ALICE LARKIN, HEAD OF SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER:

There are things that we can do as individual citizens. We can make choices about our lifestyles and the things that we buy and the things that we do and how we travel and so on. And then sometimes people will criticize and say well you’re only a tiny little part of emissions and why does that really matter?

And I think that’s where it links up with how you might understand the world through the eyes of the social scientists, where actually what I do might affect you tomorrow, or, you might forget all about this. And what you say to me tonight might affect me as well. So we’re not individuals in that we operate completely in a silo. We interact with each other, we talk to each other about issues and we have influence on each other.

GABRIEL GITTER-DENTZ:

Thank you for tuning in. My name is Gabriel Gitter-Dentz. I’m a senior at Hunter College High School and I live in Manhattan.

ADAM RUDT:

My name is Adam Rudt, I’m also a senior at Hunter College High School, and I live three blocks away from Gabriel.

KEVIN ZHOU:

My name is Kevin Zhou and I’m also a senior at Hunter College High School, and I live in Queens.

ADAM RUDT:

So welcome back to another episode. High school students don’t normally talk about climate change in their own school. Our aim in producing this podcast is to form a conversation about climate change among family and friends, specifically between young people who are the future of climate.

KEVIN ZHOU:

On today’s episode we would like to welcome Dr. Alice Larkin. Can you introduce yourself?

ALICE LARKIN:

Hi yes hi my name is Alice Larkin. I’m a professor of climate science and energy policy at the University of Manchester in England in the United Kingdom. And I’m also part of the the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research. I’ve been a researcher there since 2003.

And then my main day job at the moment is Head of School of Engineering at the University of Manchester.

ADAM RUDT:

So we’re super excited to have you. We’ve done a good amount of looking at some of your talks online and I think, Richard, our handler, said that if there’s anyone to talk to right now the best person in the world to talk to is you.

KEVIN ZHOU:

Today we’ll just be talking about a variety of topics, including Dr Larkin’s research including her work on aviation and shipping, the energy, food, and water nexus, and emission budgets. So just to start off with a basic question, what are you currently working on?

ALICE LARKIN:

Well, I have limited time on research at the moment, but the area that there are two researchers that I’m working with on shipping, which is kind of exciting at the moment so one of the PhD researchers is looking at wind propulsion for shipping, which sounds a little weird because, in a way because it feels like you’re going backwards and then it’s actually kind of high tech wind propulsion to decarbonize the shipping sector. And the other PhD researchers are also looking at shipping and looking at whether there’s an opportunity for shore power for ships. When ships come into port, they need to stick around for quite a long time and they use quite a lot of energy, just while they’re in port. Are there options for basically plugging in — it’s called cold ironing. And if they plug in, could they be plugged into renewable energy while they’re there?

One of the nice pieces of work that this person has also done that we’ve worked on as a nice paper was actually looking at some of the timeframes for achieving things like the Paris Climate Agreement, so, how quickly you need to reduce emissions by. What does that mean for a sector like shipping, which is one of those sectors that not a lot of people don’t think about? I mean of course, the UK is an island so you’d think we think about it a lot, but you know it’s not really in the consciousness, like aviation is very much in our public consciousness. But you know if the shipping sector had to meet the Paris Climate Agreement, and they had to change as much as other sectors, what’s it need to do? One of the things that we found is that actually a lot of times we think about new technologies and new stuff that can happen in 20 or 30 years time, but because ships last a really long time, basically the ships that we have now, we need to work out how to retrofit them and decarbonize them. Now we can’t just rely on building new ships and new technologies. And we can’t also just rely on new zero carbon fuels because that’s going to take a long time.

So one of my main areas that I’ve focused on for years is the timeframe to change, to make the changes, and how that needs to be really rapid. And that changes what you might do. You can’t just rely on huge infrastructure projects because they take ages to come to fruition.

ADAM RUDT:

How bad are ships, compared to planes?

ALICE LARKIN:

Well, it’s really difficult to make kind of direct comparison as I guess you could imagine, because measuring the carbon per person for a plane compared to a ship, you’re not moving around passengers in the same way. You’re using air travel for largely for passenger transport and freight. And actually, in terms of how efficient ships are, they’re very energy efficient, they’re pretty carbon efficient as well. The challenge is that they go a really long way, there’s a lot of them, and they’re really big.

So when you think about the different kinds of activities that we do in terms of carbon intensity, aviation is going to come out on top. The carbon intensity of your flying, as an individual, kind of the worst thing you can do is to take a long flight.

Shipping is a lot more complicated than that because you’re transporting a lot of freight around. The difficulty is that these, it’s like any sector where the technology or the infrastructure lasts a long time. That’s where we have this problem. So you mentioned that if you have a car and you tend to change it, maybe you might have a new car, you might upgrade it in five years or 10 years or something. And typically you won’t have that car sticking around for more than 10 years or so. And if you’ve got a ship, then that is going to last a lot longer than that. And the same for planes, they lost an awfully long time. I often get grouped together, aviation and shipping, partly because they last a long time but one of the main reasons is because they operate internationally, which is kind of an obvious thing to say but it means that if you’re if you’re a policymaker in a particular country like the UK and you want to do something about aviation, then on the Kyoto Protocol and on the Paris Climate Agreement, you’re only responsible for the domestic aviation and your inland shipping. Whereas, you know clearly a flight between Manchester and New York, you know in some ways you need to share it out between those two places. But actually what happens is, they’re governed by international agreements. That applies to shipping and aviation, so they’re so they’re similar in that way, but then they’re different in pretty much every other way I would say.

GABRIEL GITTER-DENTZ:

At the end there, you mentioned that different countries have to collaborate in order to make an agreement on aviation. Would you say this has happened successfully? Have there been recent agreements that have been effective?

ALICE LARKIN:

There hasn’t really been a great deal of multilateral agreement on aviation, other than it’s governed by the International Civil Aviation Organization. So they were asked, this is an international organization, and they were given the mandate by the United Nations to deal with international aviation. So rather than, say, the United States and the United Kingdom having some sort of agreements do something about international aviation, that hasn’t happened, we haven’t got those agreements between countries. And instead, the International Civil Aviation Organization has not really put in place the kind of measures that we would need to decarbonize aviation in line with something like the Paris Climate Agreement.

They’ve said that they would put together policies. So one of the latest things that they do is called CORSIA, which is like a carbon offsetting scheme. So, they would prefer countries not to actually do something about aviation individually, they’d rather manage it themselves.

But the measures that they then agree with the industry players, have either been , to date, voluntary. And they have also been things like offsetting. They’re keen to to work on energy efficiency of course and support energy efficiency measures but that makes sense anyway because you know one of the big costs for any airline is fuel. So if you can reduce the amount of fuel you need anyway, then it’s going to cost you less. Energy efficiency has always been a big driver. So, I would say that they haven’t, for years, they haven’t done anywhere near enough to address the problem of aviation emissions.

And still now. even getting different groups together to try to get some sort of agreement what should be done, the carbon offsetting scheme, and these other things, are not going to get down the track of really decarbonizing the sector, like all the other sectors need to do. So it’s really pretty weak. what’s in place to tackle aviation.

ADAM RUDT:

I know 2050 is a big target here. So what are some things that need to be done by 2050?

ALICE LARKIN:

Well, I would kind of push back on the 2050 thing a little bit. One of the things I would just say is that we focus a lot on these long term targets, and what that gives some people the impression of, if they don’t understand the concept of greenhouse gas emissions and how they build up in the atmosphere, then it sounds like as long as we get the technology right by say 2045 or something, and then we put it in place, we’ll be ok.

And that’s not the issue. The issue is that the emissions accumulate over time. So it really matters what you do now, as well as by 2050. Where you’re starting now, you need to bring emissions down. Which kind of sounds like an obvious point but it isn’t always understood in that way.

There’s a big issue around equity and justice in this whole climate debate, The wealthier countries where our per capita emissions are really high have got an awful lot more work to do than poorer countries, and in the poorer countries development still needs to happen and that might have to rely on on fossil fuels. So if you take that view, so actually there are differences between the different countries in terms of what we need to do. A country like the UK, and the United States, we need to be cutting our emissions from our energy systems — that’s from all the supply side of energy, looking at energy efficiency across our whole system — down to zero by about 2040, I would say.

And that’s a huge ask. That’s a huge ask particularly for sectors that are quite difficult to decarbonize like aviation and shipping. But part of the reason why you need that from your energy system is because you’re still going to have greenhouse gas emissions from the food system as well, that are going to remain in the atmosphere. And they some of those are even harder to reduce.

Clearly we all need to eat. Around the world population is growing, people are eating better, and that’s a good thing. But the point is that even organic practice you’re still going to be producing nitrous oxide, which is going to be a greenhouse gas, and so there’s a certain amount of emissions we’re going to have to leave in the atmosphere. And that means you’ve got to do more on the sectors that you can reduce emissions from, so that might be car transport and so on.

GABRIEL GITTER-DENTZ:

In terms of how this reduction is actually going to happen, in your quote in a New York Times article, you said, “In my idea, people move first.” Rather than governments. So what do you think is the role of people in terms of culture that needs to be changed?

ALICE LARKIN:

That’s a really good question. And I think it’s quite difficult to be correct about it. I mean, I’ve learned an awful lot from my colleagues who are social scientists and I’m not a social scientist myself. And what it seems to me to be, there are a number of different things.

There are things that we can do as individual citizens. We can make choices about our lifestyles and the things that we buy and the things that we do and how we travel and so on. And then sometimes people will criticize and say well you’re only a tiny little part of emissions and why does that really matter?

And I think that’s where it links up with how you might understand the world through the eyes of the social scientists, where actually what I do might affect you tomorrow, or, you might forget all about this. And what you say to me tonight might affect me as well. So we’re not individuals in that we operate completely in a silo. We interact with each other, we talk to each other about issues and we have influence on each other.

And clearly like things like the climate movement, they start and they they build because people talk to each other and they discuss the issues and not of course not everybody will agree on everything that needs to be done, but you share your learning. And different people will be interested in different parts of that and you share that.

I think there’s also a really important role for us to play in whatever realm we’re in. We have some sort of influence and I’m very fortunate to be in a position now where within the School of Engineering I get to sit on committees that talk about deciding who we’re going to employ or what research we might invest in and so on. And I can have some sort of influence to to push that towards an important energy agenda, or looking at the environment, and so on, and that’s a big influence I have.

The whole time that I’ve worked in this, and before, when I was studying and so on, I still had influence. Because you might influence your supervisor, or you might be on a committee, like a student committee or something, and you get some choices or a get a budget to do something with. And you can also — I don’t know how your system works in the US but here we can write to our members of parliament. And that actually has quite a big kind of impact if they’re getting the same message from lots of different people and they’re saying, you know, we think onshore wind turbines are a really good idea, and we really wish you would push forward and be more bold. And then they can take more difficult decisions.

But if we just sit back and we sort of give the impression that we’re not very interested, then I think that the politicians and the people who have to make difficult decisions and invest money in the right places, they don’t know whether we’re behind them or not, and they don’t know whether we’ll vote for them again if they come up for election. So they might not make those difficult decisions.

And it is difficult. It’s not like it’s not like what we need to do to meet the Paris Climate Agreement is all easy and it’s all nice new sort of sparkly infrastructure and technology. And so it’s tough. And so we need our politicians to make difficult decisions so I think that we have an influence, we have an opportunity to influence it. And you just do it in different ways, all the way through your life. And you just need to take opportunities.

ADAM RUDT:

It definitely sounds really difficult to be active. Everyone can be a climate activist, but it’s really, really difficult. How do you suggest getting people to take ownership, how do you get people to write letters, to feel some sort of attachment to the issue, when it seems so far off or it seems like there’s gonna be one solution that’s going to come into play later and save us all, which is not true.

ALICE LARKIN:

Again, I think if we knew that, if we knew the answer to that, then I guess we wouldn’t be in the situation we’re in. I was hoping you might be able to help with that.

ADAM RUDT:

How do you, what approach do you take when you try to talk to people, like a normal person on the street?

ALICE LARKIN:

Yeah, and I don’t know, I mean I’ve gone through kind of like waves of different things actually because at first when I first joined the Tyndall Centre, I was really excited by the energy that was there and people talking to each other about climate change and about what they did in their lives and so on, people spoke a lot.

And then when I found when I spoke with my family or friends who are just not, it’s just not in their world. And I would actually sometimes find that quite difficult. And so then I sort of stopped talking to immediate friends or family because you don’t necessarily want to get into arguments with people about stuff.

And then I found that people would want to talk to me about it when I didn’t really want to talk about it. So one of the things that used to happen to me, particularly when I worked on aviation, was people wanted to, almost like, confess their flights to me. So like they’d say, hey, Alice, ah, you’re going to be really cross with me because I took a flight to Costa Rica. And I’m like, you know why why are you telling me? I can’t do anything about it. And what you don’t want to do is you don’t, I mean this is just my personal view, I would rather not not make somebody angry about it. I’d rather try to understand okay well, why did you do that? Are there other other things that you might do next year that might be different?

Just trying get people maybe just reflect a little bit, but without being antagonistic. Particularly with people who haven’t really thought about it before, because there’s an awful lot of people in the world who just do not think about climate change, whereas it’s my whole world. So, you know you have to be really careful not to to really put people off when you’re talking to people. And also I think people don’t, I mean, other people would argue with me about this, but I don’t think people like to feel guilty about things if they’ve never thought about it. I think the first stage is just to start thinking about it. And maybe build a bit of an awareness of, well, flying is much worse than driving an electric car or just making some comparisons for people even if that’s just a little starting step.

Because the other thing that you find over the years is you get asked to do talks but very often the people you’re talking to, they’re already interested in climate change, if that makes sense. And actually, the much more difficult meetings would be if I went to an aviation industry meeting or shipping industry meeting talking about climate change. And in that kind of audience I think you just need to be really direct and stick to the science and just say that this is a really big problem. This is why it’s a bad thing at the moment, and we need to move forward. So I’m just trying to show a pathway out of it rather than just focusing on the problem. I think you have to provide people with solutions.

ADAM RUDT:

When talking to people have you ever come across a client or someone who just like outright doesn’t believe in climate change?

ALICE LARKIN:

Yeah. But must be a very long time ago actually now. I mean there were many more people previously. When I started working on climate in 2003, I would say there were a lot more climate deniers around in the UK then. But you don’t come across that very often now. What you’re more likely to come across in the UK at least, and I obviously can’t speak for everywhere else, are people who do understand that climate change is a problem, who also understand that it’s a human created problem, but they think that the solutions are just that we don’t need to actually reduce energy consumption and we don’t need to decarbonize things, we’ll just be able to deal with the impacts, and just deal with the consequences. So I think you come across that more now than the kind of denier I would say in the UK. It’s quite unusual now to come across climate deniers. I don’t know what it’s like in the United States. It’s not very common now in the UK.

GABRIEL:

So — what you said about preparing for the impacts of climate change, and I know you mentioned before how different wealthier countries are more responsible for the problems. I assume there would be a big disparity in the ability to defend against the effects of climate change. How does this come into play?

ALICE LARKIN:

Yeah, I mean, unfortunately the places that are kind of responsible for most of the cause of the climate change impacts that we see now are also the places that can deal with the problem. They have the money, the infrastructure to deal with it within their own countries. But the places that are really impacted are those places that just don’t have the infrastructure and don’t have the money. And often they have some of the more extreme weather events. Although I’m saying that and I’m thinking about the United States, and I guess you have much more extreme weather events than we do in the United Kingdom where our weather is kind of, it’s not very exciting. Whereas you have these more extreme storms and so on, and that’s certainly something that, we’re seeing stronger impacts of those kinds of storms. But then, when they hit in a wealthier country, generally there will be fewer deaths, there will be more rapid infrastructure improvement, and there will be insurance, that kind of thing.

When they hit a poor country, you know a lot more people will lose their lives but you may well have your whole livelihood devastated forever. Now that’s not to say that there are people who would be impacted like that in wealthier countries because clearly, you know, Hurricane Katrina was an example of that where there were many people who were really terribly affected. But again, they would typically be the poorer end of society that were really badly affected. You know this issue of wealth, it’s really clear in climate change, that the wealthy produce the emissions and the poor suffer the consequences. There is that quite big divide. Which means that it seems to become quite political, because then you know the kind of ways in which you might address that we’ll talk about it, then appears to be coming from a particular point of view, when actually all it is is just identifying that, you know, emissions come from high energy use, and therefore from wealthier parts of society, and then clearly like you saying that if you’ve not got the infrastructure, if you’ve not got money to spend on protecting people with flood defenses, and that kind of thing, then clearly those people are going to be the ones suffering the consequences.

And the range of impacts is very great, of course, so it’s not just about storms and extreme weather, but you’ve got your droughts, and wildfires, which I guess for you guys, that’s been something that is, been a lot in the media, I understand has been difficult this year. And you know that’s not something that we typically get in the United Kingdom. So different places for different places,

ADAM RUDT:

In our second episode we had Professor Radley Horton from Columbia and he talked about his research on wet bulb temperature. My stab at it would be the air getting to a dangerously humid but also very hot temperature.

So the problem with having high wet bulb temperatures is that it increases probability of heatstroke and other heart conditions. And it also it also brought in a lot of socio economic factors where countries that didn’t have the infrastructure, to just for example have air conditioning, people are much more likely to suffer from the effects of these emissions.

ALICE LARKIN:

Yeah, sure. And you know, It’s also the irony that if, as countries become more wealthy, and then people have the access to things like air conditioning units, but then as temperatures go up you’re using more air conditioning and you’re using more energy which is making it worse again.

It’s really difficult to see how we get out of that kind of loop. And actually design buildings so that they don’t actually require either heating or cooling, get a passive house kind of design. Which also helps with things, and comes back to the issue of poverty again because if you can, you know, have a home where people don’t need to buy the fuel, and that helps with things like fuel poverty, which in the United Kingdom is a really big problem. You know, people don’t. A lot of people don’t have enough money to, to actually heat their homes and if you didn’t have to heat it, then that would be much better.

Lead photo courtesy of Norsepower. The cylinders on the tanker are Flettner rotors, a wind propulsion device that can help decarbonize shipping. How a Flettner rotor works.

Dr. Larkin narrates this short video on aviation and shipping:

Dr. Larkin previously in City Atlas:

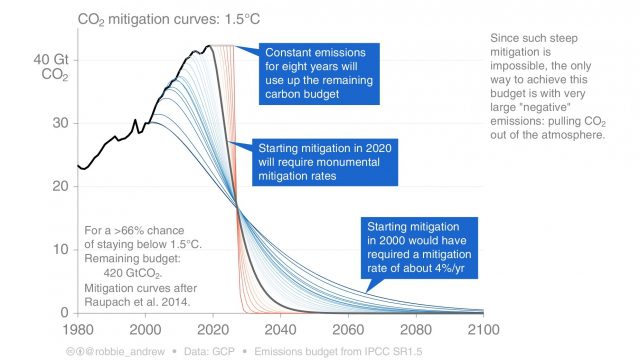

The timeline of emissions reductions for 1.5C:

As quoted in the New York Times, Alice Larkin has not flown since 2008.