Terra Nova: The New World After Oil, Cars, and Suburbs by Eric Sanderson

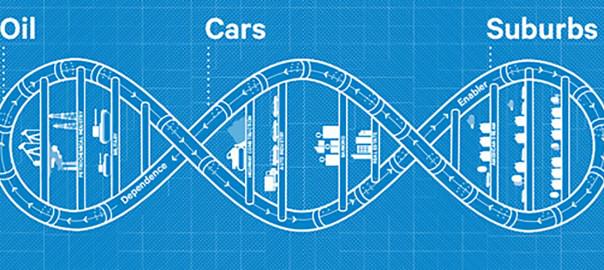

Oil, cars, and suburbs: the interlocking chains of modern civilization. The American Dream of living in a suburb brought with it our daily dependence on oil and cars. Thus are individual, national and global decisions made; hundreds of millions of our individual lifestyle choices accumulate upwards into national policy, with vast impacts on global politics and the world’s ecosystem.

Eric Sanderson is the Senior Conservation Ecologist for the Wildlife Conservation Society at the Bronx Zoo, already noted for his natural history of New York City, the Welikia Project. [Sanderson is also an advisor to City Atlas.] In his new book Terra Nova: The New World After Oil, Cars, and Suburbs, Sanderson uses a range of fascinating diagrams, along with research in history, chemistry, biology, physics, and economics, to explain the bonds between oil, cars, suburbs, and the consequences of their hegemony over the American landscape. Sanderson then conjures a new world where the ruling triumvirate is replaced by renewable energy, streetcars, and high density cities.

Picture a suburban home. Many of us will imagine a large house surrounded with a little white fence, perfectly cut large lawns where you can easily fit another house, a long, paved path that leads to a garage and three cars: a SUV, a minivan, and a luxury sedan. Cars and a spacious house in the suburbs are the trademark images of the American Dream. Sanderson argues that these images have been so deeply embedded into American society that “many Americans began to think oil-cars-suburbs was the American Dream, confusing means with ends.”

The quest to inhabit the American Dream began with the mass adoption of cars and plentiful supplies of oil. Sanderson calls the years bracketed by 1931 and 1971 “the cheap oil window”; in inflation-adjusted dollars, gasoline never cost more than $3 per gallon and reached as low as $1.75 per gallon for the 40 years during which the modern landscape of America was created.

The low cost of gasoline encouraged the use of cars. Cars allowed people to escape crime and the poor sanitation of cities by moving into suburbs, but also allowed them to commute back into the city to work. Profits drove farms to sell their land to developers, and builders then constructed houses that people bought (and for which they then inherited years of debt, via their mortgages). Cheap oil and cheap real estate created suburbs out of rural land across the United States.

Sanderson points out that “these things – oil, cars, suburbs – are not monsters on their own, but only monsters as we have made them, and because of what they make us do.” And he itemizes the negatives, which go even beyond the primary environmental concerns. As an ecologist, Sanderson has a sharp eye for dysfunctional systems, and though the criticisms are familiar, to see them gathered makes an impression.

Between societies, oil “brings us hatred from the people who have the wells; wars in the Middle East to protect the supply.”

Within our own society, cars prevent engagement with others, discourage exercise, and add the background risk of fatal accidents. Suburbs lack variety, segregate, and also limit interactions with other people. Economically, oil causes “economic shocks, cycles of unemployment, inflation, and foreclosure.”

“Cars create congestion and waste people’s time in traffic, require more roads and repairs, and demand parking lots which are a waste of land use. Suburbs require large property taxes and demand more oil consumption. Environmentally, oil extraction and refining methods cause climate change and pollution. Cars use oil and thus also contribute to climate change and pollution, and heavily alters nature with the demand of roads. Suburbs buy out viable farmland which can lead to increases in food prices.

Sanderson envisions a new world where our dependence on oil, cars, and suburbs rapidly decreases. He uses a tool for understanding interconnected systems, the Muir Web, and proposes creating a positive feedback loop between energy, transportation, land use, and nature, creating benefits in the same way a healthy ecosystem functions.

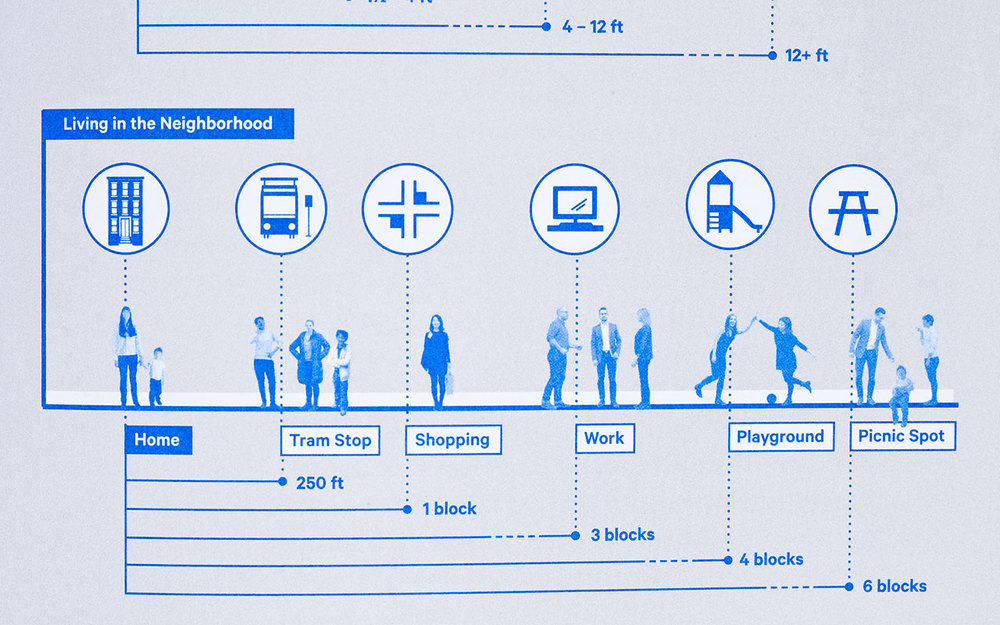

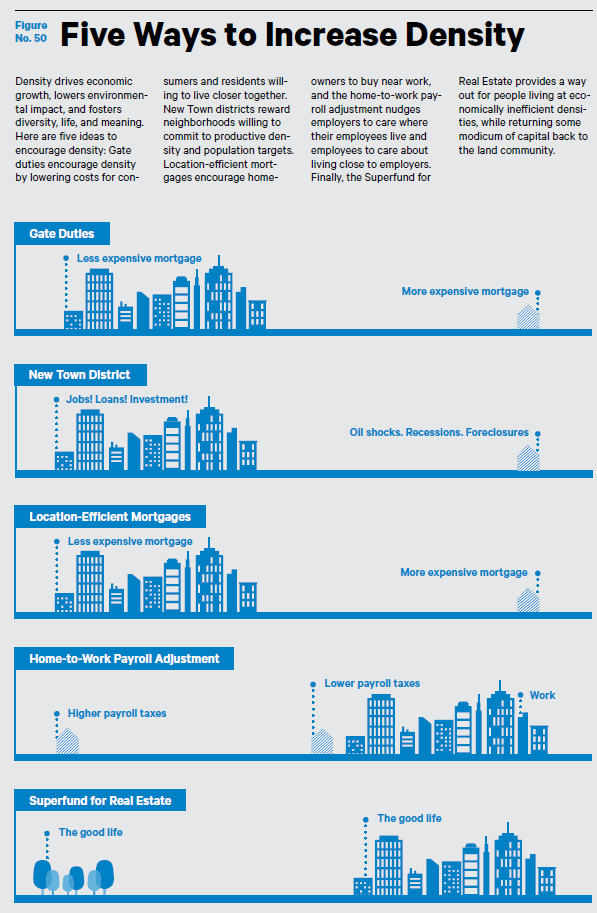

Humans are truly a node in the larger system. For our nation, and our globe, to flourish, we must preserve the systems we are dependent upon. Sanderson proposes that a positive feedback loop can be stimulated by the institution of “gate duties,” part of a taxing system that correctly prices the cost of using natural resources. Other prescriptions include encouraging greater population density, replacing roads with rails and cars with streetcars, and oil and gas with renewable energies such as wind and solar.

People will not be easily convinced to sacrifice their beautiful suburban homes and cars, and certainly politicians are in no rush to try. Sanderson does recognize the difficulty of what he is asking Americans to accomplish; “There will be cost and there will be sacrifice; evolution never occurs absent adversity.” These propositions require changes in lifestyles, but the land of the free and its inhabitants will surely put up a fight. The challenge is figuring out when the signals from nature become so pronounced that they are unmistakeable, and some would say that point is now.

Another writer, with more of a skeptical take, is David Owen, who asserts in his book The Conundrum that “what’s proven impossible, at least so far, is to commit to taking steps that would actually make a large, permanent difference on a global scale. Do we honestly care? That’s the conundrum.” Alternatively, the writer and thinker Stewart Brand is an optimist on the human capacity for change, as shown in his TED talk about the qualities of dense cities. All three authors, Owen, Brand, and Sanderson, agree that the best future for humans is provided by the social benefits and efficiency of urban living.

It’s been recently noted in the New York Times that change is afoot, and from an unexpected quarter. It turns out that interest in cars, and thus perhaps in suburbs, is in decline among young Americans. Smartphones have superseded wheels as the most important part of a young person’s life. Maybe the deep recognition of how much change is necessary is underway, already, below the radar. In the meantime, Eric Sanderson has built a powerful argument for a new design for America, one that can only get more appealing in the challenging years ahead.