Mary Miss is an artist whose work seeks new means of engaging the public in the world around us. In the course of her career she has expanded from temporary site installations to larger scale transformations of infrastructure. She’s currently working on an ambitious project for New York City called “Broadway: 1000 Steps,” that will explain New York’s new green initiatives — many of them part of PlaNYC –at multiple sites along Broadway. The goal is to make New York’s forward progress even more tangible to citizens.

[pullquote align=”right”]Each move in building a building is a decision, and if people can begin to understand those smaller decisions then they are not so overwhelmed by this effort that we have to make to change our lives[/pullquote]

Mary Miss: Broadway: 1000 Steps is a project that I started working on about two years ago. The idea developed through a sequence of encounters. I was invited to the New York Department of City Planning to talk about a larger framework that I’ve been developing over the last few years, called “City as Living Laboratory,” which is about how cities could recognize the role that artists could have in making sustainability tangible.

I’d been working on an earlier project in Indianapolis, where I looked at the corridor of the White River, and tried to get people to take note of the river. Afterwards, when I spoke at City Planning, they were really excited by this approach. Amanda Burden, who is director of of the department, said, “Mary, you should really think of doing something in New York”– and I said to her, “It’s too hard to do anything in New York.”

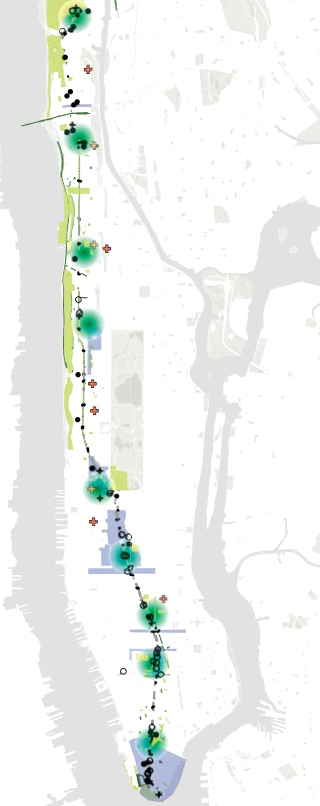

But I was tempted by the idea. So, thinking about it, I felt like looking at a different kind of corridor. It seemed that the corridor of Broadway, the iconic boulevard of New York City would be a really interesting focus.

I started to imagine that corridor as a place to come to see new ideas about the city that artists or designers could implement — whether it was some way of making composting interesting to people, or a new kind of park, or showing where urban farming could happen along the way. Or, if there’s a LEED-certified building, how do people know it’s there? Or if there’s a green roof, how do you know there’s a green roof there?

I thought if artists, over a period of time, could incrementally work on this corridor, people could begin to see the city not just as the home of Wall Street, not just a 19th or 20th century place, but really a city that’s looking to the future. I also thought it would really be an interesting way to get the initiatives of the city’s PlaNYC down at the street level so that people could have access and begin to understand issues that were being talked about between city departments. How do you get the support of citizens?

Mary Miss: Yeah, it goes through all kinds of neighborhoods, it’s the iconic corridor of the city, it’s historically the oldest corridor of the city–it was a Native American trail to start with–it’s the ridgeline through a good deal of the city where the water runs off in opposite directions on either side. Everybody’s heard of Broadway, and every borough in New York City has a Broadway in it. So once we finish with this one we can go to all the boroughs [laughs].

Mary Miss: Our goal is to do it in the spring of 2013. We’d love to have it happen then, but we’re in the process of fundraising and it will depend on how our fundraising goes, so we’ll see what emerges.

Mary Miss: It would probably be over a month’s period of time. We have five primary sites along the corridor and then there would be sub-sites that might be only virtually engaged in some way. We couldn’t do them all at once, but we would move from site to site.

Mary Miss: Yes.

[pullquote align=”left”]This is a way to get the initiatives of the city’s PlaNYC down to the street level, so people can understand them.[/pullquote]Mary Miss: I think that my idea has always been to get this visceral, physical, emotional engagement. A lot of the projects that I did took quite a lot of money to build, they weren’t this kind of acupuncture-like approach. And I think I’m reformulating how I work in the environment. I’d say in the past my projects have always been about trying to engage people with a place and looking at it and understanding it. But as I’ve drilled down over the years doing projects, I’ve wanted to give more information.

For instance, I did a project in Des Moines, Iowa, and it was a demonstration wetland; I made a path around a newly restored pond in Des Moines that street water runoff comes into. We replanted the whole edge to help clean the water, and there was infrastructure being installed to help filter the street runoff; I wanted to allow people to see this demonstration wetland in as many ways as possible. So there was a lookout where you could get up high, and kind of sit and watch the birds; there was a walkway that took you through the middle of some tall grasses; there was a trough, that was a cut in the water so you could sit and look at eye level with the water. I was trying to introduce people to a wetland and how it worked. And I did that and it was finished in 1996, and at that time, I thought, “I’d really like people to know what the plants are that we planted here. I would like them to understand more about the runoff and where it’s coming from and the role of wetlands.” So I was wishing I could add this other layer — and I’ve kind of moved on to trying to get that more specific engagement in recent projects.

Mary Miss: It’s been this huge learning curve for me because I don’t claim to be a scientist, I really take the position that ‘I’m Jane Q. Public, and I don’t know anything about these issues and how can I have them revealed to me in a way that’s compelling.’

And so I’ve had endless conversations. My conversations with Eric Sanderson have really been wonderful. You already know that you’re living on the edge of the Hudson River, and an estuary on the other side on the East River, so you have general ideas of the geography of the city. Eric and I visited a number of sites together, and as we walked this corridor I began to see a more complex geography, to understand at 125th Street what was there, the marsh that formed this inlet. Becoming aware of what it has taken to change this place step-by-step, that has really been interesting. That’s one of the things that I really appreciate.

But also my conversations with Bill Solecki [director of the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities], and his talking about the importance of getting people to understand all the small steps it takes to make a place. Each move in building a building is a decision, and if people can begin to understand those smaller decisions then they are not so overwhelmed by this effort that we have to make to change our lives. I think that’s the hardest things about climate change: people feel helpless, that it’s something beyond their control. And it helps to kind of break things down so that it seems manageable in some way.

Actually the title of the project figures into that — it seems kind of opaque to some people, what kind of 1000 steps are these? Are these dance steps or what? But it came out of a talk that I heard an ecologist give in Indianapolis. She talked about the thousand small steps it takes to degrade an environment, and the thousand steps it can take to bring it back again. So I really liked that idea and I think that’s what I’m trying to do: parse things out in a way that it seems possible to people to participate in this. Because I don’t think there can be change, I really don’t think we can deal with the challenges we face by just relying on the authorities, the G7 or this or that [group of experts] getting together and deciding. I think to get everybody’s actions to shift, we will need citizens’ engagement.

Mary Miss: I think the thing that really interested me was how you could get people who may not ever go into a science museum or an institution, just somebody walking down the street — that people like that could begin to become aware of things like the infrastructure, the habitat, the ecology, the history of the site and how its been shaped. Become aware of events over time.

It would be whoever is walking down the street; it might be tourists, it might be young people, hopefully. But it’s trying to get those who aren’t typically interested in these ideas. I really have this fantasy, this image, that a community could develop that begins to picture New York in a bigger way. I think at this point people don’t really think about water or where it comes from or where it goes after they’ve used it. I would love that to be part of people’s sense of the landscape of the city. Or thinking about the wind patterns, or the geology. That they had a sense that Broadway is a flight corridor for birds. I don’t think anybody ever thinks of that. I would love to imagine that there’s this shared new sense of the landscape of the city, and with that, a greater interest.

Mary Miss: I’m trying to catch them unawares. Someone came up to me and they were very critical. They said “I saw somebody putting lipstick on in your mirrors,” and I thought that was great, that somebody was going to stop, check themselves out, and guess what, they’re going to see something that they hadn’t necessarily intended to see. I did a small test nearby in a local triangle, in a small park in my neighborhood, and I was watching people. And people would go up and start to look at their hair or something. And you would see that double take as they stopped and saw the reflection of the disk with its content. I think to be able to not only see yourself, but to see the city behind you, puts you in the city; it’s kind of drawing you in and making you part of the place just by the presence of the mirror.

Mary Miss: I’m trying to catch them unawares. Someone came up to me and they were very critical. They said “I saw somebody putting lipstick on in your mirrors,” and I thought that was great, that somebody was going to stop, check themselves out, and guess what, they’re going to see something that they hadn’t necessarily intended to see. I did a small test nearby in a local triangle, in a small park in my neighborhood, and I was watching people. And people would go up and start to look at their hair or something. And you would see that double take as they stopped and saw the reflection of the disk with its content. I think to be able to not only see yourself, but to see the city behind you, puts you in the city; it’s kind of drawing you in and making you part of the place just by the presence of the mirror.

[pullquote align=”right”]My idea has always been to get this visceral, physical, emotional engagement. To get people who may not ever go into a science museum to become aware of events over a period of time.[/pullquote]Mary Miss: Well let me describe what’s happening with my earlier project ‘’FLOW: Can You See The River?’ in Indianapolis because I think it’s really interesting. I said when I started out that we were going to do a very modest project, not spectacle, it’s not a big intervention in the landscape. They were very modest, different kinds of mirrors I was using there. But we had about 100 sites in a 6 mile stretch that we were looking at along the river, and what I wanted to feel is that this project could be catalytic, could engage the community so that other things would continue to happen in the future. The project opened in September of 2011.

I was just out in Indianapolis [this summer], and I was invited to come and work with a coalition of about a hundred civic groups, the Lilly pharmaceutical company, and the city. They’re all working together to do a project that makes people more aware of the sub-watersheds that lead to the river. And so in that meeting I said, “What was the role of the project FLOW that I did last year?” and they said, “Well that’s what led to this initiative.” So I was really pleased that it wasn’t just a fantasy on my part, that it was really leading to something else. It was catalytic.

To come back to Broadway, I consider my project to be the initiation of something ongoing. And that people would be engaged at each of the sites. We’re working really hard to contact community groups and different organizations — whether it’s the community board, or a youth market — whoever is around in each particular hub [on the route]. We’re trying to get these groups interested and engaged and we would hope that there would be a way of sustaining an ongoing conversation between them about possibilities of future projects. Is there a possibility to do an urban farm on roofs in your neighborhood? Is there a possibility of doing some other kind of green infrastructure? We’re trying to start a chain reaction on Broadway — one that will turn it into the identifiably ‘green corridor’ where people can go to see the city remaking itself.

To come back to Broadway, I consider my project to be the initiation of something ongoing. And that people would be engaged at each of the sites. We’re working really hard to contact community groups and different organizations — whether it’s the community board, or a youth market — whoever is around in each particular hub [on the route]. We’re trying to get these groups interested and engaged and we would hope that there would be a way of sustaining an ongoing conversation between them about possibilities of future projects. Is there a possibility to do an urban farm on roofs in your neighborhood? Is there a possibility of doing some other kind of green infrastructure? We’re trying to start a chain reaction on Broadway — one that will turn it into the identifiably ‘green corridor’ where people can go to see the city remaking itself.

Mary Miss is a pioneer in the Land Art movement of contemporary sculpture. Over the course of a career spanning from the late ’60s to the present, she has collaborated with architects, urban planners, and ecologists on a broad range of public projects, including South Cove in Battery Park City (completed in 1987), which created the one of the first public access points for the Hudson River; a temporary memorial around the perimeter of Ground Zero; markers for the predicted flood level of Boulder, Colorado, and an installation focused on water resources in China for the Olympic Park in Beijing.

She has been the subject of exhibitions at the Harvard University Art Museum, The Institute of Contemporary Art in London, Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, and the Des Moines Art Center. Exhibitions include: Decoys, Complexes and Triggers at the Sculpture Center in New York, More Than Minimal: Feminism and Abstraction in the 70’s, Brandeis Museum’s Rose Art Museum, and Century City: Art and Culture in the Modern Metropolis at the Tate Modern.

Mary Miss earned her B.A. degree in 1966 from the University of California at Santa Barbara, and her M.F.A. in 1968 from the Rinehart School of Sculpture, Maryland Art Institute.

“Broadway: 1000 Steps” full booklet PDF

See Mary Miss featured elsewhere in City Atlas: “Can art encourage sustainable change?” (6/27/12); “Broadway: 1000 Steps” (2/21/12)

Mary Miss interviewed by the Museum of Modern Art.

Top photo: Maureen Drennan

Inset images: Courtesy of Mary Miss/City As Living Laboratory

_