers, the buildings in these spaces; and Context, the physical and historical setting—the elements he believes are important for successful landscape developments.

Community involvement and participation became the next area of focus as the Director of Waterfront and Open Space of New York City’s Department of City Planning, Michael Marrella, took the floor.

Community involvement and participation became the next area of focus as the Director of Waterfront and Open Space of New York City’s Department of City Planning, Michael Marrella, took the floor.

“Do we have the waterfront that we want going forward?” In order to get the right answer to this question, according to Marrella, community participation is completely necessary. And as a result, the Department of City Planning’s Vision 2020: New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan was created from a year-long public planning process that entailed going out to each community in proximity to a NYC waterfront and inviting them to participate in organized workshops, where the communities were not only asked what they want out of the waterfront, but also what it would take to get there.

[pullquote align=”right”]Why does it take so long to build a park in NYC? Multiple agencies, but also public review.[/pullquote]

Marrella emphasized that public outreach works to challenge the planning process to serve the community best, rather than assembling the public for the purpose of creating lengthy, impossible wish lists. Marrella also brought up the thicket of environmental and waterfront regulations and the “horror stories” that come with them, where 6-month projects on paper turn into 8-year projects in reality due to permit wait times and other delays, and how there needs to be a more predictable, reliable, and efficient process that avoids these unwanted setbacks while making sure not to lower our environmental standards.

As in all well-rounded panel discussions, Al Appleton, former Commissioner of the New York City Department of Environmental Protection and Director of New York City Water and Sewer system, presented contrasting viewpoints on how to manage the East River Esplanade. Instead of focusing on building and development, landscape architecture and housing (part of the City’s master plan for the waterfronts also includes waterfront housing), Appleton urges that we reclaim the waterfront; but that we reclaim it not to serve real-estate purposes or improved apartment views, but rather to reintroduce nature to the waterfront.

[pullquote align=”left”]A call for reintroducing nature to the waterfront along the Upper East Side.[/pullquote]

Appleton believes that, if resiliency is a priority, planners will recognize that reestablishing nature at the water’s edge is the most effective method available. Appleton submits three mandates on how to deal with the East River Esplanade (and the rest of the city’s waterfront, for that matter): 1) there should be absolutely no new high-rise development on the waterfront, 2) natural areas on the waterfront should be reproduced and restored, such as Jamaica Bay and the Rockaways, and 3) the FDR Drive should be transformed and retrofitted in order to make way for a more natural coastline—he even suggests getting rid of it all together, which is a remarkable suggestion as most plans take the Robert Moses-era roadway as a given.

Appleton also critiques Marrella’s reference to the “horror stories” of the regulatory process, where 6-month projects turn into 8-year projects. Appleton argues that the political process is necessary; added wait times usually include more community participation and involvement, and that communities should be wary and skeptical of fast, steam-rolled development projects, as they tend to ignore civic consensus.

As the last presenter, Cecilia Alemani, Curator at High Line Art, spoke of the importance of art in public spaces. She updated the audience on the multiple types of media that are currently circulating in the High Line Park, as well as how the High Line is creating new concepts for parks and reinventing the art space. Along with commissioned work, the High Line has introduced a number of performance works, as well as interactive and engaging video projections — all of which, Alemani suggests, should be taken into consideration in the new East River Esplanade. And with the incorporation of art into the park, the esplanade can better address the cultural needs that Birnbaum mentioned earlier in what truly makes a successful waterfront space.

To wrap up the entire panel discussion into one coherent message, it might sound something like this: In order for the East River Esplanade that runs from 63rd to 125th Street to become a truly successful public space that serves the needs of the community, it must have a daring yet smart design that integrates art and culture, and meets the concerns of the community and the environment. Given the new realities of climate change, this space must play a role in coastal protection, but also should simultaneously attract and appeal to all people in a social and recreational context.

The vitality of the discussion and the depth of the ideas on the table show how New York continues to enjoy a renaissance in the confident and inventive design of public space.

If these weights and measures are taken during the redevelopment of the East River Esplanade, it seems that the Upper East Side and East Harlem will have a new, visionary way to get to the water’s edge in their neighborhoods, with a public amenity that will stretch for miles up the East Side, perhaps even restoring a glimpse of the natural landscape, and habitat, that graced the island once upon a time.