Robert Moses, Fiorello LaGuardia, and Franklin Roosevelt are well recognized in New York City for their accomplishments. Moses has a state park, LaGuardia an airport, and Roosevelt a Drive, an island, and a recently unveiled memorial.

Andrew Haswell Green, whose contributions to New York City are no less extensive or remarkable, seems to have been lost amid the obscurity of a forgotten history.

Professor Ken Jackson of Columbia, editor of the Encyclopedia of New York City, calls Andrew H. Green “arguably the most important leader in Gotham’s long history.” Green was a key figure in the creation of Central Park: he led the State Commission charged with building Central Park, and managed to secure the adoption of the Greensward plan (Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s plan for Central Park).

Central Park was just one of Green’s many accomplishments. He also founded the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the New York Public Library, and the Bronx Zoo, creating the outline of New York’s cultural landscape. He added Riverside, Morningside, and Fort Washington Parks to the map. In 1871, Green was appointed to the position of City Comptroller, where he played a significant role in relieving the city of the “Tweed Ring” – the corrupt group, led by William Tweed, that controlled and bankrupted the city’s treasury. Green was able to restore the city’s financial health following the crisis, and he saved City Hall from demolition.

Most importantly, Green successfully lobbied for the consolidation of the five boroughs. In 1898, New York was consolidated into one city, earning Green the nickname the “Father of greater New York.” The consolidation of the five boroughs encouraged the construction of the subway, which in turn spurred the growth of the outer boroughs.

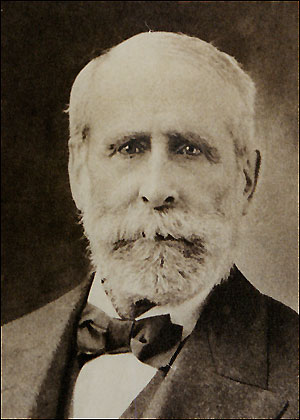

Despite Green’s rich legacy, the only visible remnant of his handprint on the city is a stone bench in Central Park. A portrait of Green also hangs in City Hall, but it’s in an area closed off to the public.

Michael Miscione, Manhattan’s borough historian, has long fought to garner greater recognition f0r Green, whom he calls “a forgotten visionary.” In 2003, Miscione proposed two name changes to honor Green. The first was to rename Washington Bridge, a little-known bridge spanning the Harlem River, connecting Manhattan to the Bronx. (The bridge was actually conceived by Green.) The other proposal was to rename the Tweed Courthouse (now home to the Department of Education).

A Park for Andrew H. Green: Tribute at Risk

Several years ago, the Department of Parks and Recreation agreed to build a park in memory of Andrew H. Green. The 1.3-acre waterfront park would be located on a tiny sliver of land between F.D.R. Drive and the East River, from 60th to 63rd Streets. The City Council approved the project in 2006, and the first construction phase of the park broke ground in 2008. The first phase of the park is complete, and features a dog run, drinking fountain, chess tables, and plantings, including trees and shrubs.

The park was scheduled to be completed by 2012, but progress has been halted due to unforeseen circumstances. Last June, the Parks Department began an engineering study for the second phase of the park and discovered that the pilings supporting the park were slowly being eaten away by marine borers – underwater organisms that feed on wood. Now, the Parks Department says that $15 million is needed for repairs. Otherwise Andrew H. Green Park risks falling into the East River.

Andrew H. Green park is one piece of the larger East Midtown Waterfront Project, which would provide waterfront access along the East River, between East 38th and 60th Streets. The East Midtown Waterfront Project is one of several planned projects for the East Side Waterfront. The NY Times created a comprehensive map of the projects currently in progress. When all of the projects are complete, there will be a nearly continuous greenway running along the East Side, south all the way to Battery Park. If Andrew H. Green Park fails, the link in the greenway would be broken.

Explore the East River Blueway Plan on City Atlas to learn more about the plans for the East Side Waterfront.