Looking to entertain out of town friends or relatives this holiday season? Take advantage of the opportunity to act like a tourist in your own town and sign up for a walking tour with the Municipal Arts Society. The weekly Grand Central Terminal walking tour (every Wed, 12:30 – 2 pm), led by New York native Marty Shaw of ManhattanWalks , offers unique and entertaining insights into one of the city’s historical sights. It’s free and worth the time.

Longtime New Yorkers will remember that Grand Central was not always as “grand” as it is today. Like many sites of mass transportation, it struggled with the rise of automobiles after World War II. Budget cuts to stave off bankruptcy included eliminating all maintenance costs except for a once per week sweeping. When the Terminal was restored in 1990s, the ceiling was covered in dirt, entirely obscuring the paintings we see today. When it was finally cleaned, an analysis of the ceiling grime revealed an 80 percent nicotine content, a remnant of bygone days when people smoked inside the terminal. Today, a square of soot remains preserved in the southwest corner of the ceiling. It is visible from the ground if you follow one of the gold bands all the way to corner above Track 30.

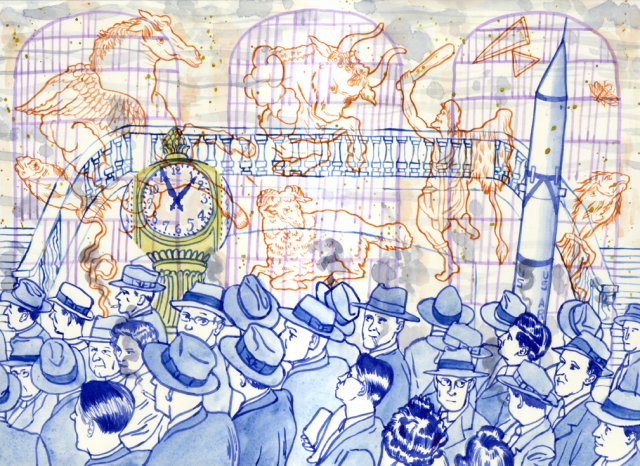

Historic traces persist throughout the building, if you know where to look. On the opposite side of the ceiling, there is a small hole visible just north of the east staircase. In 1957, during the Sputnik era, President Eisenhower sought to display military might. The federal government distributed Redstone rockets to be publically displayed in squares and centers throughout the country. The rocket made for Grand Central was sent out in pieces and, when assembled, measured 127 feet. The terminal ceiling, however, measured 125 feet. To accommodate the rocket, by anecdote, a hole was cut in the ceiling. According to Marty, they used to cover the hole with a “shmear of blue paint and plaster” but decided it was a good story and today it remains unobstructed.

[Ed. note — it does not appear that the rocket would have been tall enough to reach the ceiling. But it is a reminder that during the Cold War New Yorkers understood themselves to be on the front line. The Kodak billboard on the left, occupying the space where the Apple store is now, says “The camera records our power for peace.”]

The preservation efforts of the 1990s reflected decades of fighting to maintain the monument. In 1954, proposals by the New York Central Railroad included tearing down the Terminal, leading to a lawsuit. In 1975, the Supreme Court struck down the Terminal’s landmark status and preservationist mobilized quickly to save building. Jaclyn Kennedy Onassis saw an article in the New York Times and lent her support to the preservation commission, of which she was named president on the spot. Their efforts were successful and are often sited as the first major victory for historic preservation in NYC. Today, a plaque in Vanderbilt hall commemorates their efforts.

In addition to its significance as a historical landmark and example of the Beaux-Arts style (a neoclassical architecture style), Grand Central Terminal marks important moments in transportation history and the impact of transportation on the way we design cities and buildings. In 1902, a fatal accident between two locomotives occurred because of the lack of lighting and ventilation, and the pollution caused by steam locomotives then in use. Municipal authorities gave the railroad until 1910 to get rid of steam locomotives.

Head engineer William J. Wilgus then spearheaded the necessary technological innovations, including the electric locomotive and turbine. The changes required financing and Wilgus came up with another groundbreaking innovation, this time in policy and economics. He proposed renting the air space above the surrounding land. To this day, buildings pay rent to railroad for cubic feet of air space above railroad land, coining the phrase “pulling money from air” and setting a precedent that continues in urban development to this day.

Transportation centers reflect not just design conventions and technological innovations of their time, but also produce and reflect the cultural and socioeconomic contexts from which they emerge. The famous staircases of the Main Concourse tell one such story. Known for the sumptuous use of marble, the Main Concourse features two staircases – the east and west. The west staircase was part of the original building though the east staircase appeared during a later expansion. Besides location, the staircases bear several distinctions. While the east staircase is plain, the west features handrail carvings of oak and acorn. The motif of oak and acorn repeats throughout the building, including on the chandeliers. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the Terminal’s original financier, chose the design as his family crest because it represented the rags to riches tale of a middle class man becoming one of New York’s most powerful and wealthy residents. A less obvious distinction is that the east staircase is one inch narrower than the west. Designers claimed that when archeologists of the future dig up Grand Central Terminal in 1000 years, they will know that the west staircase was the original because it is slightly wider. This prompted Shaw to announce, “tour guides don’t make up stories, you don’t have to, because the truth is so stupid.” A slightly less humorous distinction is that the original staircase was built on the west side because that was the side wealthy travelers would use. At the time, the east side of Manhattan hosted squatters, meatpacking factories, and manufacturers. In other words, not Grand Central’s main customer base.

Transportation centers do so much more than get us from point A to point B– they provide a cross-section of life and serve as commercial, social, and economic centers. From hosting television broadcasts to tennis matches to holiday shopping kiosks, Grand Central Terminal remains a hub of NYC and a vibrant aspect of urban life.

Grand Central Terminal Trivia:

- The famous 125-foot-high ceilings of the Main Concourse–painted by French painter Paul Helleu in 1911–feature a view of the Mediterranean sky as it appears October-March. After the building opened, people realized that the over 2500 starscape was, in fact, backwards. Officials covered the mistake by claiming that it was intentional “so you can see what God sees when he looks down from heaven.”

- The Transportation sculpture outside of the Terminal features Mercury, Minerva, Hercules who cluster around a clock that is the largest piece of Tiffany glass in world. If you look closely, you’ll see that the roman numeral four is wrong, appearing as “IIII” rather than “IV.”

- The Oyster Bar in the Dining Concourse is, according to Shaw, one of the worst places in the world to have an illicit affair. The terracotta tiles, arranged in a herringbone pattern in arches, will carry sound across the room, even if you are whispering.

Images: Illustration: Kurt McRobert, Ceiling: Brooklyn Art Project, Rocket: LIFE, Locomotive: Theme Trains, Staircase: NYC Architecture