Michael Bierut is a partner at the design firm Pentagram. His work is represented in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

[pullquote align=”right”]The public won’t ever tell you, “this is how you change our mind.”[/pullquote]As a designer, how can you learn from the public to meet their needs or redefine the problem? How can we learn from the public and make something that’ll convince them, for instance, of a long term problem like climate change?

Michael Bierut: The public won’t ever tell you, “this is how you change our mind.” People will say, “oh, the general public has an inability to take in information on multiple levels, so the only intake they can handle is coarse, low nuance, low density bits of things.”

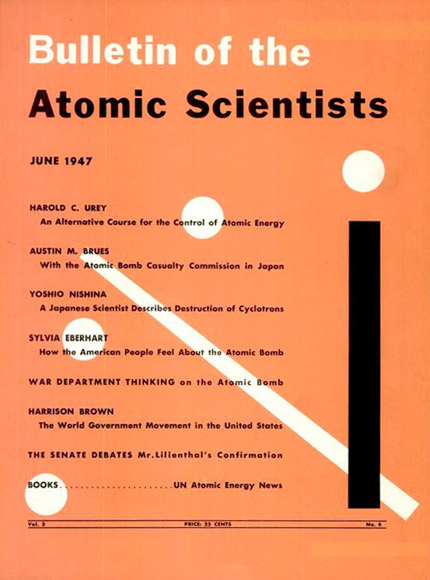

On the other hand, a compelling explanation of something can carry the day and have an effect. For instance, by weird chain of circumstance I happen to be on the advisory board for something called the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Now, most people have never heard of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, but most people have heard of this thing that they invented a long, long time ago called the “doomsday clock.”

These were all former Manhattan Project physicists who decided, after they invented the atom bomb, that they needed to take responsibility about how atomic power and atomic weapons would be used, controlled, and, in many of their views, eliminated. Once they invented this thing they were very ambivalent about, they realized it was extremely dangerous.

These were all former Manhattan Project physicists who decided, after they invented the atom bomb, that they needed to take responsibility about how atomic power and atomic weapons would be used, controlled, and, in many of their views, eliminated. Once they invented this thing they were very ambivalent about, they realized it was extremely dangerous.

They were founded in the late ‘40s and they still are active today. Early on, they had a magazine that was called the Bulletin. One of them was married to an artist named Martyl, and Martyl was asked to do a cover illustration for it and just decided to just to show the last fifteen minutes of the hour face of the clock approaching seven minutes to midnight. And she said she put it at seven minutes because she thought it looked cool.

These Ph.D. physicists — who are much smarter than me and a lot of other people — were evaluating whether the world was a more dangerous place to be. And finally one of them said, “well what if we move the hands of the clock and change the position of it depending on our scientific assessment” of whether the world was moving closer or farther away to nuclear annihilation.

Way back in the forties they started this process, and now with some regularity, they have these scheduled meetings where they meet to assess things and decide if they’ll move the clock forwards or backwards.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis it was two minutes to midnight — the closest it’s ever been. The farthest it’s been from midnight was in the ‘90s, during the Clinton administration after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The last meeting they had was in February, and they moved it one minute closer to midnight. They moved it from six minutes to midnight to five.

It’s a really complicated history. There are lots of competing views about it, but the fact is that they’ve agreed this unbelievably simple, almost childish, comic book-y metaphor is meaningful enough to signal the sum of all of these individual scientific political assessments they’ve been making. I think it’s miraculous. It’s really incredible. Martyl managed to intuitively come up with this really simple metaphor that is able to contain multitudes of detail, or be the leading edge, the headline.

And it also ties into any Bruce Willis movie you ever saw – the ticking clock, the hands moving closer, the thing that’s going to happen at midnight. There’s something – it’s Cinderella, it’s a disaster movie — it’s just such a great metaphor: poignant and accessible to people.

And to me, that’s graphic design. That’s really pure graphic design: taking a set of complicated interlocking concepts and translating them into a simple, fairly two-dimensional graphic design idea. That actually translates also into words.

And now, because of communications technology, it’s interesting to try to figure out what actually becomes the most likely carrier of such simplicity. The Occupy Wall Street movement, for example. Every time I’ve heard the creation story of that – attributed to Kalle Lasn, the editor of Adbusters magazine – he says that they had this idea to do this poster that shows ballerinas standing on top of the Wall Street bull statue down on Wall Street, underneath it says “Occupy Wall Street,” and then it says “we have one demand.” Have you ever seen that poster?

[pullquote align=”left”]Both the doomsday clock and Occupy were very organic and they weren’t necessarily conceived to be the thing that they turned into.[/pullquote]No, I’ve never seen that Occupy Poster.

Michael Bierut: No! Exactly! Both the doomsday clock and Occupy were very organic and they weren’t necessarily conceived to be the thing that they turned into. With that cover design for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the scientists didn’t sit down with her and give her a Powerpoint presentation explaining what the survey results said and what their goals were. They didn’t say, “We need you right now to come up with a device that will be an immediately understood metaphor for the dangers of manmade threats to the world in the form of nuclear annihilation or others.” They just said, “Can you come up with some way to decorate the cover of this thing? It looks boring and probably we just got a little donation, so we can afford to print it on shiny paper in a second color. Could we have a picture for the front?”

She actually had some advice, I learned, from the graphic design director at the Container Corporation of America – this guy named Egbert Jacobson – who told her to project a vague, very metaphoric and indirect sense of foreboding. “Clock is ticking.” But it didn’t mean anything specific.

Then he said, why don’t you just do this every time except keep the art the same and just change the color? And that was a proto-modernist approach – so they did that. They got repetition on their side and then a little bit later had the inspiration to take this thing that they’d been putting out there and decide that it meant something.

So how does this relate to design happening around political movements now?

Michael Bierut: Adbusters does all kinds of stuff all the time. They’re always buying. They’re trying to create these big global movements and then they did this thing that started with this poster that few people have seen, and those few who’ve seen or heard about it don’t quite get it, but it actually had those words “occupy wall street.”

And eventually it got tweeted out with a date and that tapped into a movement that was already somehow happening, and that gave the image a focus. So all of those things are guerilla movements in way. They’re leaderless, they don’t necessarily have believably clear goals at the beginning, and they grow in an organic sort of way. I think part of the problem is that we live in a time that’s built perfectly to accommodate guerilla movements and the world still has tons of Napoleons.

Napoleon thought the way a proper battle gets fought is you get everyone in uniform matched up perfectly, then you line them all up row after row after row after row. You’re all waiting on the top of the hill, the sun starts to come up, and at dawn the battle begins and they all march in the row against other guys marching in a row, and they just shoot at each other. Eventually the battle’s over and a lot of people are dead and maybe the battle line has moved, you know, a mile one way or twenty feet the other way.

Apple is Napoleonic in the way they administer their brand. It’s not like that doesn’t work; it can change hearts and minds even if the goal is to make everyone convinced that there’s one best kind of phone to buy. You can make it work in the command and control way. But even Apple has depended a lot on the ability of independent people developing apps for them. Their sort of centralized control model isn’t really the whole story with them.

Guerillas just sneak up and think, “lets go around behind that tree and shoot that thing.” It’s much more opportunistic, it’s much more incremental, it’s much more insidious, much more relentless. I think good incrementalism and relentlessness and insidiousness – ubiquity, let’s say – are all traits that could serve communications really well.

Cities are where it’s always worked best just because people live in close proximity to each other — plugged into networks that were there just to make the city work. Now those networks are all mirrored digitally, so people can feel that they’re parts of communities even if they’re really living in disparate places. So there’s a whole interesting conversation you can have there from the communications point of view too.

What interests you about City Atlas?

Michael Bierut: One of the reasons City Atlas is interesting to me is that I think that New York is a working model of a sustainable community, and because density and efficiency has a lot of lessons for the future. Every city is different and every community is different — every place has its own set of conditions that have formed it and particular influential people within it or just sort of everyday people that affect its future. But I think New York is really special in that regard.

I grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio in a traditional suburban cul-de-sac development that was built in the ‘60s, with all its shortcomings, with the ride across the superblocks to the nearest shopping mall, that was brand new when we moved there.

It sort of went through its life cycle of aging and quasi-renewal. We saw the whole thing. And at large, we saw all the problems with suburban life and sprawl and everything.

I think it’s good, the sort of the density, efficiency of the kinds of interactions we can have here in New York. And public transportation – all those things, and so I moved here immediately after I graduated from college.

As much as designers are flattered to think that they are equipped to have special insights into the world, I don’t think that they’re that much more equipped than dentists are to tell you the truth – quote me on that – but I do think that I really, I personally just have a passion for New York – not an absolute monogamist sort of passion – I live in Tarrytown, in Westchester. I live back in the suburbs now.

Do you drive?

Michael Bierut: Once every three months. I get in cars every once in a while, but I live 90 seconds from Metro North. When [my wife and I] moved, and this was a long time ago, we sort of determined we needed to be close to Grand Central as opposed to Penn Station, just because of my admiration for Grand Central. And then I take the bus to work every morning. I walk over to the bus stop.

I don’t know many people my age who ride the bus. There’s one designer who’s lived here since the ‘70s and claims he’s never been on a bus.

On a trip in 1974 we took to New York in high school, we were given a mini hand-out of tips about New York, and one of them was ways to get around the city, and they listed walking — ‘most interesting,’ subway – ‘fastest,’ and then there were buses – ‘see the most.’

And I still remember that really clearly.

And so, speaking of the MTA and Metro North, the big break through in my life was when my Metro North pass started being paired with a metro card – an unlimited metro card. Now I will walk out of a meeting at the Museum of the City of New York and if there is a number 2 bus going by, I’ll just think “oh, free ride!” A free ride in this giant chariot — and it’s fantastic.

About

Michael Bierut studied graphic design at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning. Prior to joining the international design consultancy Pentagram as a partner in 1990, he was vice president of graphic design at Vignelli Associates. His work is represented in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Montreal. He has served as president of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) and as a director of the Architectural League of New York, and is a member of the Art Directors Club Hall of Fame. He is a co-editor of the Looking Closer series of design criticism anthologies and a founding contributor to the online journal DesignObserver.com, and the author of Seventy-Nine Short Essays on Design (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007). In 2008 he received the Design Mind award from the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, and he is currently a senior critic in graphic design at the Yale School of Art. Michael Bierut’s father served in the U.S. Army during the occupation of Japan, and was stationed in the city of Nagasaki.

Top photo: Maureen Drennan

Inset image: Design Observer

_