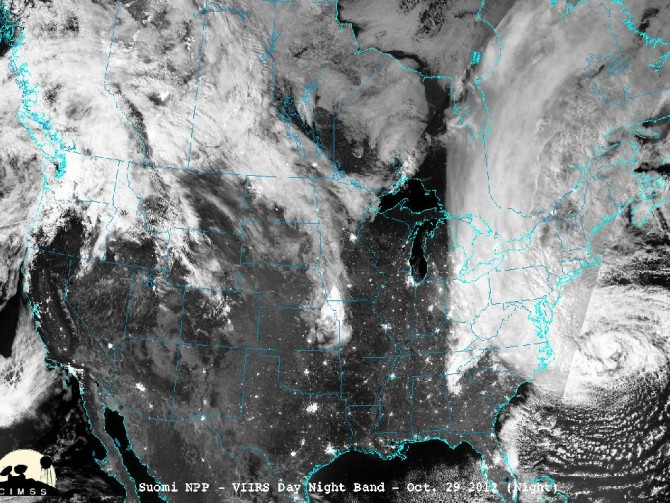

The wind, rain, and debris from Hurricane Sandy caused an estimated $20 billion or more in damage throughout the metropolitan area of New York and parts of New Jersey. A messy wake-up call for millions of Americans, and a tragedy for some, Sandy’s aftermath is now forcing professionals, politicians, and the public alike to confront the science. New York City is a “concrete canyon that is continuously torn down and built up” (Frances Rosenfeld), but in an age of rising tides it is vulnerable as it is strong against the surrounding waters.

“The Science Behind Superstorm Sandy,” a moderated panel discussion at The Museum of the City of New York led by NY1 anchor and seasoned environmental reporter Elizabeth Kaledin, provided a framework for a discussion of the city’s future. Kaledin asserted that “covering weather will no longer be about how it disrupts our local lives but how it affects us in the bigger picture — how we live and how we prepare for the future.”

One of the panelists, Columbia Professor of Climate and Atmospheric Science Adam Sobel, stated that Sandy’s surge was the highest ever recorded by a tide gauge since 1920, and its size (the area affected by the tidal surge) was the biggest since recorded dates have been available.

Was Sandy caused by climate change? According to Professor Sobel, it is the wrong question to ask. Instead we should ask, do we expect more disasters like this? The science says yes, and not only will they get worse but they will also become more frequent. According to William Solecki, Director of CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities, we could start seeing a 100-year flood every 1.2- 3.4 years by 2080.

In terms of defining the science behind Sandy it is complicated to relate any specific event to climate change, but the manifestations of climate change like sea level rise will make storms stronger on average, decreasing the resilience of New York City and other urban areas vulnerable to sea storms.

There is an all-time high awareness on the subject now, across the public, business and government, but public attention has a limited shelf life between events. When everything goes back to normal, people forget. But with 127 miles of coastline facing a rising open ocean, it’s about time we began to think about how to waterproof New York.

This call to action carries several challenges, but panelists alluded to some possible solutions. Finding critical points in urban infrastructure to make changes, for example retaining walls higher than the 11-foot ConEd structure, is one step forward.

How would engineers, scientists, and city officials to prioritize which infrastructure elements need the most attention? One panelist, Cliff McMillan, suggested the need for a methodology to decide what is the most vulnerable.

Another suggested approach is an interface between science and engineering– an attempt to show achievements and progress and to get the business elite and economists on board with efforts.

Every panelist agreed that Sandy will not, despite their hopes, be a turning point in public opinion on climate change. The fact that waterfront developments and Hudson Yards projects have gone along as previously planned could be seen as examples of this.

The panel ended on a note about flexibility. Several panelists commented on the need for the city’s existing infrastructure to be retrofitted, and for new infrastructure to be adaptable for future rising currents. Despite the start-and-stop nature of adaptation (which will perhaps accelerate after a comprehensive report from the mayor’s office is released in May), panels like this one show the city beginning to intellectually grasp the shape of the future and how to respond.

Images: NASA